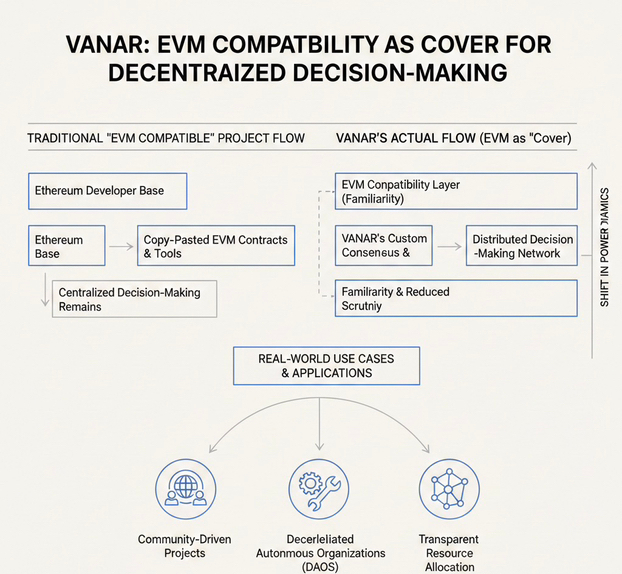

If you’ve been around this market long enough, you develop a reflex: whenever a project says “EVM compatible,” you assume it’s a routing move. A way to borrow the Ethereum developer base, copy-paste contracts, and look familiar enough that people stop asking hard questions. Most of the time, that instinct is right.

Vanar gets more interesting when you stop treating “EVM compatibility” as the story and start treating it as cover—cover for what it’s actually trying to sell: a different place for decision-making to live.

Because the real friction in crypto products isn’t that the chain can’t execute transactions. The friction is that the parts that make an app feel reliable—the checks, the permissions, the “is this allowed,” the “is this valid,” the “do we settle this or hold it”—almost always end up off-chain. Not because teams love centralization, but because they need judgment, context, and audit trails, and most chains don’t carry context well.

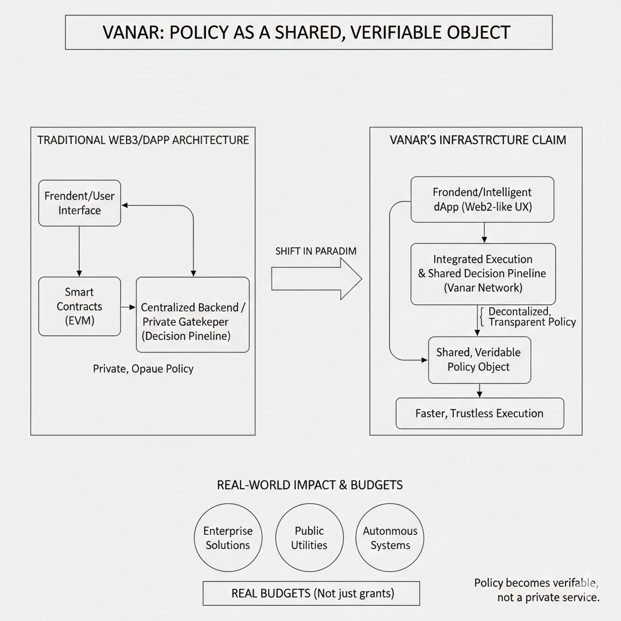

So what happens in practice is predictable. The chain becomes the final receipt printer. The intelligence lives in a server somewhere: risk scoring, compliance gating, document verification, limits, exceptions, overrides. Then the app pushes a cleaned-up transaction on-chain after the real decision already happened in private. Users think they’re using a decentralized product; operators know the truth: the chain is downstream from the actual control panel.

Vanar’s Kayon + Neutron framing reads like a push against that pattern. Not in an ideological way. In a “this is where money actually gets made” way.

Here’s the simplest way to say it without dressing it up: Vanar wants contracts to stop being dumb vending machines. It wants them to be able to reference structured context and enforce rules that normally require a backend team.

