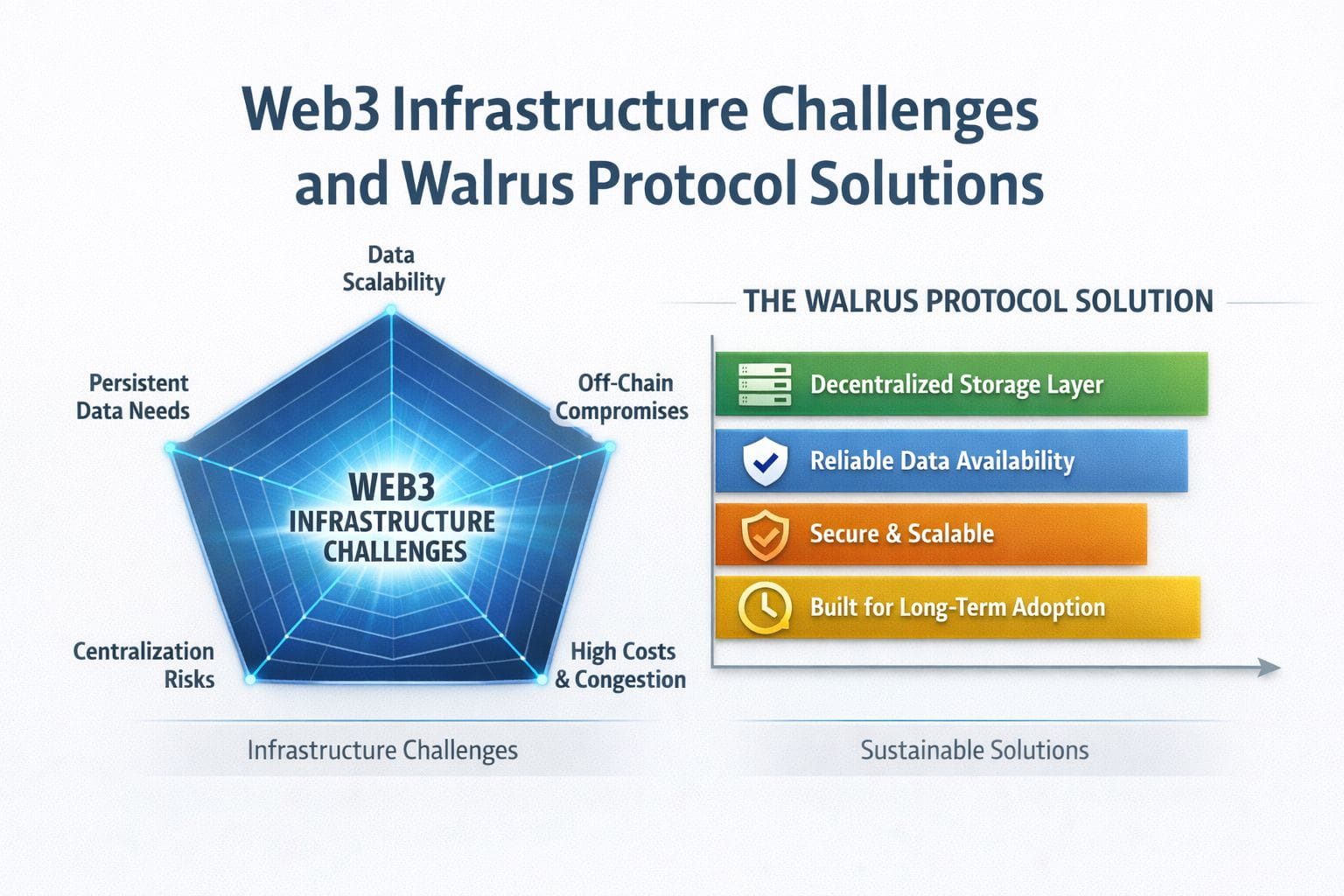

Every few years, Web3 goes through a phase where optimism runs ahead of infrastructure. New apps launch, new narratives form, and everything feels possible. But underneath that optimism, the same question keeps coming back: can the system actually support what people are building on it? That’s the question that led me to take a closer look at @Walrus 🦭/acc . A lot of Web3 today works because usage is still relatively contained. When data volumes are small, inefficiencies don’t scream they whisper. Developers can get away with off-chain storage. Centralized services can fill the gaps. Users don’t notice the compromises because nothing has broken yet. But scale has a way of exposing everything. As applications mature, they stop being lightweight experiments and start behaving like real software products. NFTs become more than images; they become access passes, identities, and compostable assets. Games turn into persistent worlds with evolving state. Social protocols generate streams of user-generated content that people expect to remain accessible. AI-integrated dApps produce and consume data continuously.

