I still remember the moment clearly because it felt stupid in a very specific way. I was sitting in a crowded hostel room, phone on 5% battery, watching a match-based game resolve a reward outcome I had already “won” hours earlier. The gameplay was done. My skill input was done. Yet the final payout hinged on a server-side roll I couldn’t see, couldn’t verify, and couldn’t contest. When the result flipped against me, nobody cheated me directly. There was no villain. Just silence, a spinning loader, and a polite UI telling me to “try again next round.”

That moment bothered me more than losing money. I’ve lost trades, missed entries, and blown positions before. This felt different. The discomfort came from realizing that once gameplay outcomes affect real income, randomness stops being entertainment and starts behaving like policy. And policy without accountability is where systems quietly rot.

I didn’t lose faith in games that night. I lost faith in how we pretend randomness is harmless when money is attached.

What struck me later is that this wasn’t really about gaming at all. It was about delegated uncertainty. Modern systems are full of moments where outcomes are “decided elsewhere” — by opaque algorithms, proprietary servers, or legal fine print — and users are told to accept that uncertainty as neutral. But neutrality is an illusion. Randomness always favors whoever controls the dice.

Think of it like a vending machine with variable pricing. You insert the same coin, press the same button, but the machine decides the price after you’ve paid. We wouldn’t call that chance; we’d call it fraud. Yet digital systems normalize this structure because outcomes are fast, abstract, and hard to audit.

