I didn’t discover the problem through a whitepaper or a conference panel. I discovered it standing in line at a small electronics store, watching the cashier apologize to the third customer in five minutes. The card machine had gone “temporarily unavailable.” Again. I had cash, so I paid and left, but I noticed something small: the cashier still wrote down every failed transaction in a notebook. Not for accounting. For disputes. Because every failed payment triggered a chain of blame—bank to network, network to issuer, issuer to merchant—and none of it resolved quickly or cleanly.

That notebook bothered me more than the outage. It was a manual patch over a system that claims to be automated, instant, and efficient. The friction wasn’t the failure itself; failures happen. The friction was who absorbed the cost of uncertainty. The customer lost time. The merchant lost sales. The bank lost nothing immediately. The system functioned by quietly exporting risk downward.

Later that week, I hit the same pattern online. A digital subscription renewal failed, money got debited, access was denied, and customer support told me to “wait 5–7 business days.” Nobody could tell me where the transaction was “stuck.” It wasn’t lost. It was suspended in institutional limbo. Again, the user absorbed the uncertainty while intermediaries preserved optionality.

That’s when it clicked: modern financial systems aren’t designed to eliminate friction. They’re designed to decide who carries it.

Think of today’s payment infrastructure less like a highway and more like a warehouse conveyor belt. Packages move fast when everything works. But when something jams, the belt doesn’t stop. The jammed package is pushed aside into a holding area labeled “exception.” Humans then deal with it manually, slowly, and often unfairly. Speed is optimized. Accountability is deferred.

Most conversations frame this as a technology problem—legacy rails, slow settlement, outdated software. That’s lazy. The real issue is institutional asymmetry. Large intermediaries are structurally rewarded for ambiguity. If a system can delay finality, someone else carries the float risk, the reputational damage, or the legal exposure. Clarity is expensive. Uncertainty is profitable.

This is why friction never disappears; it migrates.

To understand why, you have to look beyond “payments” and into incentives. Banks and networks operate under regulatory regimes that punish definitive mistakes more than prolonged indecision. A wrong settlement is costly. A delayed one is defensible. Issuers prefer reversibility. Merchants prefer finality. Users just want predictability. These preferences are incompatible, so the system resolves the tension by pushing ambiguity to the edges—where users and small businesses live.

Even “instant” systems aren’t instant. They’re provisional. Final settlement happens later, offstage, governed by batch processes, dispute windows, and legal frameworks written decades ago. The UI tells you it’s done. The backend knows it isn’t.

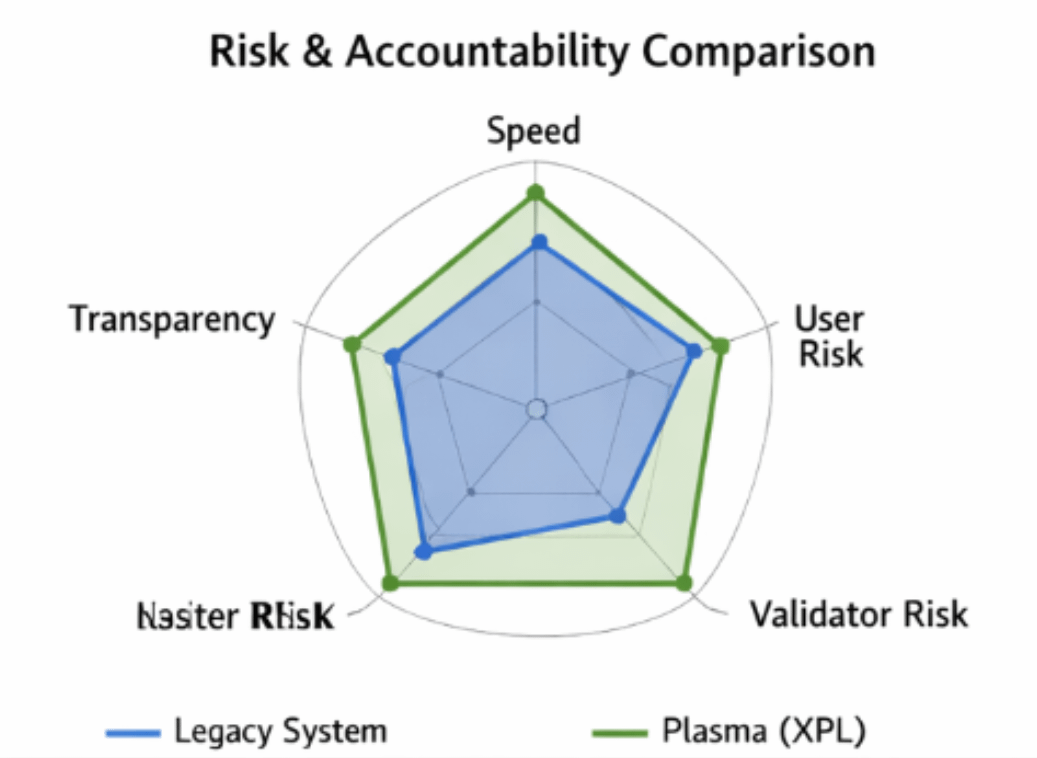

When people talk about new financial infrastructure, they usually promise to “remove intermediaries” or “reduce friction.” That’s misleading. Intermediation doesn’t vanish; it gets reallocated. The real question is whether friction is transparent, bounded, and fairly priced—or invisible, open-ended, and socially absorbed.

