I first noticed how people talk about VANRY the way they talk about a well-oiled machine. A flywheel. Spin it once, and the next turn gets easier. Spin it harder, and the thing starts to pull itself forward.

That’s the comforting version. The version you hear in community threads and quick explainers.

The less comforting version is that most “flywheels” in crypto aren’t wheels at all. They’re a few loosely connected belts, and the moment one belt slips, everything looks like it’s moving but nothing is actually being pulled forward.

Vanar’s story sits right on that edge. It’s not an empty story, and it isn’t automatically true either. It’s a design that could work in a narrow set of conditions, and it can also fail in the most boring way possible: not with a collapse, but with the token simply never capturing the value people assume it will.

So let’s talk about it like humans, not like a pitch deck.

VANRY starts with a plain job. It’s the chain’s gas token. That’s not controversial. The whitepaper frames it that way, explains that it came from a 1:1 swap out of the earlier token supply, and puts a maximum supply number on the table: 2.4 billion. It also makes something else clear: the supply doesn’t just sit there. More tokens are issued through block rewards over time. That’s how validators get paid, and how the network stays secure.

Already, you can feel the tension.

A flywheel needs traction. Issuance is friction. It’s not “bad.” It’s a cost. Like paying staff salaries. The question is whether the business grows faster than its costs.

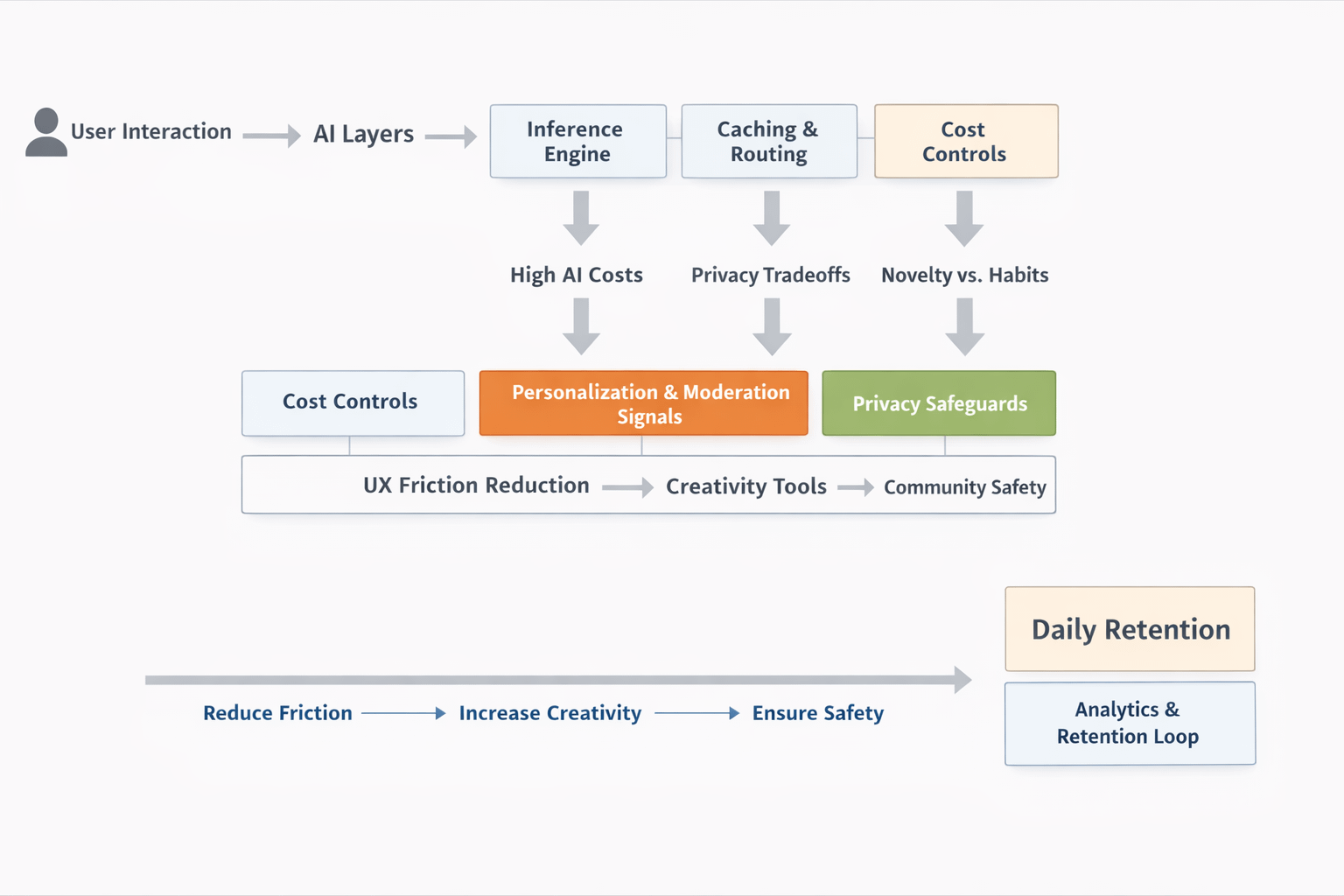

Then you get to Vanar’s choice that looks like a product decision but behaves like an economic decision: the fixed-fee idea.