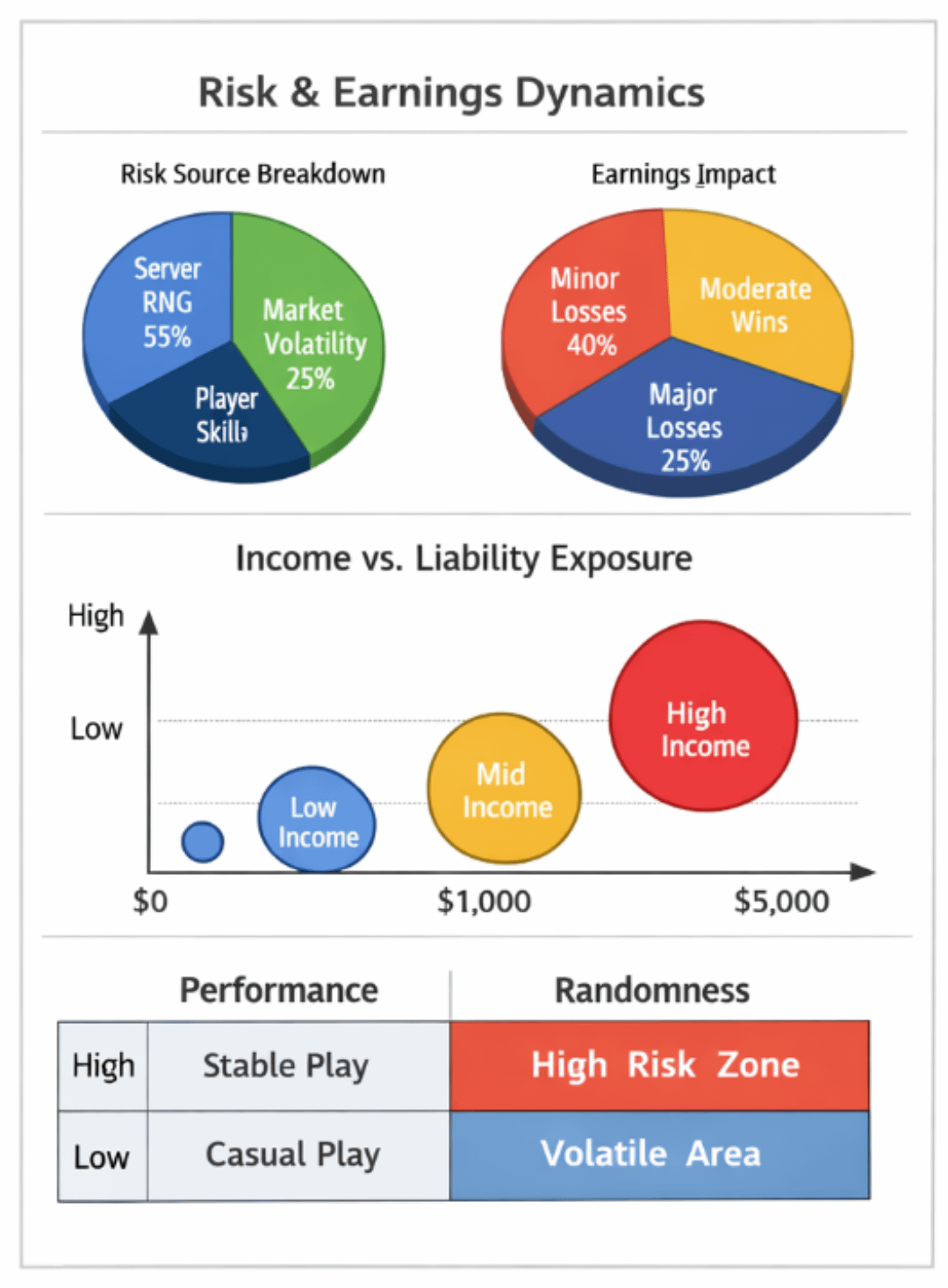

The deeper problem is structural. Digital environments collapsed three roles into one: the referee, the casino, and the treasury. In traditional sports, the referee doesn’t own the betting house. In financial markets, exchanges are regulated precisely because execution and custody can’t be trusted to the same actor without oversight. Games with income-linked outcomes violate this separation by design.

This isn’t hypothetical. Regulators already understand the danger. That’s why loot boxes triggered legal action across Europe, why skill-gaming platforms in India live in a gray zone, and why fantasy sports constantly defend themselves as “skill-dominant.” The moment randomness materially impacts earnings, the system inches toward gambling law, consumer protection law, and even labor law.

User behavior makes this worse. Players tolerate hidden randomness because payouts are small and losses feel personal rather than systemic. Platforms exploit this by distributing risk across millions of users. No single loss is scandalous. Collectively, it’s a machine that prints asymmetric advantage.

Compare this to older systems. Casinos disclose odds. Financial derivatives disclose settlement rules. Even national lotteries publish probability tables. The common thread isn’t morality; it’s verifiability. Users may accept unfavorable odds if the rules are fixed and inspectable. What they reject — instinctively — is post-hoc uncertainty.

This is where the conversation intersects with infrastructure rather than games. The core issue isn’t whether randomness exists, but where it lives. When randomness is embedded inside private servers, it becomes legally slippery. When it’s externalized, timestamped, and replayable, it becomes defensible.

This is the lens through which I started examining on-chain gaming architectures, including Vanar. Not as a solution looking for hype, but as an attempt to relocate randomness from authority to mechanism.

Vanar doesn’t eliminate randomness. That would be dishonest and impractical. Instead, it shifts the source of randomness into a verifiable execution layer where outcomes can be independently reproduced. That distinction matters more than marketing slogans. A random result that can be recomputed is legally and philosophically different from a random result that must be trusted.

Under the hood, this affects how disputes are framed. If a payout is contested, the question changes from “did the platform act fairly?” to “does the computation resolve identically under public rules?” That’s not decentralization for its own sake; it’s procedural defensibility.

But let’s be clear about limitations. Verifiable systems increase transparency, not justice. If a game’s reward curve is exploitative, proving it works as designed doesn’t make it fair. If token incentives encourage excessive risk-taking, auditability won’t protect users from themselves. And regulatory clarity doesn’t automatically follow technical clarity. Courts care about intent and impact, not just architecture.

There’s also a performance trade-off. Deterministic execution layers introduce latency and cost. Casual players don’t want to wait for settlement finality. Developers don’t want to optimize around constraints that centralized servers avoid. The market often chooses convenience over correctness — until money is lost at scale.

