Storage is one of those things most people only notice when it fails. When it works, it feels invisible. You upload something, you expect it to stay there, and you move on. But in open networks, storage is not a background detail. It is one of the hardest problems to solve properly, because the network itself is always changing. Machines go offline, new ones appear, and connections are never perfectly reliable. Walrus starts from this reality instead of pretending it doesn’t exist.

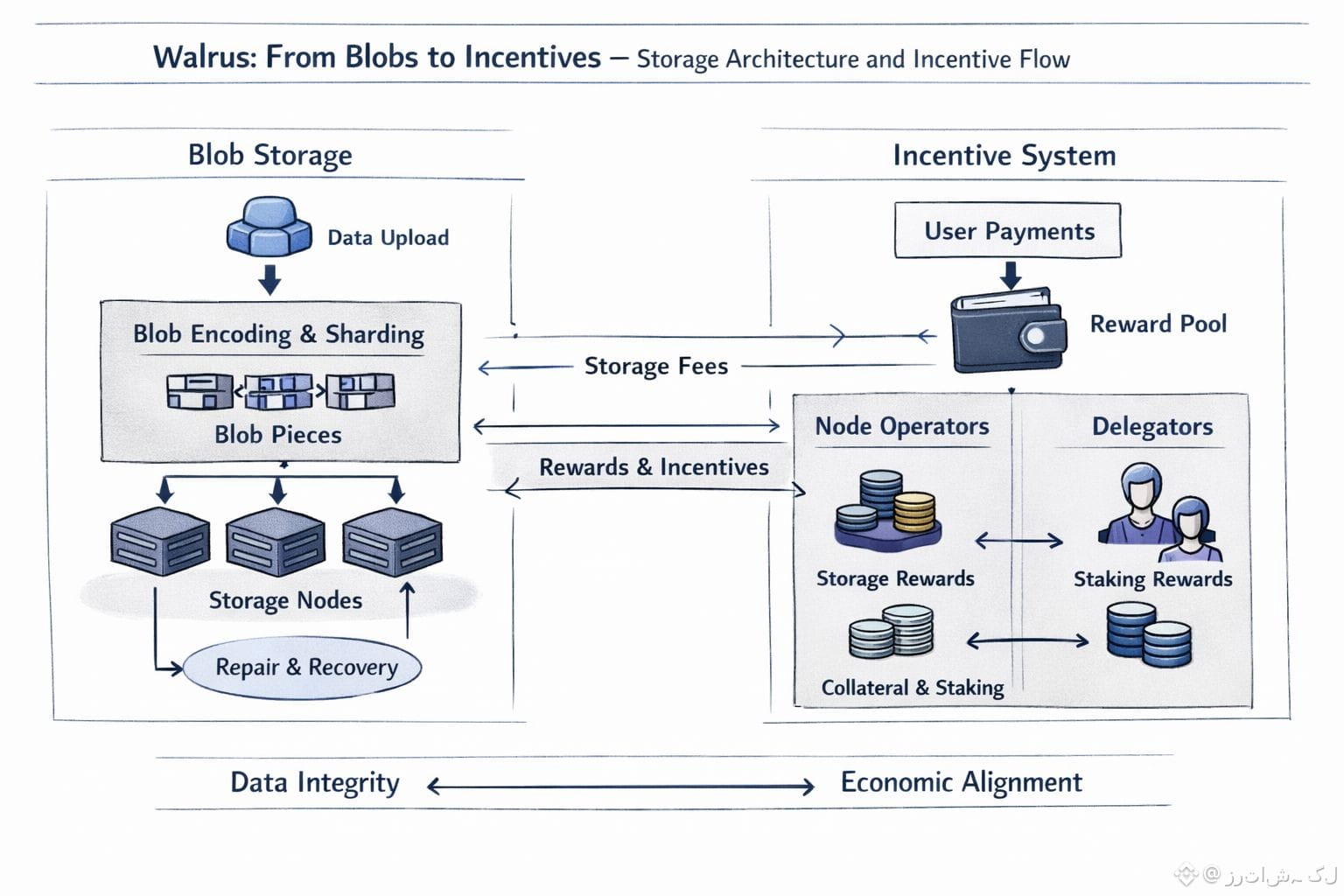

At the center of Walrus is a simple idea: store data as blobs. A blob is just a large piece of data, like an image, a video, or a chunk of application state. Walrus does not try to organize these like files in folders. It treats them as objects that need to survive in an environment where nothing stays still for very long. When a blob is stored, it is not copied again and again in full. Instead, it is transformed into structured pieces and spread across many storage nodes. As long as enough of those pieces remain available, the original data can always be rebuilt.

