@Walrus 🦭/acc When people say they’re “building onchain,” they usually mean logic and money. The awkward truth is that most applications are mostly data: images, game assets, training sets, video, logs, and the files that make software feel real. For years, teams either stored a tiny pointer onchain and hoped the rest stayed online somewhere, or they paid for centralized storage and accepted the trust trade. Walrus is showing up in the Sui ecosystem as a serious attempt to make that compromise less brittle, especially for builders who want data to remain verifiable and reachable without pretending the blockchain itself should store everything.

The timing matters. The demand isn’t coming from ideology as much as from product pressure. Games that update weekly can’t treat assets as an afterthought. Media projects want provenance and persistence without handing distribution back to a single platform. And the newest wave—agents, model-driven apps, and experiments around “onchain AI”—keeps running into the same wall: the app needs memory, datasets, and artifacts that outlive any single server or company decision. If you zoom out, it’s not hard to see why storage is suddenly getting pulled into the spotlight. What used to be “infrastructure” now shows up as a direct limiter on what an app can safely promise its users.

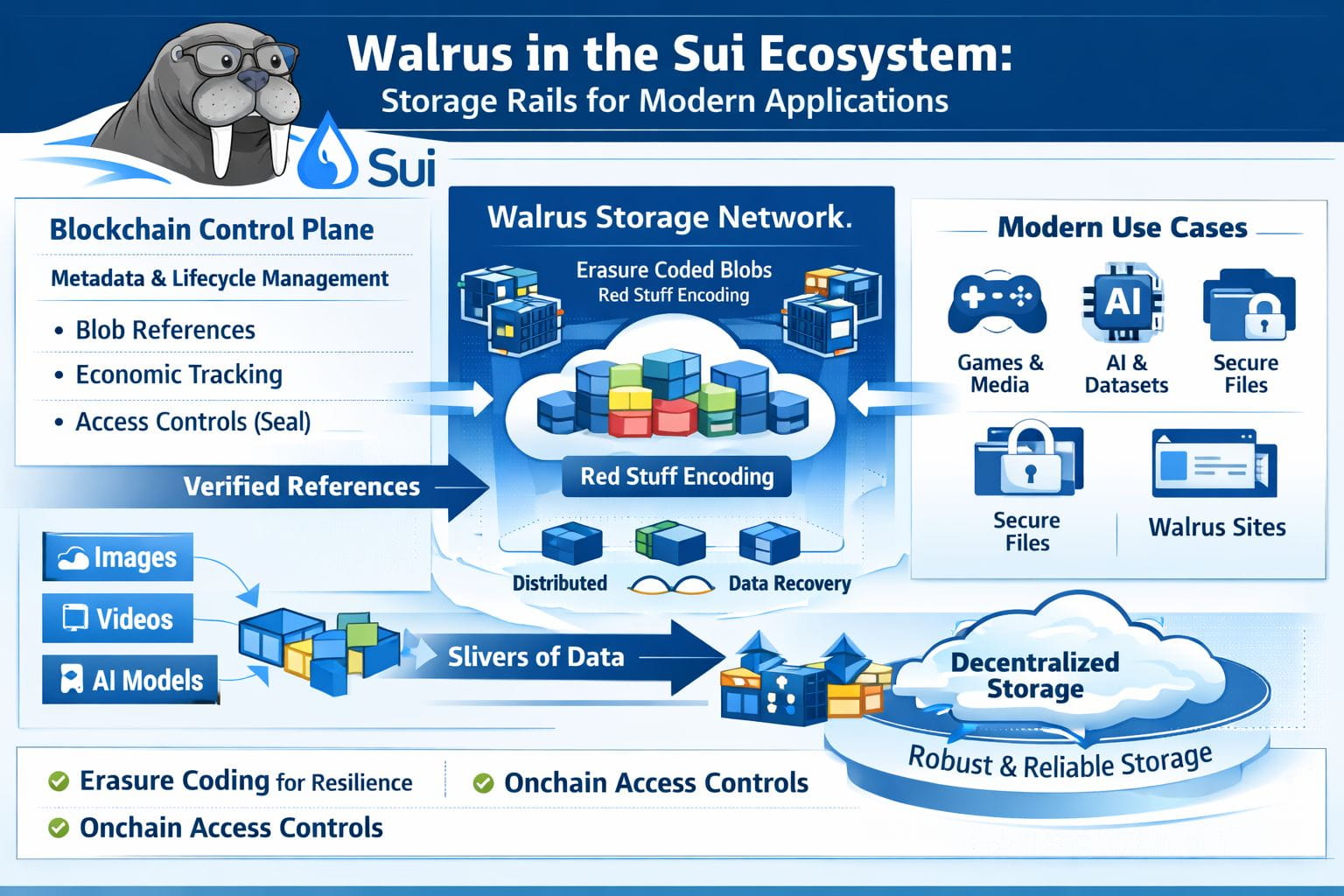

Walrus earns the “rails” framing because it treats storage as something programmable rather than a passive bucket. The design is intentionally split. Sui functions as the control plane: it tracks blob metadata, storage lifecycles, and the economics around who is paying for what and for how long. The big files don’t live on the chain. They sit out on Walrus storage nodes, while the chain keeps the small, important bits that need shared agreement and public visibility. It’s a practical trade: you avoid turning the blockchain into an overpriced hard drive, but you still get references you can verify instead of taking on faith.

Under the hood, Walrus focuses on unstructured “blob” storage and leans on erasure coding instead of simple replication. A blob is split into smaller pieces (often described as slivers), distributed across a committee of nodes for a given epoch. The idea is resilience without storing full copies everywhere: if some parts go missing, the network can reconstruct the blob from what remains. Walrus’s research describes a two-dimensional encoding scheme called Red Stuff, designed to recover lost data efficiently and to stay robust even as nodes come and go. This is the kind of detail that sounds academic until you’ve dealt with real-world churn and realize that “it usually stays online” is not an acceptable reliability plan.

The project’s milestones also help explain why it keeps coming up in conversations. Walrus was introduced publicly as a developer preview in mid-2024, and it launched on mainnet on March 27, 2025. That jump—from concept to a live network with clear developer-facing primitives—matters because storage protocols tend to live in perpetual “almost there” mode. Mainnet doesn’t automatically mean maturity, but it does move the discussion from theory to operational reality: pricing, uptime, tooling, and whether developers can integrate it without a heroic amount of custom work.

Where Walrus starts to feel distinctly “modern application” rather than “decentralized storage, again” is access control. In September 2025, Walrus introduced Seal, positioning it as encryption plus rules that can be enforced via onchain logic about who can read which data and under what conditions. That’s a pragmatic upgrade, because privacy and selective sharing are everyday requirements: paywalled media, private game state, gated datasets, internal files, and collaborative workflows where not everyone should see everything. Without something like this, builders drift back toward a familiar pattern where the blockchain is the branding layer and permissions quietly live in a centralized service.

#Walrus Sites makes the whole thing easier to picture. The documentation describes a path where a site is represented by a Sui object, the resources are mapped through onchain fields, and the actual site files are fetched from Walrus using blob IDs. It’s “static hosting,” but with a different trust model: updates are tied to ownership on Sui, and retrieval is tied to a decentralized storage network rather than a single host. I find that framing useful because it keeps the conversation grounded. The real question isn’t whether decentralized storage is morally better. It’s whether it can become boring infrastructure—reliable, debug gable, and ordinary enough that teams use it because it reduces risk, not because it signals identity.