This is where Plasma (XPL) becomes interesting, not as a savior, but as a stress test for a different allocation of friction.

Plasma doesn’t try to pretend that payments are magically free of risk. Instead, its architecture shifts responsibility for settlement guarantees away from users and toward validators and issuers. In simple terms, users get faster, clearer outcomes because someone else posts collateral, manages compliance, and absorbs the consequences of failure.

That sounds great—until you ask who that “someone else” is and why they’d agree to it.

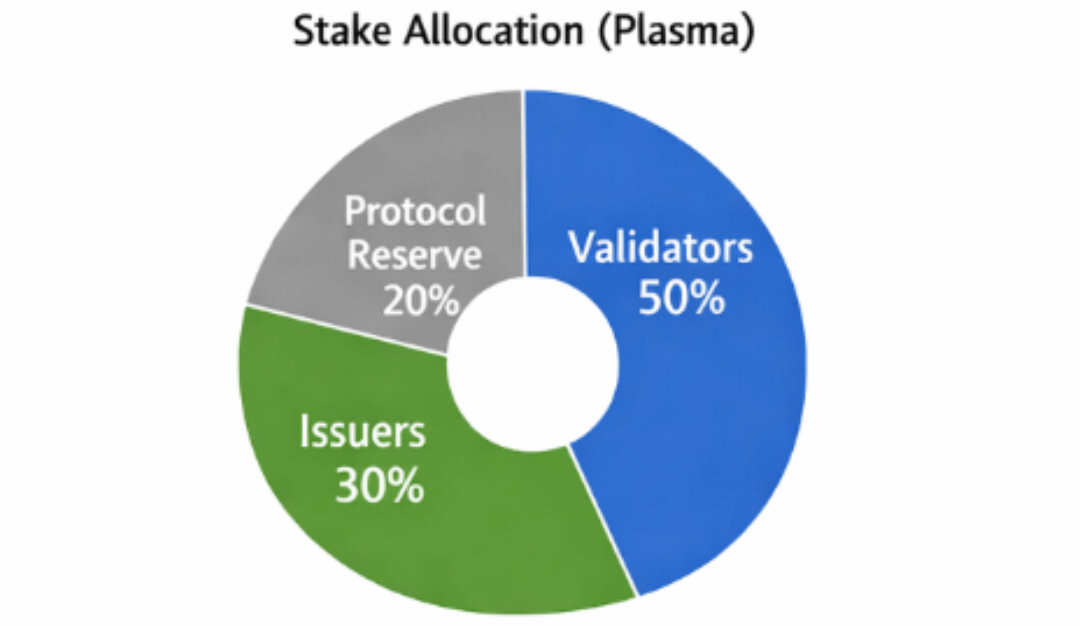

In Plasma’s model, validators aren’t just transaction processors. They’re risk underwriters. They stake capital to guarantee settlement, which means they internalize uncertainty that legacy systems externalize. Issuers, similarly, are forced to be explicit about backing and redemption, rather than hiding behind layered abstractions.

This doesn’t eliminate friction. It compresses it into fewer, more visible choke points.

There’s a trade-off here that most promotional narratives avoid. By relocating friction upward, Plasma raises the barrier to participation for validators and issuers. Capital requirements increase. Compliance burdens concentrate. Operational failures become existential rather than reputational. The system becomes cleaner for users but harsher for operators.

That’s not inherently good or bad. It’s a design choice.

