Did you think that string of UUID written in the code was just a handshake signal to connect to the server?

On December 16, 2025, it became a backdoor to the treasury.

A quantitative team called AlphaQuant hardcoded the API authentication UUID of the production environment into the frontend code to connect to APRO's Data Pull service, and carelessly pushed it to a public GitHub repository. A few hours later, a scanning script detected this 'free lunch', and hackers made twenty million malicious requests within 3 hours, not only draining their preloaded quota but also emptying the cold wallet of 123,000 USDC due to the 'auto-recharge' feature being enabled.

The real nightmare was yet to come—the money was gone, and the problem became:

Who should bear the cost of this? Is it the loss of the "attacked party," or the result of "normal billing"?

Faced with APRO's contractual terms and on-chain evidence, this incident quickly escalated from an engineering problem into a vivid lesson on "legal liability for API keys."

How can a UUID become a $123,000 time bomb?

First, explain the technical background clearly.

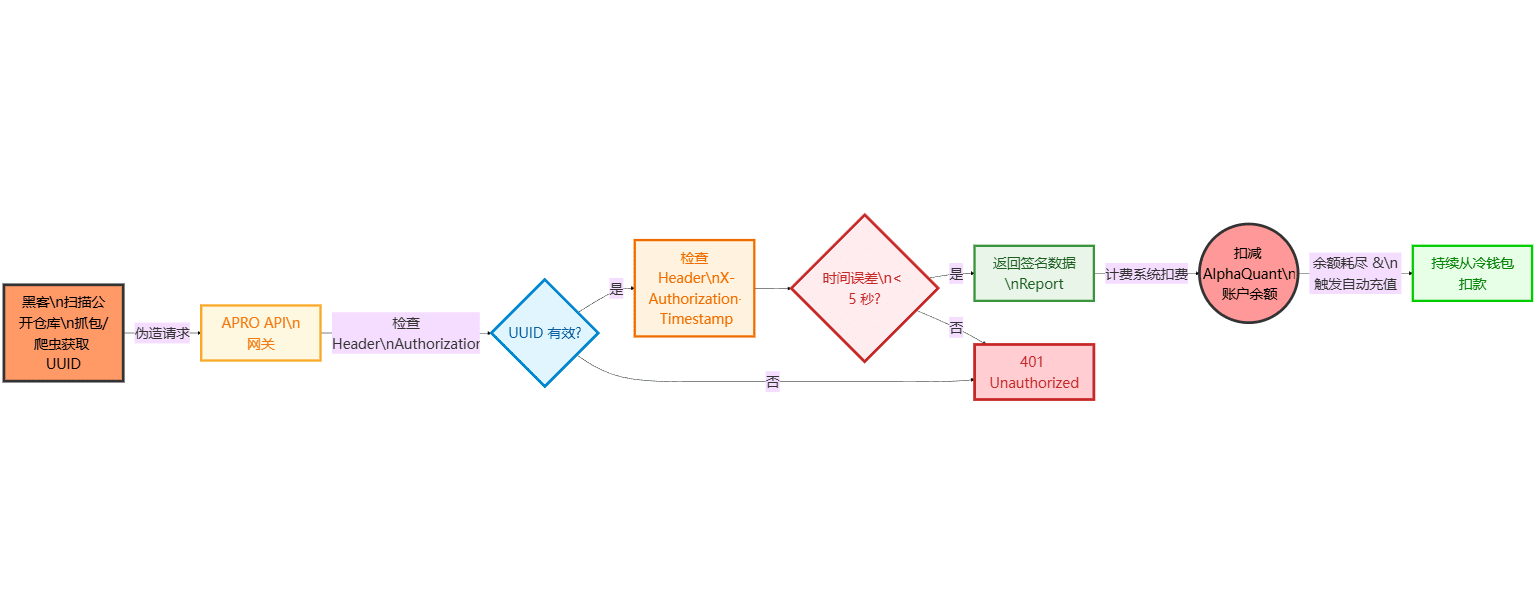

APRO's Data Pull model is a standard "off-chain on-demand data pull":

You use the Authorization: <UUID> marker to indicate "who I am";

In addition, include the X-Authorization-Timestamp; the time error must be less than 5 seconds.

Once the server verifies the transaction, it will return a signature report and deduct the fee from your prepaid balance per transaction.

From an economic model perspective, this UUID is your billing identity:

Each valid request corresponds to a service fee payable.

As long as the request header is valid, APRO has the contractual legitimacy to "receive money and provide services".

The problem is: once the UUID is leaked, attackers can "generate a table for you like crazy"—

You may not necessarily lose data, but you are definitely burning through money like crazy.

More importantly, APRO's terms of use explicitly state the responsibility for the safekeeping of such authentication credentials:

The user is fully responsible for any calls and charges incurred due to the leakage of credentials, which shall be considered as the user's actions.

In other words, from a legal perspective, this is not "APRO being overwhelmed," but rather:

Your "key" was used to max out your credit card.

The gateway is simply "deducting fees normally according to the rules".

Attack path: From a GitHub repository to 20 million malicious requests

The technical approach used in this attack was actually brutally simple:

The accident reconstruction roughly follows this timeline:

02:00

An intern at AlphaQuant, in order to "facilitate debugging," pushed the configuration file with the production UUID to a public repository on GitHub.02:xx

The automated script begins scanning newly submitted code, identifying strings with a format similar to Authorization: xxxxx-xxxxx-..., and marking them as "suspicious credentials".03:00 – 06:00

A hacker script locked APRO's GET /api/v1/reports/latest interface.Generate valid timestamps in real time;

Forged request headers to resemble AlphaQuant;

The system initiates calls at a millisecond frequency, with a cumulative request volume exceeding 20 million times.