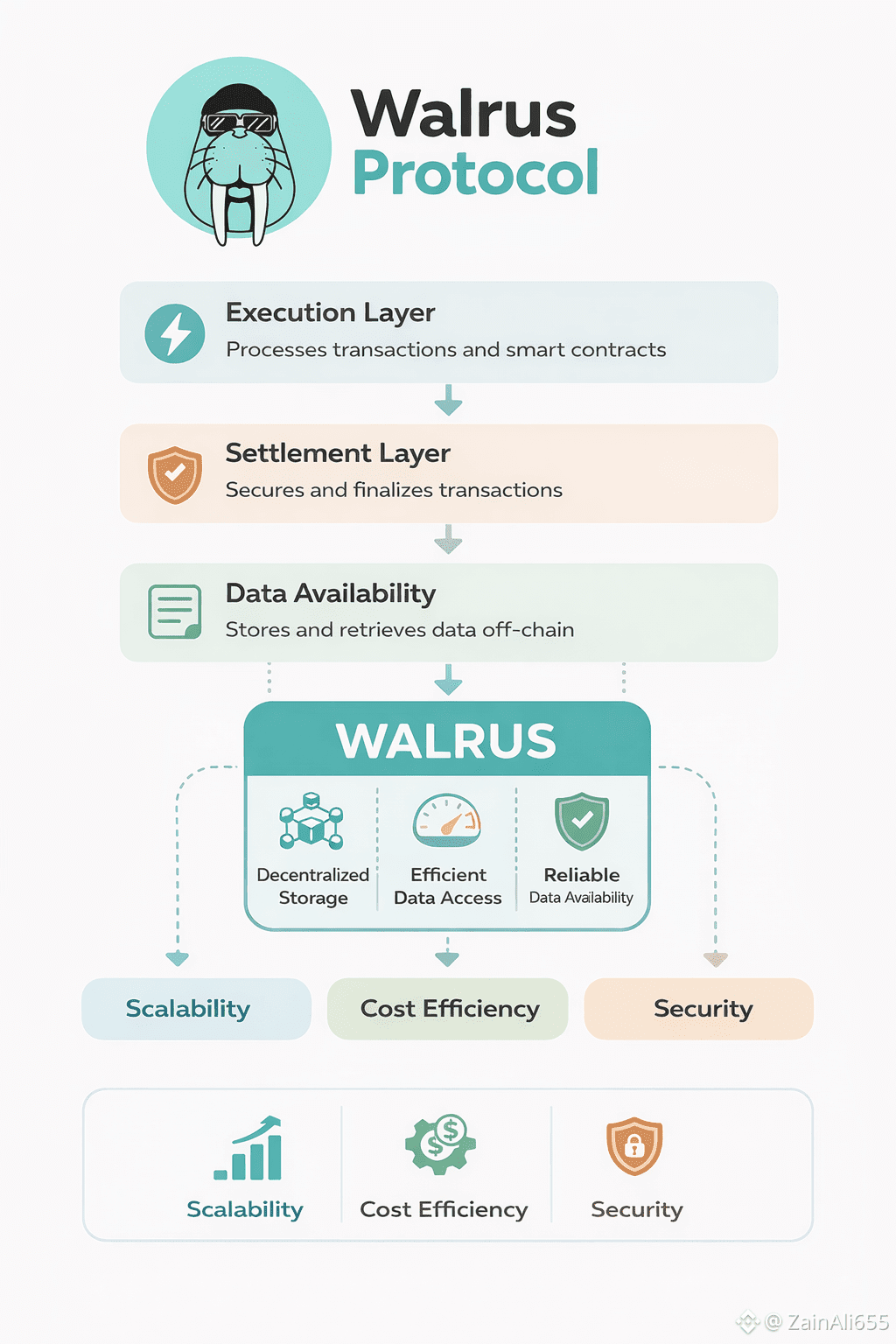

All of this creates a simple but uncomfortable truth: data grows faster than execution demand. Blockchains were designed to verify state transitions, not to store massive datasets indefinitely. Forcing them to do so leads to higher costs, congestion, and brittle workarounds. That’s why so much Web3 data quietly lives outside the chain, often in places that don’t share the same decentralization guarantees. Walrus exists because that model doesn’t scale cleanly. What stands out to me is that Walrus doesn’t try to patch the problem with shortcuts. It treats data availability and storage as their own layer something that deserves specialized design rather than being squeezed into existing constraints. That might sound subtle, but it’s actually a big shift in how Web3 systems are being thought about. We’re already seeing this shift elsewhere. Execution layers are optimizing for speed. Settlement layers are optimizing for security. Data availability layers are emerging because storing data efficiently and reliably is a different problem entirely. Walrus fits squarely into that evolution. What I also find interesting is how this reframes adoption expectations.

Infrastructure doesn’t explode into relevance overnight. It integrates slowly. One project uses it for metadata. Another for asset storage. Another for archival state. Each integration on its own looks small. Together, they create dependency and dependency is what gives infrastructure staying power. This is why I think many people underestimate storage protocols. They’re not exciting because they’re not meant to be noticed. When storage works, nobody celebrates it. When it fails, everything else stops mattering. That invisibility is a feature, not a flaw. From an economic standpoint, data demand behaves differently from speculative demand. People may trade less in bear markets, but content creation doesn’t stop. Games still update. NFTs still exist. That expectation doesn’t reset with market cycles.