Neutron is the quiet part of that pitch. Most “smart” flows break because the inputs are messy. Policies live in documents. Proofs live in files. Media, invoices, identity artifacts, statements—whatever you’re gating on—doesn’t fit neatly into a contract’s world. Vanar’s idea is to take that stuff, compress it, structure it, and turn it into on-chain-friendly objects they call Seeds. If that works, it’s not glamorous, but it’s critical. You don’t get smarter execution by shouting “AI.” You get it by making the input space small enough and clean enough that logic can actually operate on it.

Then Kayon is supposed to sit on top of that. The project describes it as an on-chain reasoning engine—language aside, the point is that it’s meant to evaluate conditions and trigger actions based on verifiable, structured data, without the usual “call the server / query the oracle / run the keeper” stack doing all the real thinking in the background.

Now, if you’re thinking like an operator instead of a tourist, the immediate question isn’t “is that cool.” The question is: what does this replace?

And the replacement target is obvious: the private rules engine every serious app ends up building.

Payments are a good example because they force honesty. In real payment rails, you don’t settle first and ask questions later. You check first. You screen. You enforce limits. You validate eligibility. You decide whether the flow is permitted under whatever constraints you live under. Those systems are expensive and brittle, and they’re where institutions hide their real IP. The chain isn’t the hard part. The rules are the hard part.

Vanar keeps hinting at that world—validate compliance before payment flows, not after—and that detail matters more than any headline feature. Because it signals what they think the market is actually buying: not throughput, but policy latency. How quickly and cleanly you can make a defensible decision.

That’s also why the EVM part matters. If you’re trying to convince builders to move their rules closer to execution, you don’t get to also make them learn a brand-new environment, new tooling, new audit patterns. “EVM-compatible” isn’t the differentiation; it’s the on-ramp. It’s how you get teams through the door without burning months rewriting their stack. Vanar’s own materials are explicit about this “what works on Ethereum works on Vanar” approach. And the codebase lineage points to a Geth-rooted, Ethereum-style client foundation. That tells you they’re betting on familiarity where it counts.

But familiarity cuts both ways. The EVM ecosystem has a habit: when something is hard to do on-chain, teams quietly move it off-chain. Admin keys. Private services. Centralized allowlists. Opaque risk checks. It’s practical. It ships. It also means the “decentralized” part ends up being the least important part of the product.

So the real test for Vanar is not whether Kayon exists. It’s whether it changes behavior.

Do builders actually stop reaching for the server as the default escape hatch?

Do they use Neutron-like structured artifacts as inputs to enforceable logic?

Do counterparties trust outcomes because they can verify the path, not because they trust the operator?

Because there’s an uncomfortable truth here: anything that touches compliance, identity, or risk eventually gets interrogated. Someone asks why a payment was blocked. Why an account was approved. Why an exception was granted. If your “intelligence” can’t be explained, it becomes a liability. If it can be overridden without trace, it becomes a backdoor. In regulated workflows, the winner isn’t the system that looks smartest. It’s the system that can produce an answer under scrutiny.

That’s where Vanar’s pitch either becomes powerful or collapses.

If Kayon is mostly deterministic reasoning over verifiable Seeds, you get something operators actually want: a decision layer you can audit and settle. If Kayon leans on probabilistic inference in the critical path, you might get a smoother UX, but you also inherit the hardest problem in financial systems: explainability. And explainability isn’t a philosophical nice-to-have. It’s what keeps your product alive when the first serious counterparty asks questions.

So when I read “Vanar makes intelligent dApps feel like Web2,” I don’t interpret it as UX marketing. I interpret it as an infrastructure claim: that you can build apps where the decision pipeline is close enough to execution that you don’t need a private gatekeeper for everything.

If that’s true, Vanar isn’t trying to be “another chain.” It’s trying to be the place where policy becomes a shared, verifiable object instead of a private service. That’s a lane most projects avoid because it’s harder to demo and slower to prove. But it’s also the lane where budgets exist. Real budgets. Not “developer grants” budgets.

And if it’s not true—if teams still end up rebuilding the same off-chain rule engines, still relying on private logs and discretionary backends—then Vanar’s differentiation thins out fast, and you’re back in the generic arena where ecosystems are rented and narratives rotate.