Gold is having a moment. Prices are up, the rhetoric is louder, and the usual suspects are dusting off familiar arguments about the end of fiat money. But beneath the noise, one crucial question matters more than all the rest: who is actually buying the gold?

What’s Supposed to Be Happening

The bullish narrative is well rehearsed. Global central banks, alarmed by geopolitical fracture and the weaponisation of financial systems, are supposedly shifting reserves out of dollars and into gold.

Ray Dalio, speaking at Davos last week, put it in apocalyptic terms. Countries fear their foreign assets could be frozen. Interdependencies are fraying. Great conflicts are emerging. Central banks, acting as they always have in moments of systemic stress, are rebuilding gold reserves. To Dalio, this is not just about the US dollar — it’s the beginning of the end for the entire fiat monetary order.

It’s a powerful story. Unfortunately, it’s also one that currently lacks hard evidence.

Why the Data Tells a More Complicated Story

Tracking central bank gold buying is notoriously difficult. Unlike ETF flows — which offer near-real-time visibility into retail demand — sovereign purchases arrive late and selectively.

Central banks report reserve data to the IMF through Article IV consultations, often with delays of up to six months. To get a timelier signal, analysts turn to a workaround: UK non-monetary gold exports.

London is the world’s dominant gold trading hub. When gold leaves the UK, it often ends up in central bank vaults. Historically, these export figures line up reasonably well with official data released later.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, central bank gold buying did indeed surge, roughly doubling to more than 1,000 tonnes a year. That part of the story is real.

What’s changed is the direction — and momentum — of that flow.

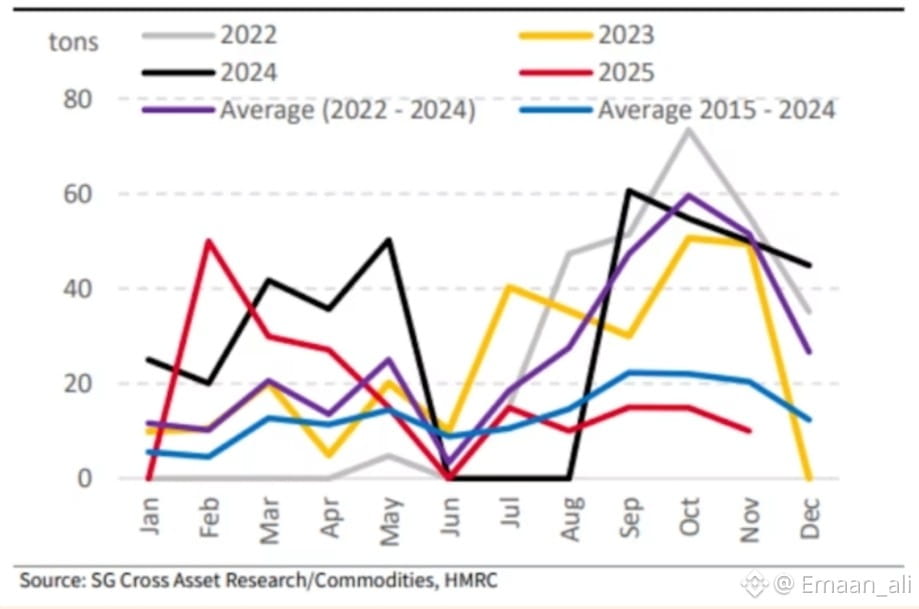

Adjusted for price, UK gold exports have been in steady decline for roughly a year. In November, exports by weight were down more than 80 per cent year-on-year. For a trade supposedly accelerating, that’s an uncomfortable data point.

Who’s Actually Buying?

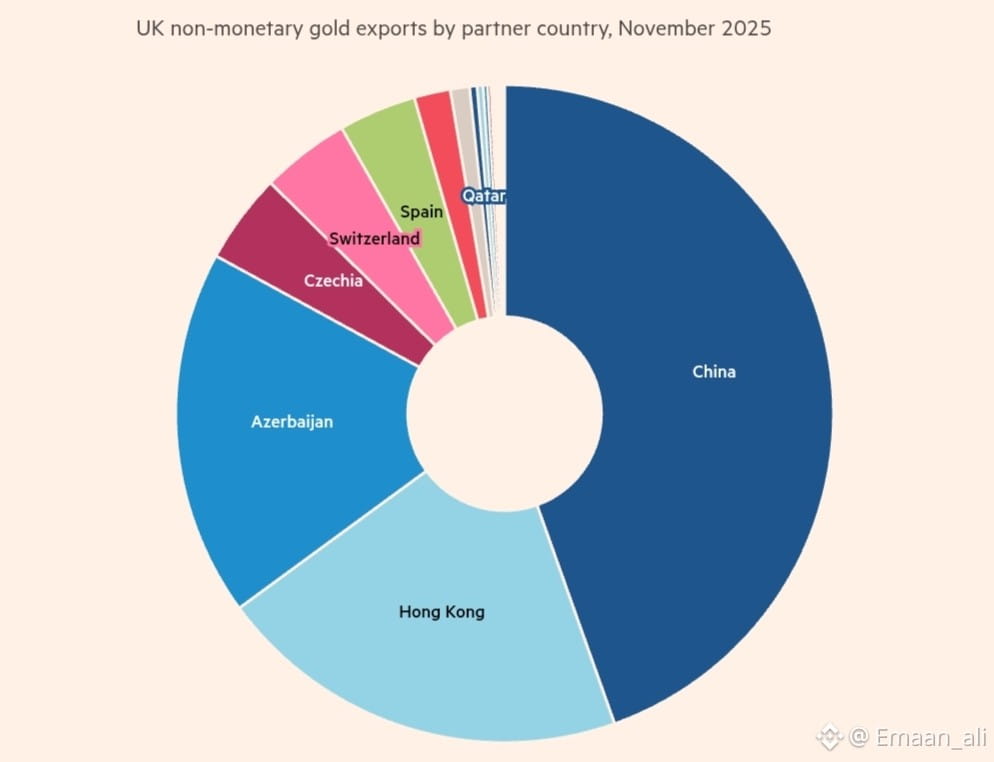

HMRC’s country-level export data adds more colour — and more doubt.

