At a crowded food stall, I once offered to pay for a few friends to keep the line moving, and it went sideways the moment the crowd hit. It worked for two minutes. Then the cashier’s system slowed, everyone behind us started pressing forward, and suddenly the “nice gesture” turned into a bottleneck. People weren’t angry at the food. They were angry that one person’s payment had become the only way the group could move. That’s the kind of failure fee sponsorship and alternate-token fee payment can trigger on Fogo during a rush.

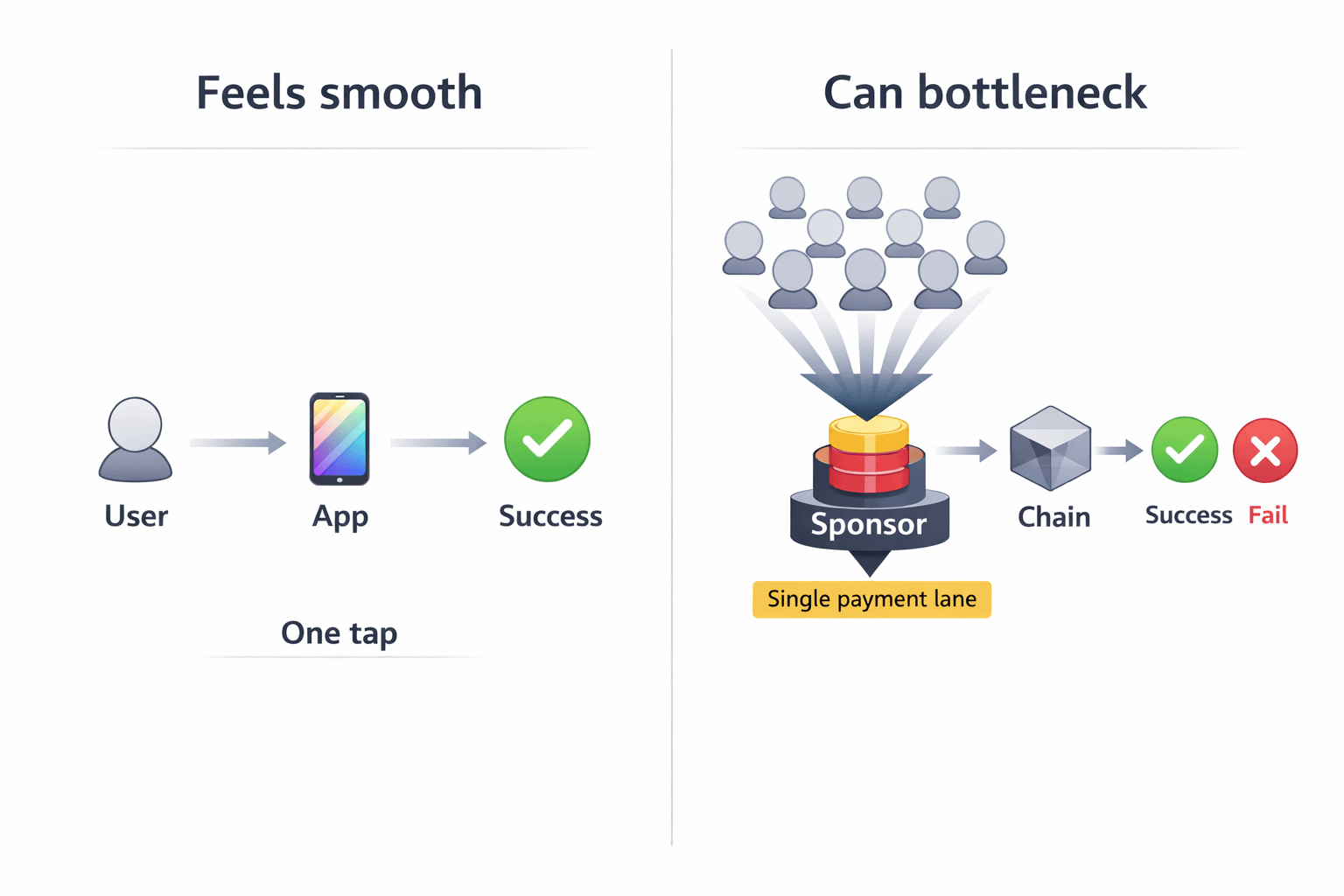

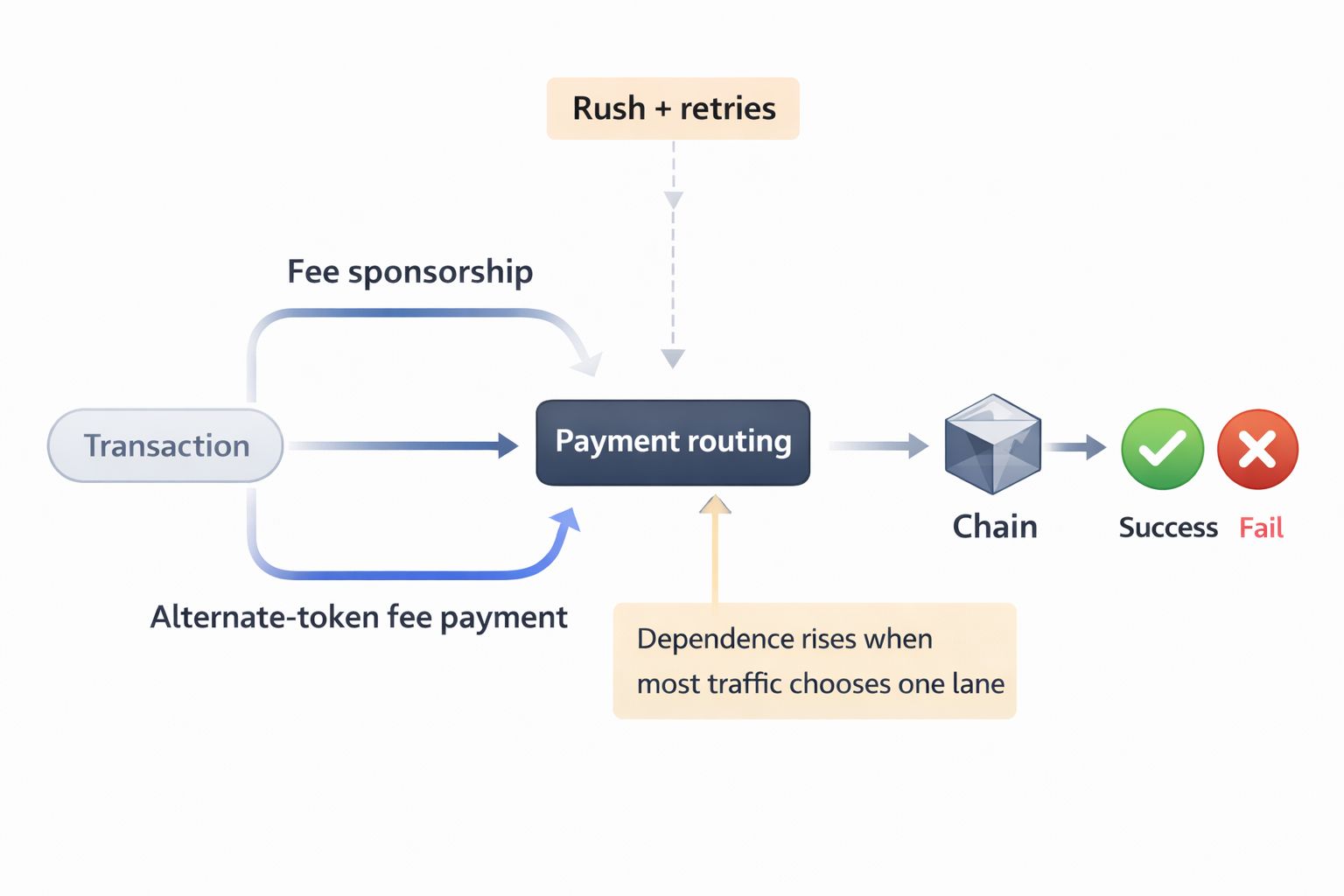

The mispriced belief is that gas abstraction is just UX sugar. It is not. It changes who is responsible for liveness at the user level. If a high-traffic app is paying fees on behalf of users, or letting users pay in something other than the native fee asset, you are moving the failure boundary. During calm periods it feels smooth. In peak minutes, it can become a single choke point. That’s the constraint. A rush is impatient and full of retries. A small slowdown turns into a resubmission wave. In that moment, anything centralized in practice, even if it is optional in theory, gets stress-tested hard.