This is why I see $WAL as aligned with a structural trend rather than a narrative one. It doesn’t rely on excitement to justify itself. It relies on a problem that grows quietly and consistently over time. Of course, none of this guarantees success. Storage is a competitive space. Developers care about cost, performance, and reliability far more than ideology. Walrus still has to prove that it can operate under real-world conditions at meaningful scale. Adoption takes time, and time introduces risk. But these are execution risks not conceptual ones. I’m far more comfortable evaluating whether a team can deliver on a clear need than betting on attention alone. And the need for decentralized, reliable data availability isn’t hypothetical. It’s already visible just partially hidden by temporary workarounds.

Another thing I think people overlook is how unforgiving users become once expectations shift. Early adopters tolerate broken links and missing assets. Mainstream users don’t. Once Web3 applications aim for broader audiences, infrastructure failures won’t be dismissed as “early tech.” They’ll be deal-breakers. Walrus feels like it’s being built with that future in mind. I’m not trying to frame this as a guaranteed outcome or a short-term opportunity. I’m simply observing where pressure is likely to build as Web3 matures. Data volume, persistence, and availability are at the center of that pressure.

If Web3 remains niche and experimental, projects like #walrus may never be fully appreciated. But if Web3 grows into real digital infrastructure something people rely on daily then decentralized storage and data availability stop being optional features. They become baseline requirements. That’s the context in which I’m evaluating walrus protocol. Not as a headline-grabber, but as part of the underlying stack that determines whether Web3 can actually scale without quietly compromising its core promises. Sometimes the most important work happens far away from the spotlight. Walrus feels like one of those cases.