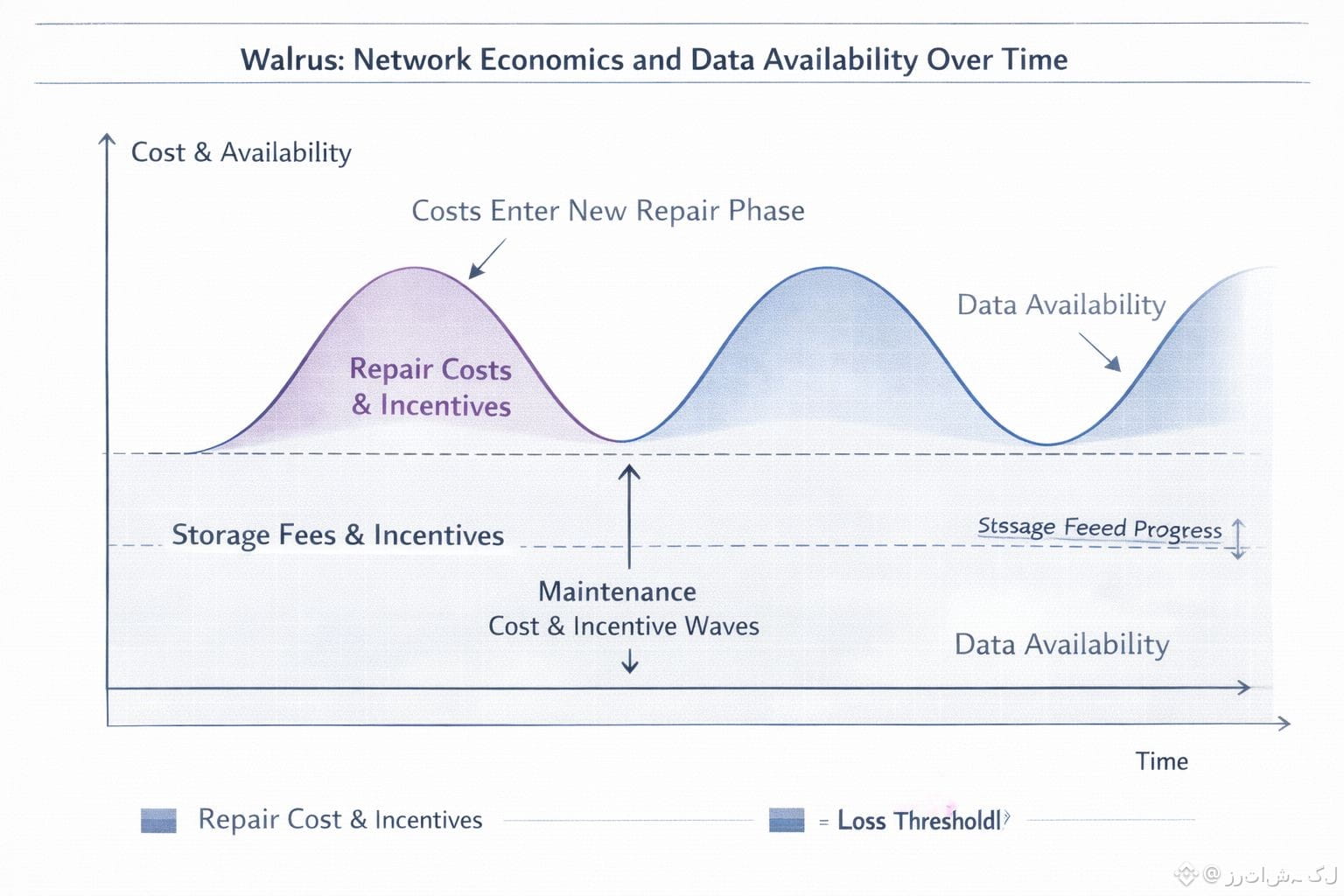

This design changes how the network behaves when something goes wrong. In many systems, even small failures can cause big repair work. In Walrus, small problems are usually fixed with small actions. If a few pieces disappear, only those pieces need to be restored. The rest of the data stays where it is. This keeps the network from constantly doing heavy work just to stay in the same place, and it makes long-term storage more stable and predictable.

But technology alone does not keep a network alive. There also has to be a reason for people to run nodes, provide space, and keep things working over time. Walrus connects its storage design to an incentive system that treats storage as an ongoing service rather than a one-time action. When someone pays to store data, that payment supports the network over the period the data is kept, not just at the moment it is uploaded. The people who operate storage nodes and the people who support them receive compensation as long as they continue to do their job.

This creates a simple and healthy relationship between the network and its participants. If you want to keep earning, you have to keep storing data correctly. If you stop doing that, you stop being useful to the system. There is no need to rely on trust or good intentions. The structure of the system itself pushes everyone toward the same goal: keep data available and in good condition.

Walrus also makes it possible for people to participate in different ways. Some run storage nodes and handle the technical work. Others support them through staking and delegation without needing to operate hardware themselves. This spreads responsibility across many independent participants and makes it easier for the network to grow without turning storage into something only large operators can afford to do.

What makes this interesting is how closely the technical side and the economic side depend on each other. The reason Walrus can aim for reasonable long-term costs is not just because of its incentive model. It is also because the storage design itself avoids unnecessary work. When repairs are local and limited, the network spends less bandwidth and less energy just keeping data alive. That makes it easier to keep storage pricing stable and predictable over time.

This matters for real applications. Many modern decentralized systems need to store large amounts of data that do not belong directly on a blockchain. Media, archives, and large datasets all need a place to live. If that place is too expensive or too fragile, developers end up falling back to centralized solutions, even if they would rather not. Walrus is trying to make decentralized storage feel like normal infrastructure: something you can rely on, plan around, and build on without constant worry.

There is also a deeper idea behind the system. Walrus does not treat storage as something that is finished once data is written. It treats storage as a process. Data is written, but it is also checked, maintained, and carried forward as the network changes. The incentive system exists to support that continuous work, not just the initial upload.

Seen this way, Walrus is not just offering a place to put data. It is trying to build a system where data can survive long periods of change without depending on any single operator or organization. By connecting how data is stored with how the network is rewarded, it is aiming for something practical, not perfect. Not a system that never fails, but a system that keeps working even when parts of it do.

That is what makes the project worth paying attention to. It is not built around big promises. It is built around the quieter, harder problem of keeping things running, year after year, in a world where nothing stays stable for very long.