I realized something was off the day a game congratulated me for winning without me feeling anything. I was standing in line at a coffee shop, phone in one hand, cup in the other, half-playing a mobile game I’d installed months earlier. The screen flashed rewards, progress bars filled themselves, and a cheerful animation told me I’d “outperformed expectations.” I hadn’t learned a mechanic. I hadn’t taken a risk. I hadn’t even decided much. The system had decided for me, smoothing every edge so I wouldn’t leave. When I closed the app, I couldn’t remember what I’d actually done—only that the app seemed very pleased with me.

That was the moment I noticed the contradiction. The game claimed to optimize fun, engagement, and satisfaction, yet the more perfectly it anticipated my behavior, the less present I felt. It was efficient, polite, and empty. I wasn’t bored in the traditional sense; I was anesthetized. The system was doing its job, but something human had quietly slipped out of the loop.

I started thinking of it like an airport moving walkway. At first, it feels helpful. You’re moving faster with less effort. But the longer you stay on it, the more walking feels unnecessary. Eventually, stepping off feels awkward. Games optimized by AI engagement systems behave like that walkway. They don’t stop you from playing; they remove the need to choose how to play. Momentum replaces intention. Friction is treated as a defect. The player is carried forward, not forward-looking.

This isn’t unique to games. Recommendation engines in streaming platforms do the same thing. They don’t ask what you want; they infer what will keep you from leaving. Banking apps optimize flows so aggressively that financial decisions feel like taps rather than commitments. Even education platforms now auto-adjust difficulty to keep “retention curves” smooth. The underlying logic is consistent: remove uncertainty, reduce drop-off, flatten variance. The result is systems that behave impeccably while hollowing out the experience they claim to serve.

The reason this keeps happening isn’t malice or laziness. It’s measurement. Institutions optimize what they can measure, and AI systems are very good at optimizing measurable proxies. In games, “fun” becomes session length, return frequency, or monetization efficiency. Player agency is messy and non-linear; engagement metrics are clean. Once AI models are trained on those metrics, they begin to treat unpredictability as noise. Risk becomes something to manage, not something to offer.

There’s also a structural incentive problem. Large studios and platforms operate under portfolio logic. They don’t need one meaningful game; they need predictable performance across many titles. AI-driven tuning systems make that possible. They smooth out player behavior the way financial derivatives smooth revenue. The cost is subtle: games stop being places where players surprise the system and become places where the system pre-empts the player.

I kept circling back to a question that felt uncomfortable: if a game always knows what I’ll enjoy next, when does it stop being play and start being consumption? Play, at least in its older sense, involved testing boundaries—sometimes failing, sometimes quitting, sometimes breaking the toy. An AI optimized for engagement can’t allow that. It must close loops, not open them.

This is where I eventually encountered Vanar, though not as a promise or solution. What caught my attention wasn’t marketing language but an architectural stance. Vanar treats games less like content funnels and more like stateful systems where outcomes are not entirely legible to the optimizer. Its design choices—on-chain state, composable game logic, and tokenized economic layers—introduce constraints that AI-driven engagement systems usually avoid.

The token mechanics are especially revealing. In many AI-optimized games, rewards are soft and reversible: XP curves can be tweaked, drop rates adjusted, currencies inflated without consequence. On Vanar, tokens represent real, persistent value across the system. That makes excessive optimization risky. If an AI smooths away challenge too aggressively, it doesn’t just affect retention; it distorts an economy players can exit and re-enter on their own terms. Optimization stops being a free lunch.

This doesn’t magically restore agency. It introduces new tensions. Persistent tokens invite speculation. Open systems attract actors who are optimizing for extraction, not play. AI doesn’t disappear; it just moves to different layers—strategy, market behavior, guild coordination. Vanar doesn’t eliminate the moving walkway; it shortens it and exposes the motor underneath. Players can see when the system is nudging them, and sometimes they can resist it. Sometimes they can’t.