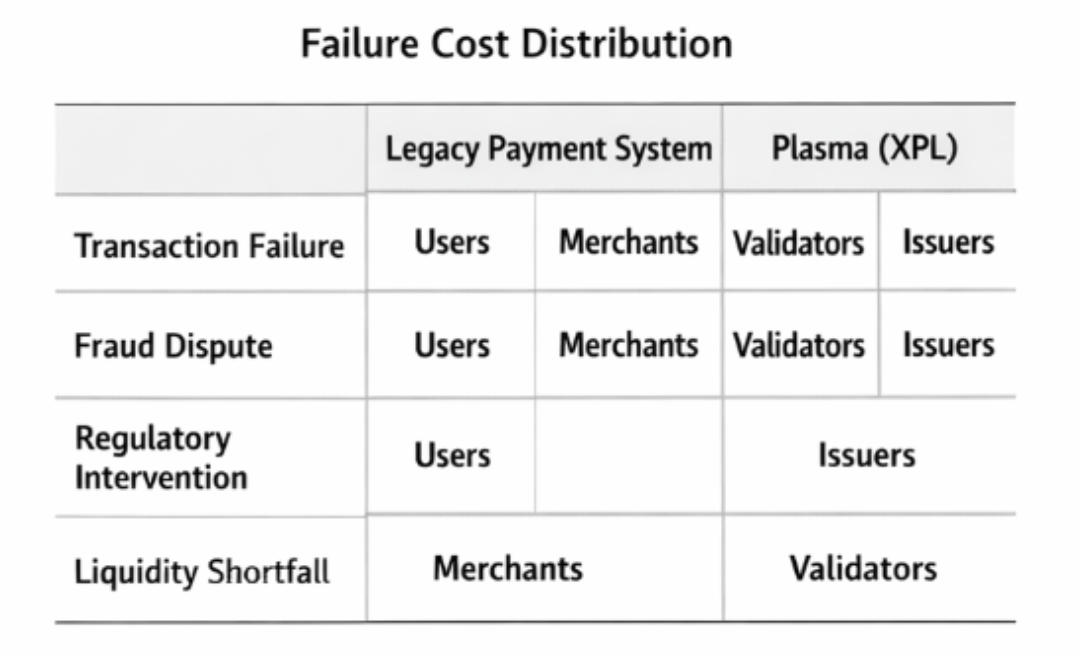

Compare this to traditional card networks. They distribute risk across millions of users through fees, chargebacks, and time delays. Plasma concentrates risk among a smaller set of actors who explicitly opt into it. One system socializes uncertainty. The other prices it.

A useful way to visualize this is a simple table comparing where failure costs land:

Friction Allocation Table

Rows: Transaction Failure, Fraud Dispute, Regulatory Intervention, Liquidity Shortfall

Columns: Legacy Payment Systems vs Plasma Architecture

The table would show users and merchants absorbing most costs in legacy systems, while validators and issuers absorb a higher share in Plasma. The visual demonstrates that “efficiency” is really about who pays when things go wrong.

This reframing also explains Plasma’s limitations. If validator rewards don’t sufficiently compensate for the risk they absorb, participation shrinks. If regulatory pressure increases, issuers may become conservative, reintroducing delays. If governance fails, concentrated risk can cascade faster than in distributed ambiguity.

There’s also a social dimension that’s uncomfortable to admit. By making systems cleaner for users, Plasma risks making failure more brutal for operators. A validator outage isn’t a support ticket; it’s a balance-sheet event. This could lead to consolidation, where only large, well-capitalized entities participate—recreating the very power structures the system claims to bypass.

Plasma doesn’t escape politics. It formalizes it.

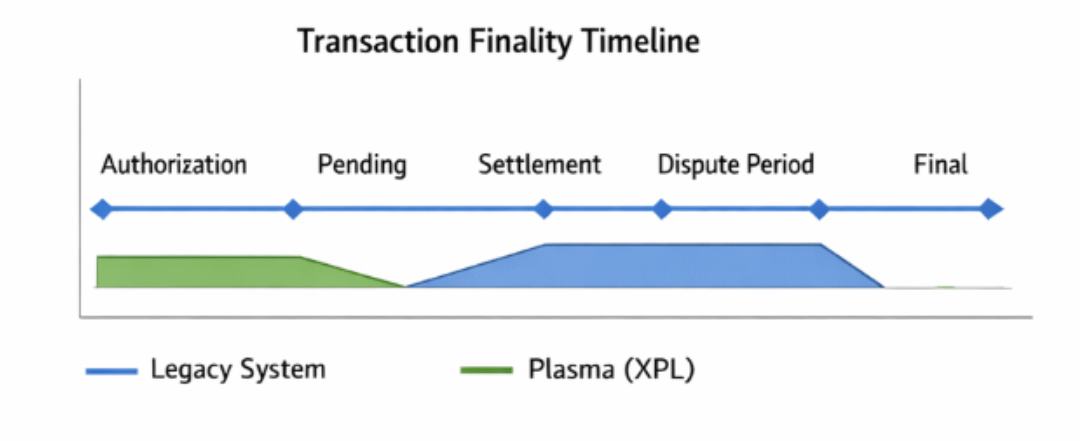

A second useful visual would be a timeline of transaction finality:

Visual Idea 2: Transaction Finality Timeline

A horizontal timeline comparing legacy systems (authorization → pending → settlement → dispute window) versus Plasma (execution → guaranteed settlement). The visual highlights not speed, but certainty—showing where ambiguity exists and for how long.

What matters here isn’t that Plasma is faster. It’s that it’s more honest about when a transaction is truly done and who is accountable if it isn’t.

After thinking about that cashier’s notebook, I stopped seeing it as incompetence. It was a rational adaptation to a system that refuses to assign responsibility cleanly. Plasma proposes a different adaptation: force responsibility to be explicit, collateralized, and priced upfront.

But that raises an uncomfortable question. If friction is no longer hidden from users, but instead concentrated among validators and issuers, does the system become more just—or merely more brittle?

Because systems that feel smooth on the surface often achieve that smoothness by hardening underneath. And when they crack, they don’t crack gently.

If Plasma succeeds, users may finally stop carrying notebooks for other people’s failures. But someone will still be writing something down—just with higher stakes and less room for excuses.

So the real question isn’t whether Plasma eliminates friction. It’s whether relocating friction upward creates accountability—or simply moves the pain to a place we’re less likely to notice until it’s too late.