Decentralized storage is one of the most important infrastructure layers for modern blockchains, and at the center of that layer are storage nodes. In Walrus, storage nodes are not passive warehouses that simply “hold files.” They are active participants that make data scalable, resilient, and economically sustainable, which is exactly what decentralized hosting like Walrus Sites depends on. Walrus Sites is on mainnet and is presented as the future of decentralized hosting: fully decentralized, cost-efficient, and globally available websites powered by Walrus. When a site is published to Walrus, its resources are stored as objects, the publisher receives an object ID and a URL, and anyone can access the site in a normal browser without a wallet. None of that works unless storage nodes do their job every minute of the day.

At a high level, a storage node is a machine that contributes disk space, bandwidth, and uptime to the Walrus network. The network assigns it encoded pieces of data to store, and the node must keep those pieces retrievable on demand. Walrus is built to stay reliable under real-world conditions, so nodes must handle normal churn, occasional outages, and uneven network connectivity. The point is not to pretend nodes never fail, but to design so the system keeps working when they do. This is why “highly resilient” hosting is not just a tagline; it is the end result of a storage layer designed around failure tolerance.

What a Storage Node Does in the Walrus Architecture

A Walrus storage node has three core jobs: store data fragments, prove they are being stored, and serve them when requested. Storage is the obvious part: the node writes its assigned pieces to disk and keeps them intact. Proof is the accountability layer: the node must respond to protocol challenges that demonstrate it still holds the data it claims. Serving is the performance layer: when users or applications request content, nodes deliver the required pieces quickly enough to reconstruct the original blob or object.

This is why storage nodes matter for Walrus Sites. A website is not a single file; it is a bundle of assets like HTML, CSS, images, fonts, and scripts. Walrus Sites stores these resources as objects, so the network can fetch and assemble them efficiently. As traffic grows, the system must keep assets available across geographies, and nodes are the distributed backbone that makes that possible.

Storage nodes also protect you from the classic web2 failure modes. In centralized hosting, a single provider outage, account suspension, or region-specific disruption can take a site down. In Walrus, the content is not tied to a single machine or a single company. Even if some nodes fail or disconnect, enough fragments remain available elsewhere for reconstruction. That is why resiliency is not a marketing word here; it is a property that emerges from how storage nodes store and distribute data.

Why Walrus Uses Dedicated Storage Nodes

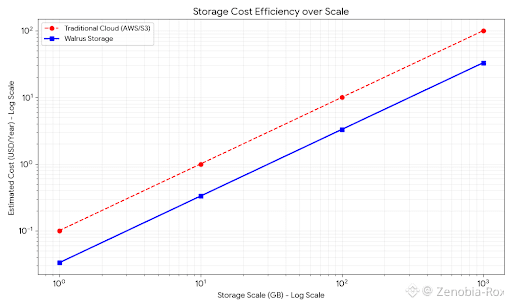

Traditional blockchains are expensive places to store data. Onchain storage replicates every byte across many validators, which makes costs explode and scalability collapse. Walrus takes a different approach: it separates data storage from execution, so blockchains can stay lean while still referencing large datasets. Instead of forcing every validator to store everything forever, Walrus relies on specialized storage nodes that are economically incentivized to do one job well: keep data available.

This design supports a broader idea: decentralized hosting should feel as simple as web2 while being more reliable than many web3 alternatives. Walrus Sites describes hosting that is competitive with traditional web2 solutions and more reliable than web3 alternatives. That claim is only believable if the storage layer is both efficient and dependable. Storage nodes make that possible because they can be run by many independent operators, scaled as demand grows, and held accountable by protocol rules. In other words, decentralization is not just “many computers exist,” it is “many computers are economically pushed to stay honest and online.”

Dedicated storage nodes also make it easier to specialize. Operators can tune hardware for storage and bandwidth rather than for transaction execution. They can optimize for uptime, network peering, and disk reliability. Over time, this creates a professional-grade storage layer, which is exactly what serious applications need if they want to serve users globally without “hosting headaches.”

Encoding, Distribution, and Resilience

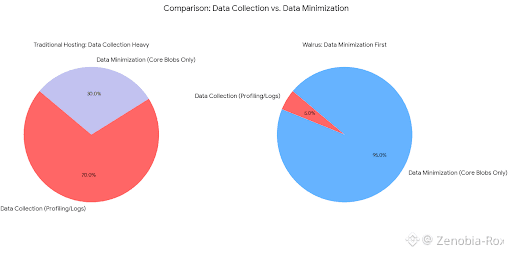

Walrus does not rely on naive replication where every node stores a full copy of each object. Instead, data is split, encoded, and distributed across many nodes. Encoding means the system can reconstruct the original object from a subset of pieces, so the network can survive node failures without losing availability. Distribution means no single node is a single point of failure. Together, these properties create resilience: the site stays up even if some nodes go offline.

The Walrus Sites page highlights this outcome directly: stored on Walrus, sites remain available and secure even in the face of node failures. That line describes the purpose of encoding and distribution. The network is designed so that failures are expected and absorbed, rather than treated as catastrophic events.