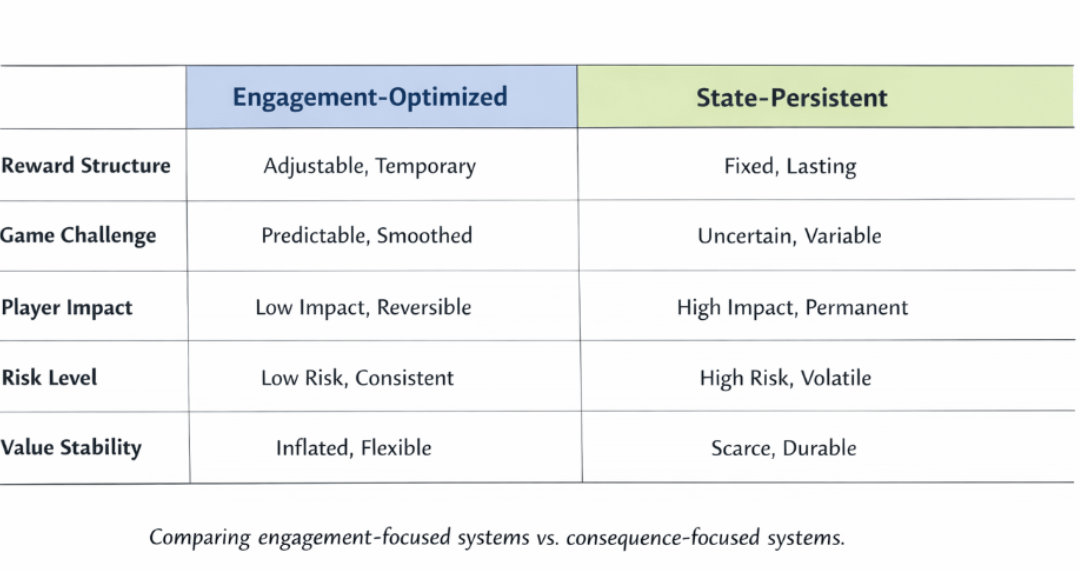

One visual that helped me think this through is a simple table comparing “engagement-optimized loops” and “state-persistent loops.” The table isn’t about better or worse; it shows trade-offs. Engagement loops maximize smoothness and predictability. Persistent loops preserve consequence and memory. AI performs brilliantly in the first column and awkwardly in the second. That awkwardness may be the point.

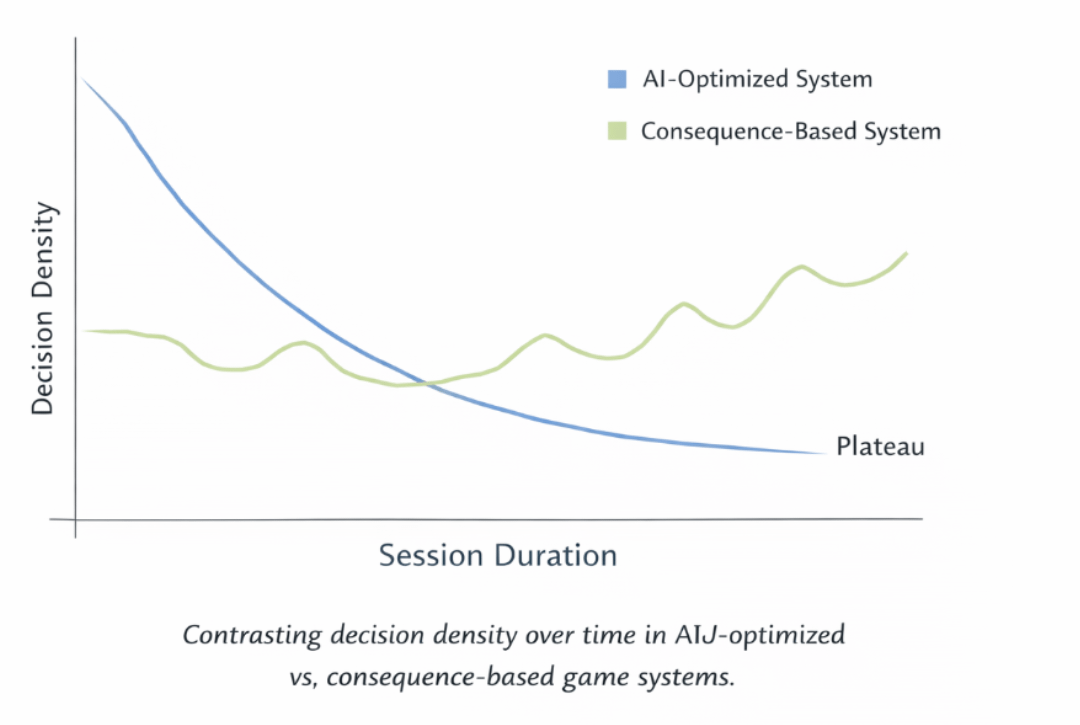

Another useful visual is a timeline of player-system interaction across a session. In traditional AI-optimized games, decision density decreases over time as the system learns the player. In a Vanar-style architecture, decision density fluctuates. The system can’t fully pre-solve outcomes without affecting shared state. The player remains partially opaque. That opacity creates frustration—but also meaning.

I don’t think the question is whether AI should be in games. It already is, and it’s not leaving. The more unsettling question is whether we’re comfortable letting optimization quietly redefine what play means. If fun becomes something inferred rather than discovered, then players stop being participants and start being datasets with avatars.

What I’m still unsure about is whether introducing economic and architectural friction genuinely protects play, or whether it just shifts optimization to a more complex layer. If AI learns to optimize token economies the way it optimized engagement metrics, do we end up in the same place, just with better graphs and higher stakes? Or does the presence of real consequence force a kind of restraint that engagement systems never had to learn?

I don’t have a clean answer. I just know that the day a game celebrated me for nothing was the day I stopped trusting systems that claim to optimize fun. If AI is going to shape play, the unresolved tension is this: who, exactly, is the game being optimized for—the player inside the world, or the system watching from above?