Fogo’s promise is predictability under load, not just “fast when things are easy.” In that world, removing payment friction is not a cosmetic feature. It is a reliability wager. Fee sponsorship reduces the number of user decisions. Alternate-token fee payment reduces the number of user prerequisites. Together they can make onboarding feel like normal software. They also create a new question that users never ask out loud but always feel in their fingers: when everyone shows up at once, does the flow still work, or does it freeze because the payer path can’t handle the surge.

The sacrifice is straightforward even if people don’t like admitting it. If sponsored usage concentrates, you give up fee-payer decentralization. More activity routes through fewer payers. That can be acceptable if the result is fewer failed actions for normal users. It becomes unacceptable if the concentration turns into fragility. The worst case is not “fees are a bit higher.” The worst case is “the app looks alive but nothing goes through,” because the sponsor path becomes saturated, limited, drained, or simply mismanaged.

I’m not talking about villains. I’m talking about basic systems behavior. If a single payer is covering a large share of peak activity, that payer becomes an operational dependency you can see in sponsored transaction share and in burst-time shifts in the fee-payment token mix. It has to be funded, online, and responsive through the entire rush. If it falls behind, everyone routed through that lane stalls at once, which is exactly what concentration signals are warning you about.

Alternate-token fee payment adds another layer. It can be great because users hate juggling the “right” token just to click a button. But it also means the chain is now carrying a mix of fee payment assets during busy windows. If that mix shifts sharply under stress, it is a signal that behavior is changing. Users and apps are reacting. Some are trying to buy reliability by switching what they pay with. Some are trying to avoid friction by staying inside a sponsored route. This is where the proof surface becomes visible in a way that doesn’t require guesswork: the burst-time shift in the fee-payment token mix and the sponsored transaction share.

If you want a simple mental model, think of a bridge with two lanes. One lane is users paying directly. The other lane is sponsored flow or alternate-token flow. In normal traffic, both lanes move. In a surge, one lane can become the crowd’s default, because it feels easier. That is exactly when you learn whether the lane is built for load or built for demos. If it is built for demos, the lane becomes a parking lot and the whole bridge feels closed.