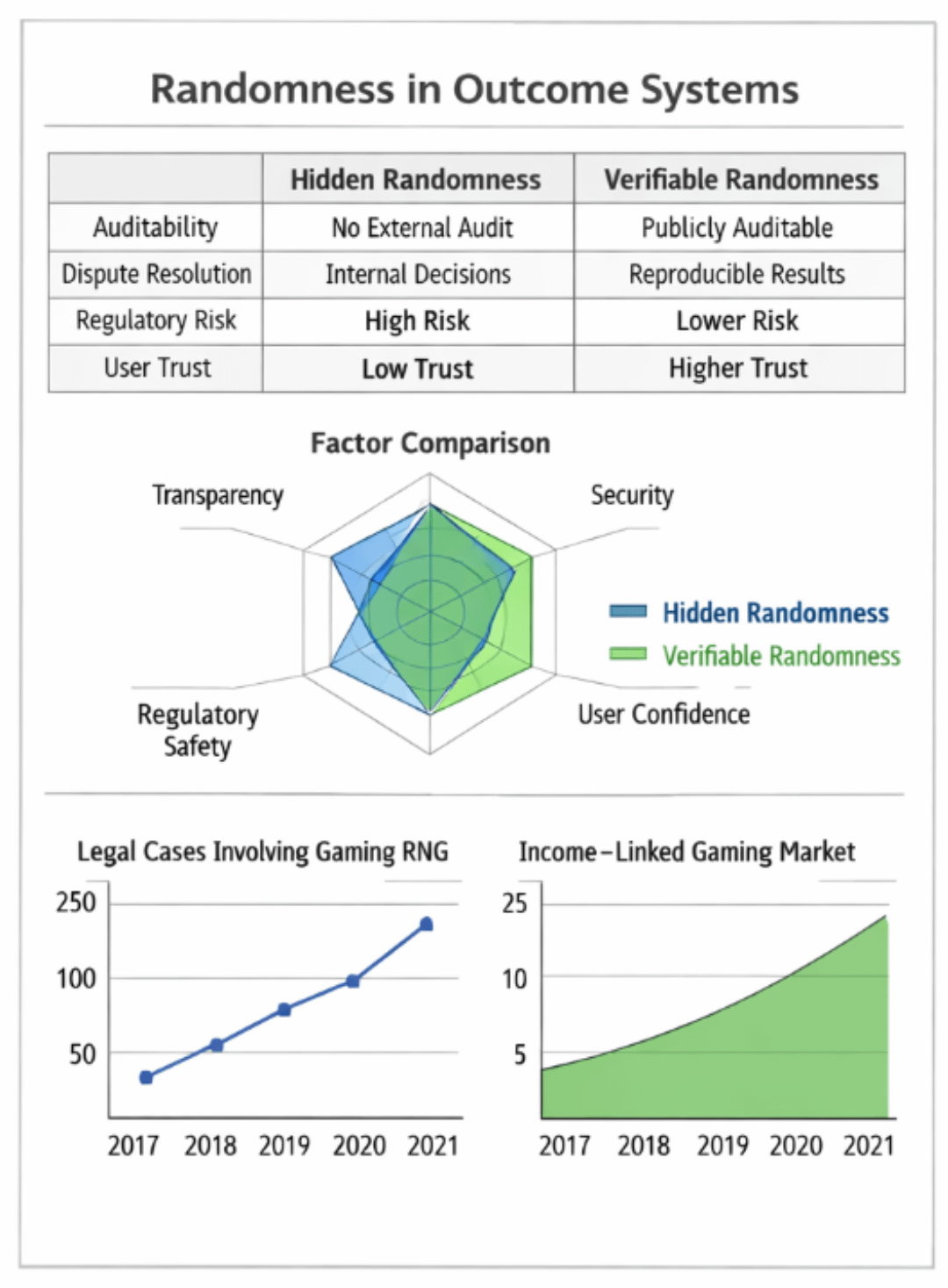

Two visuals help frame this tension.

The first is a simple table comparing “Hidden Randomness” versus “Verifiable Randomness” across dimensions: auditability, dispute resolution, regulatory exposure, and user trust. The table would show that while both systems can be equally random, only one allows third-party reconstruction of outcomes. This visual clarifies that the debate isn’t about fairness in outcomes, but fairness in process.

The second is a flow diagram tracing a gameplay event from player input to payout. One path runs through a centralized server decision; the other routes through an execution layer where randomness is derived, logged, and replayable. The diagram exposes where power concentrates and where it diffuses. Seeing the fork makes the legal risk obvious.

What keeps nagging me is that the industry keeps framing this as a technical upgrade rather than a legal inevitability. As soon as real income is tied to play, platforms inherit obligations whether they like it or not. Ignoring that doesn’t preserve innovation; it delays accountability.

Vanar sits uncomfortably in this transition. It doesn’t magically absolve developers of responsibility, but it removes plausible deniability. That’s both its strength and its risk. Systems that make outcomes legible also make blame assignable.

Which brings me back to that hostel room. I wasn’t angry because I lost. I was uneasy because I couldn’t even argue my loss coherently. There was nothing to point to, no rule to interrogate, no process to replay. Just trust — demanded, not earned.

So here’s the unresolved tension I can’t shake: when games start paying rent, tuition, or groceries, can we keep pretending randomness is just fun — or will the law eventually force us to admit that invisible dice are still dice, and someone is always holding them?