Vanar doesn’t want users staring at fee charts and guessing whether today is a good day to click “confirm.” The whitepaper describes fees as stable in dollar terms. In other words, the chain aims to keep the user’s cost predictable, and it adjusts the amount of VANRY charged based on a computed market price.

As a user experience, that’s friendly. It’s the kind of thing a normal app user expects.

As token economics, it’s a little strange, because it flips a relationship people subconsciously rely on.

If fees are pegged to dollars, the chain doesn’t automatically “earn more VANRY” when the token price rises. It earns fewer tokens per transaction. So the token-demand from fees doesn’t scale neatly with price. It scales with volume. And because the stated fees are extremely low, that volume has to be enormous before it becomes meaningful compared with a supply in the billions.

This is the part that gets skipped when people explain the flywheel quickly. They’ll say “more usage = more demand,” and move on. The more honest version is: more usage creates demand, yes, but the demand is thin per unit of usage, so it needs scale to show up on-chain and in markets as something that can’t be ignored.

That’s why staking matters so much in the early years.

Staking is the chain’s way of borrowing credibility while it waits for real usage to arrive. People lock tokens, validators operate the network, rewards are paid out. The whitepaper also spells out that most of the additional issuance goes to validator rewards, with smaller slices for development incentives and community/airdrops.

Staking can help a token in a real way: it reduces the amount of supply that’s actually liquid. That can amplify price if demand does arrive.

But staking has its own ugly habit. If there isn’t enough real activity, the main “use case” becomes earning emissions. The system turns inward. People stake to earn rewards, they sell those rewards to cover opportunity cost, and the network’s biggest economy becomes the network paying itself.

Again: not a scandal, just a pattern.

So if Vanar stopped there—cheap fees, staking, block rewards—you’d basically be looking at the standard L1 token setup, just with a nicer fee experience.

The reason people bother talking about a “VANRY flywheel” is because Vanar claims a second engine: product revenue that gets routed back into the token.

This is where it gets interesting, and also where it gets fragile.

Vanar presents itself as more than blockspace. It leans into an AI-native stack and higher-level services. The implication is that people pay for actual products—subscriptions, tooling, enterprise usage—using normal money, not vibes. And then, according to Vanar’s own ecosystem messaging around buybacks and burns, a portion of that revenue is used to buy VANRY and burn it.

If that happens in a steady, measurable way, you start to get something closer to a real flywheel.

Because now you don’t have to rely entirely on “users buying gas” or “people buying to stake.” You’d also have a third source of demand: the platform itself acting like a recurring buyer, driven by revenue.

That’s not magic. It’s just a different kind of demand. And it’s the kind investors like because it doesn’t require every customer to become a token trader.