China remains the headline buyer. As of December 2025, it officially held more than 2,300 tonnes of gold, around 8.5 per cent of total reserves, following 14 consecutive months of reported purchases. UK export data suggests China may have bought even more than the People’s Bank of China has acknowledged.

But here’s the catch: the implied Chinese imports from the UK in November were under 10 tonnes, well below both recent and long-term averages.

That slowdown matters. If China were truly pursuing a structural shift — say, pushing gold to 20 per cent of reserves — it would require sustained purchases of roughly 33 tonnes per month for almost eight years. The latest data simply doesn’t support that trajectory.

Elsewhere, the picture is similar. Morgan Stanley analysts recently noted that central banks often target gold as a percentage of total reserves. When prices rise, the need to buy naturally falls.

Poland complicates the picture. Despite soaring prices, its central bank has approved plans to add 150 tonnes, shifting from a percentage-based target to an absolute tonnage goal. That signals intent but the UK export data for November shows Poland importing a vanishingly small 0.00002 tonnes.

Ambition, it seems, is running ahead of execution.

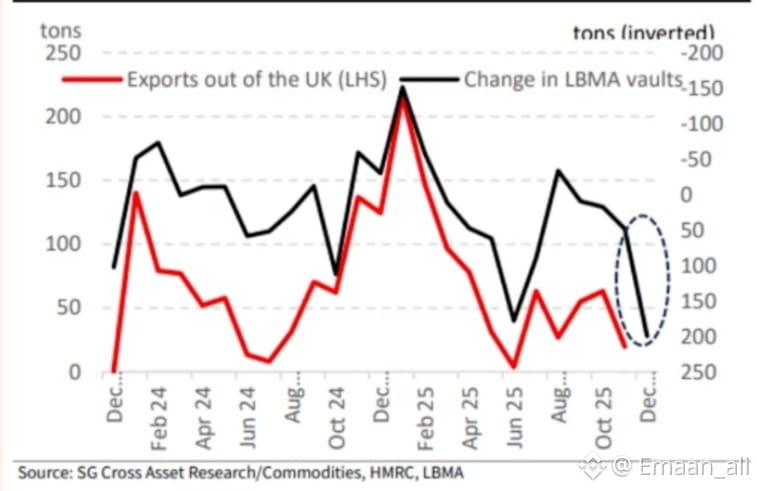

What the Vaults Are Saying

For a second opinion, analysts also monitor London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) vault holdings, released shortly after month-end.

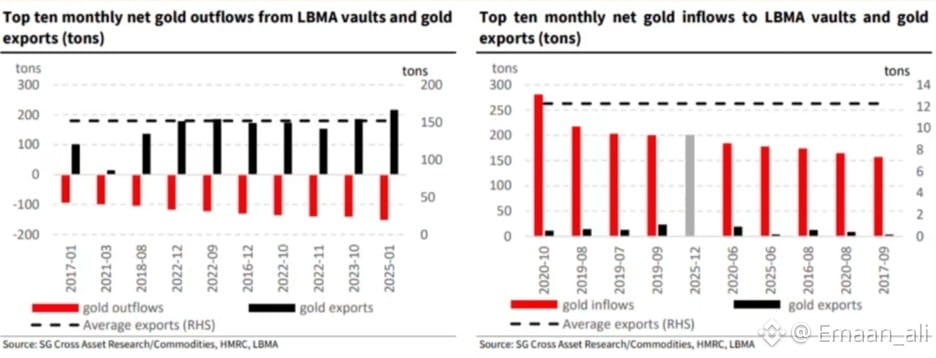

December’s data showed a striking 199-tonne increase in gold held in LBMA vaults. Historically, such buildups coincide with very low export activity — sometimes as little as 4 tonnes in a month implying minimal central bank buying.

When gold piles up in London vaults, exports — their proxy for sovereign demand are weak, averaging just 12 tonnes.

When vault holdings fall, exports surge, averaging more than 150 tonnes.

December fits squarely into the former camp.

What Happens Next

Taken together, the data suggests that the great sovereign rebalancing trade may have lost momentum, at least for now.

That doesn’t mean central banks are dumping gold. It means the pace of accumulation appears to be slowing — just as prices have accelerated. As Rob Armstrong argues, momentum-chasing, not reserve diversification, increasingly looks like the cleanest explanation for gold’s recent strength.

Whether this wave of gold enthusiasm is rational is a separate question entirely. Like most belief systems built on impending collapse, it inspires fierce conviction — and little patience for counter-evidence. As with all forms of financial fundamentalism, we’ll quietly decline the theological debate.

If central bank buying is slowing, what’s really driving gold higher — and how long can momentum alone sustain the rally?

#GoldOnTheRise #FedHoldsRates #TokenizedSilverSurge #GOLD #centralbank