Data has always grown faster than the systems built to manage it. What changes from decade to decade is not the fact of expansion, but the nature of what is being stored and why it matters. The next ten years will not be defined by more files, more images, or more backups alone. They will be defined by data that remains relevant over time and data that cannot afford to disappear because it underpins decisions, systems, and automated processes.

This is the context in which Walrus becomes important, not as another storage solution, but as a different answer to a different question. Walrus is not asking how cheaply data can be stored or how quickly it can be retrieved. It is asking how long data can remain meaningful in a world where computation, governance, and automation increasingly depend on memory.

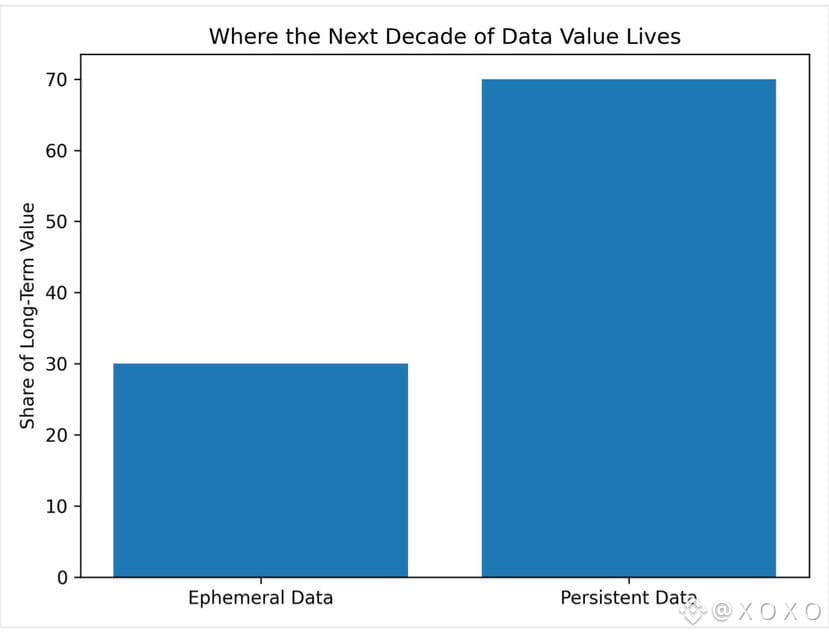

To understand Walrus’s role in the next decade, it helps to first understand how data itself is changing. Historically, most digital data was short-lived in relevance. Logs were rotated. Analytics expired. Content was valuable until it was replaced. Storage systems were optimized around this assumption. Durability was useful, but not foundational.

That assumption is breaking down.

Modern systems increasingly rely on historical continuity. AI models require long training histories and evolving datasets. Governance systems require records that can be audited years later. Financial and identity systems require proofs that outlast product cycles and even organizations themselves. In these environments, losing data is not an inconvenience. It is a structural failure.

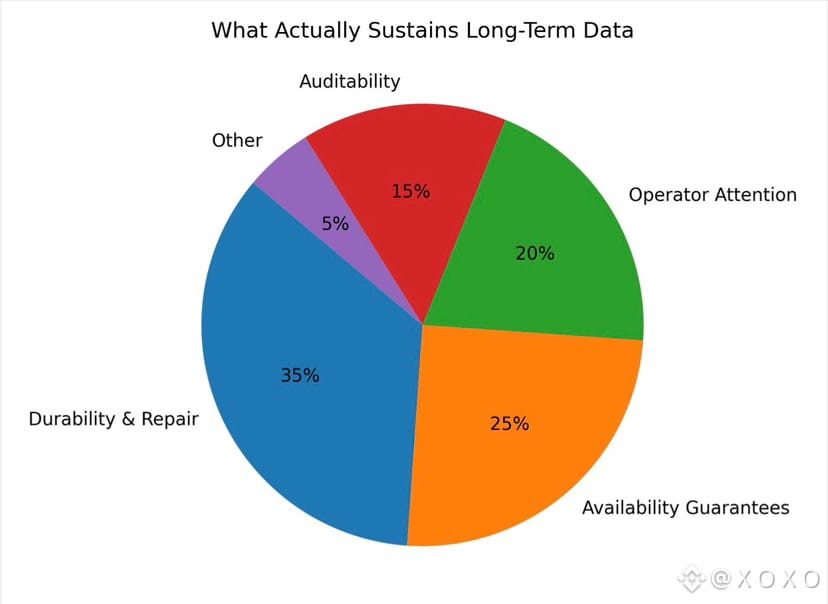

Walrus is built for this shift. Its core design treats data as something that is expected to survive time, not something that happens to do so. Blobs are not ephemeral artifacts. They are long-lived commitments with ongoing obligations attached to them. Repair eligibility, availability guarantees, and retrieval proofs are not emergency mechanisms. They are the steady background processes that keep data alive.

