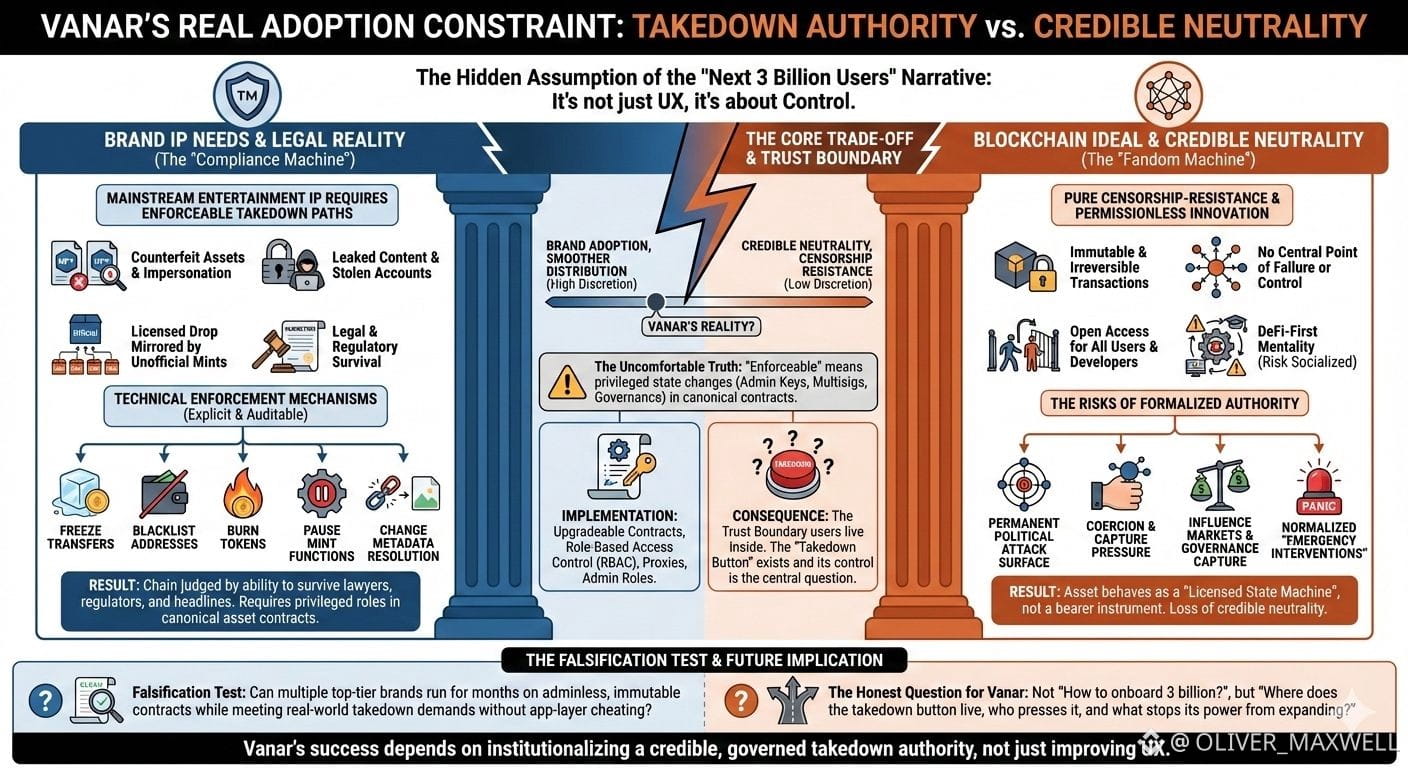

With Vanar selling a “next 3 billion users” story to entertainment and brands, I notice the same hidden assumption: that consumer adoption is mostly a product problem. Better wallets, cheaper fees, smoother onboarding, and the rest follows. For mainstream entertainment IP, I think that’s backwards. The first serious question a brand asks is not how fast blocks finalize, but what happens when something goes wrong in public. Counterfeit assets. Impersonation. Leaked content. Stolen accounts. A licensed drop being mirrored by a thousand unofficial mints within minutes. In that world, a chain isn’t judged by its throughput. It’s judged by whether there is an enforceable takedown path that can survive a lawyer, a regulator, and a headline.

The uncomfortable part is that “enforceable” is a technical word on-chain. A takedown request translates into explicit, role-gated state changes: freezing transfers, blacklisting addresses, burning tokens, pausing mint functions, or changing metadata resolution so an asset stops rendering. Those hooks live in the canonical asset contracts, and whoever controls the admin role or upgrade authority controls the outcome. If a contract cannot do those things, the chain cannot guarantee the kind of brand-grade compliance the IP owner is actually buying at the asset layer. And if the asset layer cannot guarantee that, the brand’s legal team will push the enforcement boundary up the stack until it finds something that can. That boundary always exists somewhere; the only question is whether it’s explicit and auditable, or hidden behind “we’re decentralized” language that collapses the first time an injunction arrives.