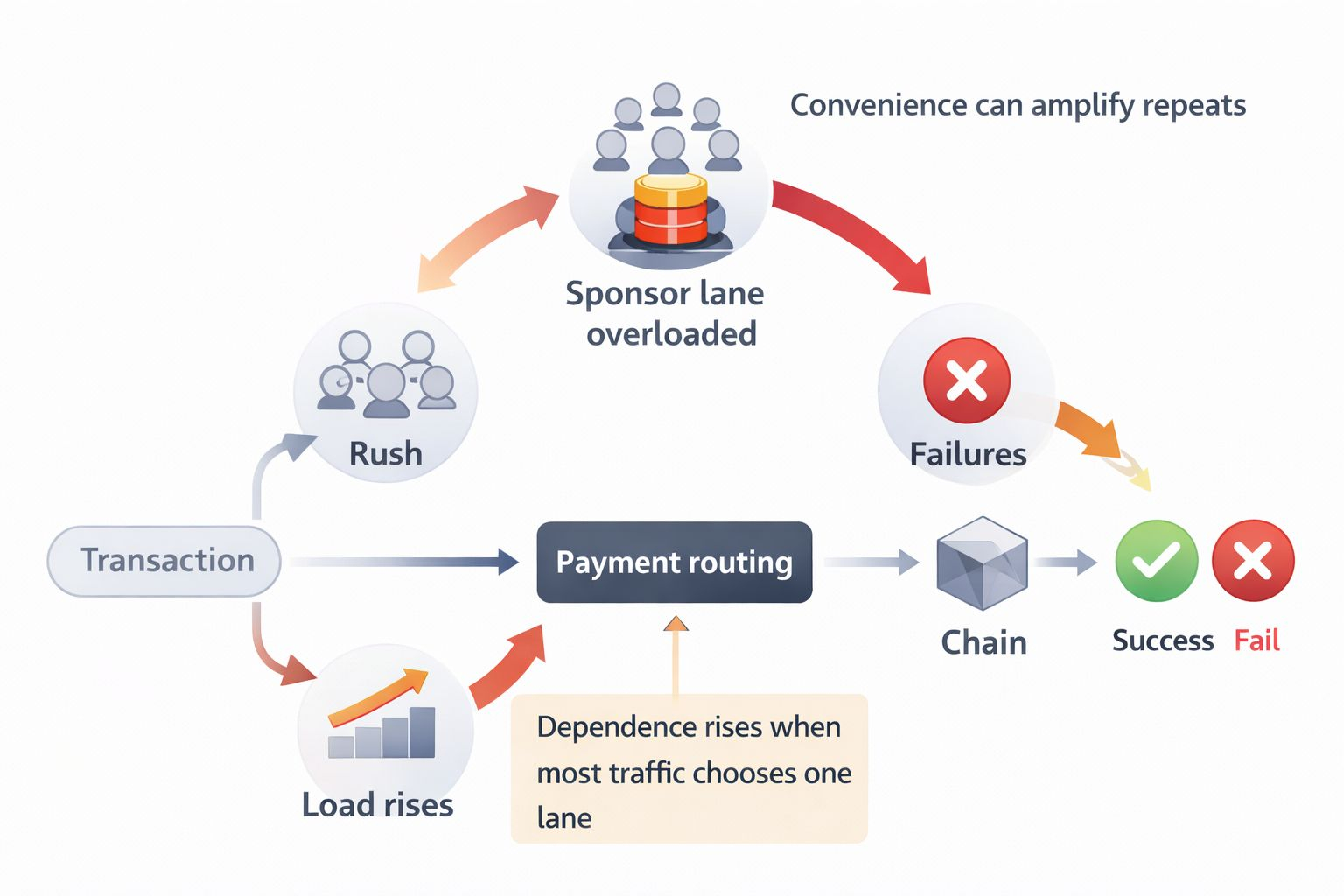

The failure mode I worry about is not a dramatic “hack.” It is a boring collapse. Sponsored usage concentrates because it is convenient. The sponsor path hits limits during a surge. Users start seeing failures. They retry. The retries increase load on the same path. Failures rise again. The chain might still be producing blocks and processing other activity, but the mainstream user experience becomes “it doesn’t work.” That kind of experience creates churn fast.

There’s also a second failure shape that looks more subtle but harms trust even faster. When payment becomes abstracted, users stop learning how the system works. They stop thinking about fee conditions. They stop noticing when the environment changes. That is a good thing when the system is stable. It is a bad thing when the system becomes unstable, because users have no instincts for recovery. They don’t know when to wait or when to stop retrying. They just keep tapping. The app looks broken, and the chain gets blamed even if the underlying issue is payment routing.

A chain built for consumer use has to assume people will behave like consumers. They will retry fast. They will open and close the app. They will switch networks. They will blame the product, not the infrastructure. If you take away the friction, you also take away the pause that sometimes prevents runaway retries. That means the payment design has to be resilient enough that convenience does not turn into a retry amplifier.

A realistic surge scenario is easy to picture. A consumer app suddenly gets attention. Thousands of users try the same action in a short window. The app uses fee sponsorship to make onboarding smooth. For the first wave, it feels magical. Then the sponsor path becomes the default for almost everyone. The chain isn’t necessarily congested in a global sense, but the sponsor dependency is. Failed actions start appearing in clusters. Users hit retry. Support chats fill. People start posting screenshots of failures, not fees.

At that point, it doesn’t matter how strong the rest of the stack is. The user experience has narrowed to one question: can the sponsor route keep up under pressure. If it can’t, a healthy base system can still feel broken to users during peak minutes because the sponsored lane is failing them.

Over time, my way of judging this isn’t complicated. I would watch peak minutes and look for two linked behaviors. First, does the sponsored transaction share rise sharply, and does it stay healthy. Second, when the fee-payment token mix shifts, does it correlate with stability or with failures. If both signals move but failures stay stable, the abstraction layer is doing its job. If the signals move and failures rise with them, it means the convenience lane is collapsing exactly when it is supposed to carry the crowd.

This is also where builders need to be honest with themselves. If your app depends on sponsorship to feel normal, you must treat sponsorship like production infrastructure, not like a marketing feature. It needs budgets, monitoring, and failure planning. If you rely on alternate-token fee payment to reduce onboarding friction, you need to understand how it behaves under congestion and how users will react when one payment route becomes “the way” during rushes.

I don’t think mainstream users will judge Fogo on a calm day. They will judge it during the first time their friend sends them a link and says “try this,” and the app either works smoothly or fails twice and gets deleted. In that moment, gas abstraction isn’t sugar. It’s the difference between adoption and churn.

If, during peak minutes, sponsored-tx share rises while sponsored-tx failure rate also rises, then fee sponsorship plus alternate-token fee payment is concentrating load into a choke point instead of making onboarding reliably smooth.