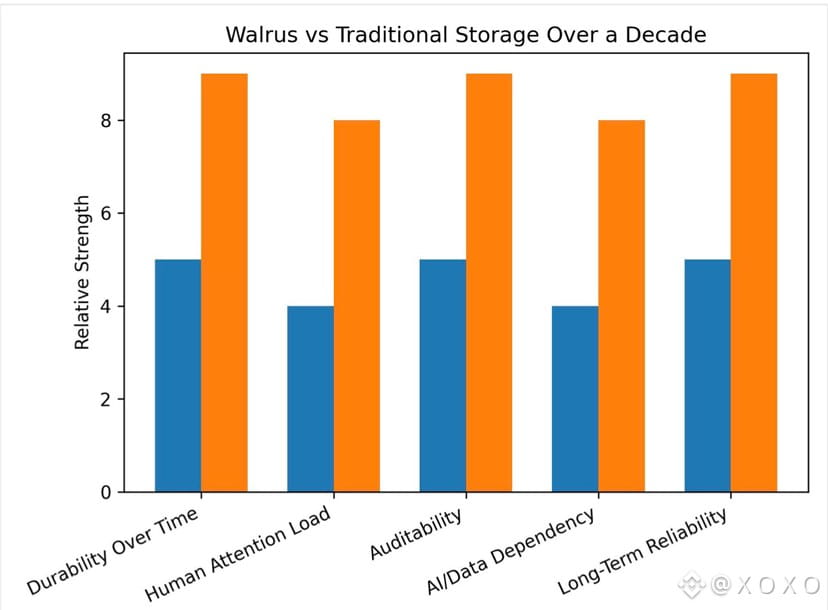

This distinction becomes more important as data volumes explode. Over the next decade, the amount of data generated by AI systems alone will dwarf what most traditional storage models were designed to handle. But volume is only part of the challenge. The harder problem is persistence at scale. Storing data once is easy. Keeping it available, verifiable, and repairable over years is not.

Walrus addresses this by shifting the burden from episodic intervention to continuous responsibility. Operators are not waiting for something to break. They are participating in a system where data continually asserts its right to exist. This changes the economics of storage. Costs are not front-loaded. They are distributed over time, aligned with the reality that long-lived data consumes attention and resources long after it is written.

In the next decade, this model becomes increasingly relevant because data is no longer passive. Data is becoming active infrastructure. AI agents reference historical states. Smart contracts depend on past commitments. Governance decisions rely on archived context. When data disappears, systems lose coherence.

Walrus provides a foundation for systems that cannot afford amnesia.

Another important shift is that data is no longer stored for humans alone. Machines increasingly consume data autonomously. AI agents do not forget unless systems force them to. They require consistent access to historical information to function correctly. This creates a new class of demand for storage systems that are predictable rather than cheap, and durable rather than fast.

Walrus fits naturally into this future. Its emphasis on availability over time, rather than throughput in the moment, aligns with machine-driven workloads that operate continuously. These systems do not generate dramatic spikes. They generate constant background demand. Over a decade, that kind of demand compounds into something far more significant than bursty usage ever could.

There is also a governance dimension that becomes unavoidable as data scales. As more decisions are automated, the ability to audit how those decisions were made becomes critical. This requires records that are not just stored, but provably intact. Walrus’s design makes data persistence observable. Proofs pass or they do not. Repair eligibility exists or it does not. This creates a form of accountability that is difficult to achieve with opaque or centralized storage models.

Importantly, Walrus does not assume that operators will always be motivated by excitement or novelty. Over long time horizons, those incentives decay. Instead, it embeds persistence into the protocol itself. Data continues to demand maintenance whether anyone is paying attention or not. This is uncomfortable, but it is honest. Long-lived data creates long-lived obligations.

In the next decade, this honesty becomes a strength. Many systems will fail not because they are attacked or overloaded, but because they quietly lose the human attention required to maintain them. Walrus surfaces this risk early. It forces networks to confront the cost of durability rather than pretending it does not exist.

Another role Walrus plays is in redefining what reliability means. Today, reliability is often measured by uptime during incidents. In the future, reliability will be measured by whether data remains accessible and correct after years of disinterest. Walrus is designed for that metric. Its success is boring by design. When it works, nothing dramatic happens. Data simply continues to exist.

This has implications for how infrastructure is evaluated. Over the next decade, the most valuable storage systems may not be the ones with the most impressive benchmarks, but the ones that quietly accumulate trust by never losing memory. Walrus positions itself squarely in that category.

There is also an ecosystem effect to consider. As more systems rely on durable data, they become harder to migrate. Historical context becomes a form of lock-in, not through technical barriers, but through dependency. When governance records, AI training data, or financial proofs live in one place for years, moving them is not trivial. Walrus benefits from this dynamic, not by trapping users, but by becoming part of the long-term structure of systems.

Over a decade, this creates a compounding effect. Early data stored on Walrus becomes the foundation for later systems. New applications build on old records. Value accrues not because of growth alone, but because of continuity.

From a macro perspective, Walrus represents a shift away from storage as a commodity and toward storage as infrastructure. Commodities compete on price and efficiency. Infrastructure competes on trust and longevity. In a world of exploding data, trust and longevity become more scarce than capacity.

Walrus’s role, then, is not to store everything. It is to store what matters when time passes.

That is a subtle distinction, but it is the one that will define the next decade of data expansion. As systems grow more autonomous, more regulated, and more dependent on historical context, the cost of forgetting will rise. Walrus is built for that world. It does not optimize for moments of excitement. It optimizes for years of quiet responsibility.

In the long run, data that survives boredom, neglect, and the absence of attention is the data that shapes systems. Walrus is not trying to be noticed in every cycle. It is trying to still be there when cycles are forgotten.

That may be the most important role a storage network can play in the decade ahead.