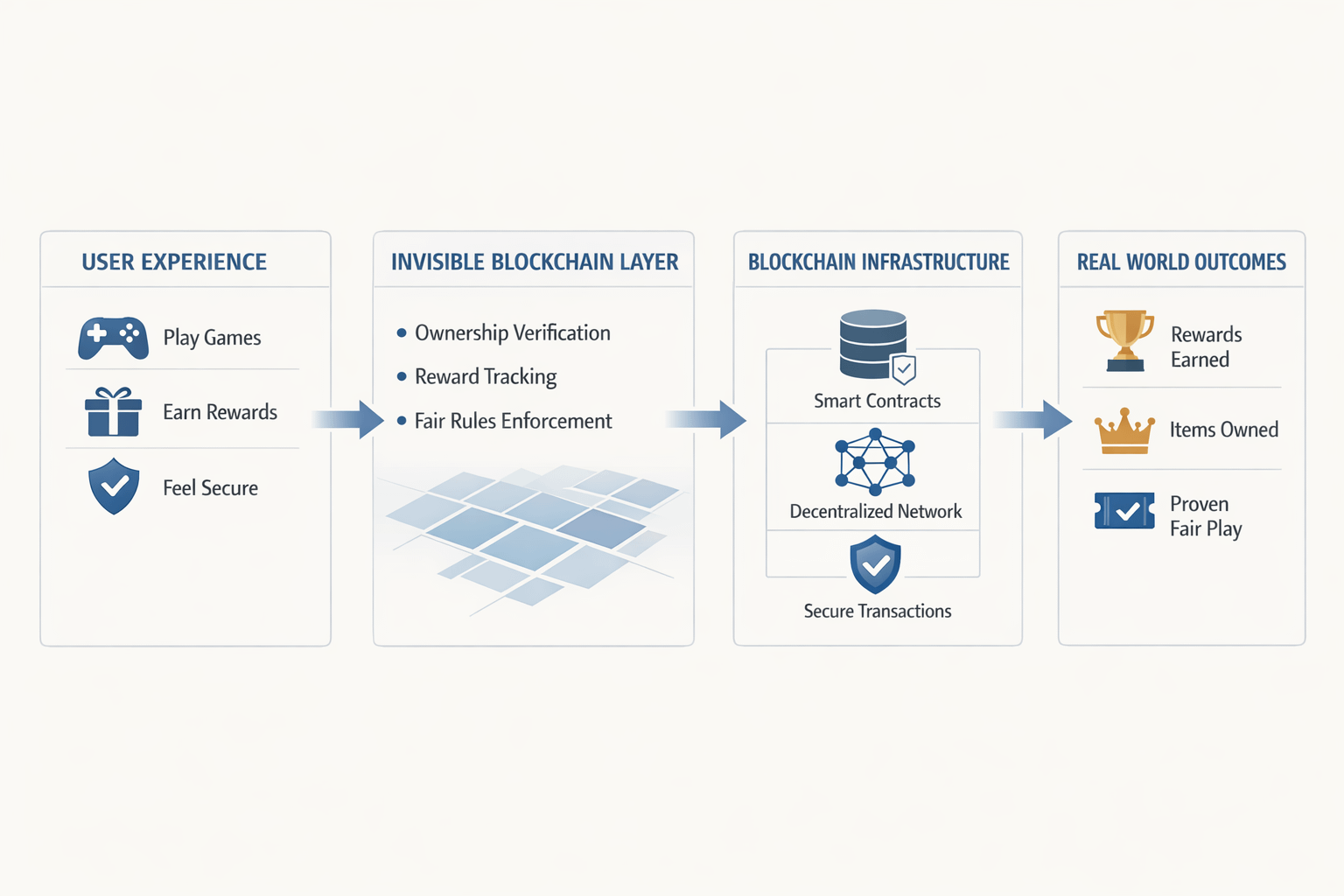

But here’s the human part: that loop only works if the revenue really gets routed the way the story says it does.

And in crypto, “routed” is where things get slippery.

There are only a few practical ways to implement buybacks:

One way is clean for customers but heavy on trust: customers pay in fiat or stablecoins, then the team (or a designated agent) buys VANRY in the open market on a schedule, and burns some portion.

It can work. But it means token demand depends on one actor’s choices, execution, and transparency. If the buying is clear, auditable, and consistent, the market treats it as structural. If it’s vague—occasional buy events, unclear percentages, discretionary timing—it gets treated like marketing.

Another way is clean for trust but rough for adoption: customers pay in VANRY directly, and burns are automatic. That reduces discretion, but it forces every customer to think about holding and spending a volatile token. Most businesses don’t want that friction.

So most projects pick the first approach and then spend the rest of their lives trying to convince people it’s not discretionary.

That’s why I keep coming back to the same dividing line:

Is VANRY capturing value mechanically, or politically?

Mechanically means the flow is built into the system and hard to quietly change. Politically means it exists as a policy decision: “we intend to do buybacks,” “we plan to burn,” “we’ll use revenue to support the token.” Those statements can be sincere. They’re still optional.

The flywheel breaks when optional becomes invisible.

There’s another crack that matters, and it’s less about mechanisms and more about belief: supply clarity.

Vanar’s whitepaper gives a specific supply story. But third-party trackers and older listings sometimes show tokenomics categories that look more conventional: team, advisors, marketing, vesting schedules. Sometimes that kind of mismatch is just outdated data. Sometimes it’s messy history from a token swap. Sometimes it’s poor indexing by aggregators.

Even if it’s benign, the mismatch is a problem for a flywheel narrative, because flywheels rely on trust.

If holders believe there’s hidden overhang—unlocks they don’t fully understand, discretionary treasury movements, allocations that feel opaque—they stop viewing buybacks and burns as “value capture” and start viewing them as “damage control.” And once the market adopts that mental model, the token has to work twice as hard to earn the same confidence.

Then there’s the less dramatic but more decisive failure mode: scale.

Vanar’s fee model aims for extremely low, predictable costs. That’s great for users, but it also means fee demand may remain a rounding error unless the chain is truly busy. In that world, the token’s biggest economic anchors become staking and the revenue-routing story.

If staking is mostly emissions-driven, and revenue-routing is small or unclear, you get a token that trades more on attention and incentives than on the underlying business.

That’s the “treadmill” outcome: lots of motion, limited pull.

So where does VANRY actually capture value, if everything goes right?

It captures value in three ways, each with its own risk.

One, it captures value if real usage explodes, because even tiny fixed fees add up at scale, and VANRY is still the unit used to pay them.

Two, it captures value if staking locks a meaningful share of supply, reducing float and making any demand more powerful.

Three, and most importantly, it captures value if revenue from products is consistently converted into market buying of VANRY and meaningful burns, in a way that’s repetitive enough to be boring.

Boring is the goal. Boring is credibility.

And if it breaks, it usually breaks in one of four ways.

Usage doesn’t reach scale, so fee demand stays thin.

Staking becomes the whole economy, so rewards become sell pressure instead of long-term support.

Revenue exists but leaks—spent on operations, partnerships, or held in stable assets—without reliably flowing back into the token.

Or the supply story gets noisy enough that no one wants to bet on scarcity, even if burns happen.

The uncomfortable conclusion is that VANRY is not one simple bet. It’s a bet that several parts of the machine work at the same time, and that the most discretionary part—the revenue-to-buyback loop—stays consistent when it would be easier not to.