Because AlphaQuant has "automatic top-up" enabled:

Account balance depleted → The system will automatically deduct from the linked cold wallet;

A few hours of no human intervention eventually resulted in a funding hole of 123,000 USDC.

When the operations team opened the Dashboard at 8 a.m., they only saw a string of cold, hard numbers:

The balance is zero, the quota is exhausted, and the nighttime call volume curve is vertically full.

Who should pay the price? APRO believes this is a contractual issue, not an accident.

Intuitively, many people would categorize this as a "hacking attack".

However, from the perspective of APRO's legal and billing systems, this is almost a "perfectly compliant" use case:

The UUID in the request header is valid;

The timestamp is perfectly valid and meets the <5-second window requirement;

The API path being called is within the agreed service scope;

The billing rules are also strictly implemented in accordance with the agreement.

AlphaQuant subsequently attempted to claim compensation from APRO, arguing that:

"The system failed to detect abnormal traffic, which should be considered a service vulnerability."

APRO's response was very Web3-like:

The contract terms are clearly stated:

The user is responsible for keeping the credentials confidential.

The system is only responsible for whether the "credential is valid and the request format is compliant";

From a financial perspective:

APRO provides data services for the corresponding number of times;

The call behavior conforms to the authentication logic and there is no "unauthorized access".

The result is a cold, hard reality:

In the on-chain world, API Keys are also "assets".

The loss was due to poor asset management, not a service dispute.

From an industry perspective, the precedent set by this case is more important than the amount of loss.

It has essentially established a consensus:

Under the pull model, the application itself bears the risk of application code failure.

What can developers do? Five lines of defense that need to be added now.

From a developer's perspective, the key lesson from this incident is not that "APRO is too cold-blooded," but rather:

You've put the money-spending switch in a place where anyone can press it.

If you are currently working on or preparing to integrate with a pull-type API like APRO, the following five lines of defense are the foundation that should be implemented now:

① The key will never be sent to the front end or to a public repository.

All API Keys/UUIDs must be stored in server-side environment variables or a key management service;

The front-end only interacts with its own back-end, which then calls APRO.

The presence of plaintext keys in a Git repository should be considered a "major security incident".

② One environment, one key; one purpose, one limit

Production, testing, and development environments each use different API keys that are not reused.

Split sub-keys for different services and set different QPS/daily limits;

Even if a key is leaked, it will only burn through a portion of the budget.

③ Always turn off "unlimited automatic top-up" and set a spending limit for each Key.

Treat "automatic recharge" as an emergency button for production accidents, rather than as the default setting;

Set a daily/hourly spending limit for a single key; if the limit is exceeded, the key will be automatically disabled and a notification will be sent.

Integrate Telegram Bot/email alerts so that at least someone will be woken up if something happens at night.

④ Make good use of IP whitelists and network boundaries

Try to allow only requests from specific IPs and specific VPCs to access APRO;

For high-value keys, bind them to a dedicated server exit point and prohibit direct connections from the local development environment;

Rotate keys regularly, and consider "not changing them for a long time" as a risk item.

⑤ Incorporate the concept of "API Key = Private Key" into internal regulations.

The legal and technical teams went through the terms of service together and clarified:

Key leak → Who is responsible?

Can you purchase cybersecurity insurance/professional liability insurance to cover this type of risk?

New employees should receive security training, and there should be clear consequences for any action that pushes a production key to GitHub.

APRO subsequently implemented features such as IP whitelisting and daily spending limits, which can mitigate the severity of similar incidents. However, the root cause remains the same old problem:

No matter how high the external firewall is, you are the one who turns on the gas.

Pull vs Push: Security Boundaries Are Migrating from On-Chain to Code Repository

There is another easily overlooked background to this event: the change in the oracle interaction model.

Traditional Push Model (On-Chain Broadcast):

Prices and data are actively uploaded to the blockchain by nodes, and everyone passively reads them;

Data is a public good; there is no such thing as a "pay-per-use" API key.

The key to security lies in the node itself (whether the price feed is fraudulent).

Pull Model (Pull on Demand):

Data is billed per call, with the API Key serving as the "unit of measurement".

The security boundary extends to the application code of every interfacing party;

Any mistake in key management on either side could directly result in financial loss.

APRO, Kite, and an increasing number of Oracle 3.0 / Off-chain Compute projects essentially move some of their business logic from the blockchain to the "API as a payment gateway" model.

This greatly improves flexibility:

You can customize the frequency, granularity, and data type;

There is no need to pay for the broadcast costs for all users across the network.

But the cost is also clear:

You are no longer just using a wallet that "reads the chain".

Instead, they are operating a "money-burning" app account.

From a regulatory perspective, organizations like VARA have begun to include these types of API security incidents within the scope of "critical infrastructure operational risks," requiring service providers to conduct at least basic security training for institutional users before issuing keys. This isn't meddling; it's the entire industry catching up on its shortcomings.

In summary: API Keys are the private keys of the new era.

After FTX, we learned:

You shouldn't put all your coins on centralized exchanges;

Don't just look at the balance on the UI; learn to look at the on-chain address.

APRO x SolvBTC's PoR tells us:

The security of assets requires proof using code and cryptography.

This UUID leak from AlphaQuant adds the third lesson:

In the Off-chain era, API Key itself is already a "directly convertible asset".

It doesn't grow in your wallet, it grows in:

In your .env file;

In your CI/CD configuration;

In your Git commit history.

Before the next wave of machine economy boom, whoever engraves this into their team's DNA first will avoid paying a $123,000 "tuition fee".

I'm like someone who tries to find a lost sword by marking the boat; after writing this, I suggest you do one thing:

Back in my repository, I searched for the API_KEY, UUID, and Authorization.

If you've found anything by now, this article has already earned you your first unseen benefit.@APRO Oracle #APRO $AT