Resilience also matters for upgrades and movement. “All site resources are stored as objects, allowing them to be transferred at will” implies portability. If resources are objects, you can reference them, reuse them, and migrate them without being locked to a particular server setup. Storage nodes make that portability meaningful because objects are not trapped behind one endpoint. They live as data across many participants, so the system can keep serving them even as individual operators come and go.

Availability Proofs and Node Accountability

Because storage nodes are not trusted by default, Walrus needs verification. Availability proofs are the mechanism that turns “I store your data” into something measurable. The protocol can ask a node to produce specific pieces or cryptographic responses that demonstrate it has the required fragments. Nodes that fail to respond, respond too slowly, or respond incorrectly can be penalized, while nodes that respond reliably earn rewards.

This accountability is crucial for developers and businesses. When a team publishes a website, documentation hub, or dapp front end, they need to know it will remain accessible. They also need to explain reliability to users and, in serious settings, to auditors. A system that can verify storage behavior provides stronger guarantees than one that only hopes participants are honest.

Accountability also improves network health. Nodes that are consistently slow, frequently offline, or dishonest are economically discouraged from staying. Nodes that invest in good uptime and fast delivery are rewarded. Over time, that selection pressure improves the “average” quality of storage in the network, which directly improves the experience of anyone loading a Walrus Site.

The Economic Role of Storage Nodes

Storage nodes are infrastructure operators. They spend money on hardware, storage, bandwidth, and operations, and they expect consistent compensation for providing a reliable service. Walrus aligns incentives so that long-term uptime and correct behavior are rewarded. This is important because storage is not a one-time action; it is an ongoing responsibility.

In decentralized hosting, predictable costs matter as much as decentralization. Walrus Sites emphasizes cost-efficiency, and that can only happen if the storage layer avoids wasteful duplication while still providing strong availability. Efficient encoding, fair rewards, and penalties for unreliability together create a market where storage is both sustainable for operators and affordable for users.

A simple way to think about it is this: Walrus wants hosting to be boring. You publish your site, you get an object ID and a URL, and the site stays up. The economics of storage nodes are what keep that boring promise alive, because they turn uptime and availability into something nodes get paid for, not something they do out of goodwill.

How Storage Nodes Power Real Use Cases

Walrus Sites shows the kind of applications that benefit from this model: dapps, developer websites, and web3 community projects. The “How it works” flow is simple: create site code in any web framework, publish site to Walrus and receive the site’s object ID and URL, then access the site on any browser with no wallet required. Behind that simplicity is a set of storage nodes constantly storing, proving, and serving the underlying objects.

This matters beyond websites. Any application that needs durable data—media assets, historical records, rollup data availability blobs, or large configuration packages—can benefit from a storage layer that is not constrained by blockchain replication. Storage nodes make the network useful for these workloads because they can scale horizontally as demand grows.

It also matters for decentralization of front ends. Many “decentralized” apps still rely on centralized web hosting for their user interface. That creates a weak point: you can have a decentralized protocol, but a centralized website. Walrus Sites directly targets that gap by letting teams deploy websites with ease—no servers, no hosting headaches—so the application’s interface can be as decentralized as the smart contracts behind it.

Security and Decentralization

Decentralization is not only about the number of nodes but also about their independence. When resources are stored as objects and distributed, they can be transferred, replicated, and recovered without relying on a single host or platform. That property reduces censorship risk and reduces the chance that a single outage takes everything down.

Walrus Sites emphasizes “fully decentralized” hosting where resources are stored as objects and can be transferred at will. Storage nodes enable that by holding the object fragments and making them retrievable through the network rather than through a central server. If one operator disappears, the network still has enough pieces elsewhere to keep the object available.

Security also benefits from distribution. When data is split into fragments, no single node needs to hold the entire object, which reduces the damage a single compromised operator can do. The system relies on redundancy and verification to keep availability intact. In that sense, storage nodes provide a practical form of defense-in-depth: many independent participants, each storing only part of the data, combined with proofs that the parts still exist.

Long-Term Reliability as a Design Goal

The most important thing to understand is that storage nodes make Walrus boring in the best way. They make availability routine. They make hosting predictable. They make decentralization practical for normal users who do not want to think about wallets or infrastructure. A user can open a Walrus Site in a browser, and the site loads because nodes in the background are doing their job.

This is why storage nodes are the backbone of Walrus. They turn decentralized storage from an abstract idea into a service that can support real websites and real applications. They store data efficiently, prove it reliably, serve it globally, and keep the system resilient even when parts of it fail. When you understand storage nodes, you understand the hidden machinery that makes Walrus Sites and the broader Walrus ecosystem work. And once you understand that, the promise of decentralized hosting stops feeling like theory and starts feeling like infrastructure.

For builders, that means confidence: publish once, share the object ID, and your content stays reachable. For users, it means open a link and read, watch, or interact instantly, without permission, accounts, or lock-in from any device.