This is why I think Vanar’s brand and consumer thesis, and the way VANRY gets priced off that thesis, is mispriced. If you really want mainstream entertainment IP living on-chain, you are signing up for governance and admin surfaces that a pure censorship-resistance narrative treats as contamination. The easiest implementation is upgradeable contracts and role-based access control. A proxy can be upgraded. An admin can freeze. A multisig can pause. A governance vote can blacklist. That’s not a side detail. That is the trust boundary users end up living inside on Vanar when the core use case is brand drops and consumer IP. When an NFT is “owned” but can be invalidated, frozen, or made untradeable by a privileged role, the asset behaves more like a licensed state machine than a bearer instrument. You can call it compliant and consumer-friendly, but it stops being credibly neutral.

Once you accept that, the trade-off becomes brutally clear. Legal survivability buys you brand adoption, smoother distribution, and fewer existential partner risks. It also creates a permanent political attack surface. If the chain has a credible freeze path for IP, it has a credible freeze path for everything else that shares the same control plane. Even if you promise to use it only for obvious fraud, the system doesn’t care about intentions; it cares about capabilities. Capabilities attract pressure. Pressure attracts capture. Capture can be as simple as one compromised admin key, or as complex as governance turning into an influence market where “emergency interventions” become normal because the ecosystem has trained itself to expect reversibility.

I also think this is where many L1 narratives quietly cheat. For Vanar-style brand drops, teams can try to keep the base chain “neutral” while moving enforcement to applications: marketplaces delist items, official wallets refuse to display certain assets, bridges gate flows, and centralized support teams mediate disputes. That works for a while, but it breaks as soon as consumers learn that “takedown” in practice means “takedown in the official front end.” The asset still exists, still trades elsewhere, and still resurfaces as soon as attention shifts. If the goal is brand-safe consumer scale, enforcement that only works in one UI is not enforcement, it’s PR. So the pressure creeps downward, from app layer to canonical contracts, because that’s where you can actually change state across the entire ecosystem.

This is why I watch brand-driven chains differently from DeFi-first chains. DeFi systems can live with irreversibility as a feature and socialize risk through better tooling and user education. Entertainment IP cannot. Brands do not get to say “sorry, immutable” when a counterfeit collection goes viral. Their incentives are not aligned with maximal permissionlessness. They are aligned with controlling distribution, controlling perception, and controlling liability. If Vanar is serious about entertainment and brands, it will be rewarded for providing those controls, and punished for not providing them. That reward and punishment loop is stronger than any whitepaper principle.

The risk is that the moment you formalize takedown authority, you have to decide who holds it and under what constraints. Admin keys are fast but fragile. Multisigs are safer but still a single choke point. Governance is more legible but slower, easier to capture, and often ends up with emergency committees anyway because real-world deadlines do not wait for tokenholder deliberation. None of these options are clean. Each one shifts your system from credible neutrality toward credible discretion. And discretion is not free. It forces you to define process, evidence standards, appeal mechanisms, transparency, and limits. If you don’t define them, they will be defined for you by whatever crisis arrives first.

I think the most honest way to judge Vanar’s adoption thesis is to stop asking whether it can attract brands, and start asking what shape of authority it is willing to institutionalize to keep them. If the chain’s real future is a set of canonical brand contracts with privileged freeze and upgrade roles, then the pricing discussion should revolve around governance design, key management, public accountability, and how much discretion the ecosystem can tolerate before it becomes indistinguishable from a permissioned platform with a token. If, instead, Vanar wants to preserve strong censorship-resistance properties, it needs to explain how brands will survive without protocol-level takedown powers, and why that survival won’t simply reintroduce centralization through the back door.

The thesis has a clean falsification test, and I like angles that can be embarrassed by reality. If multiple top-tier brand launches can run for months on adminless, immutable asset contracts while still meeting real-world takedown demands, the argument weakens. The evidence would be visible: no privileged freeze, burn, pause, or blacklist functions in the canonical contracts, and no emergency governance interventions that effectively act as takedown mechanisms. Not “we could if we had to,” but “we didn’t, and the brand still operated.” If that happens at scale, then maybe the market is right that consumer adoption is mainly UX. My bet is it won’t, because mainstream IP is a compliance machine pretending to be a fandom machine, and the chain that hosts it will inherit that machinery whether it admits it or not.

So when I look at Vanar and VANRY through this lens, the implication is simple and not particularly comforting. The upside case is not just more users; it’s a chain that becomes a credible coordination layer for consumer IP under real-world constraints. The downside case is not just slower adoption; it’s governance and admin power becoming a permanent tax on neutrality, inviting coercion, capture, and quiet censorship that users only notice after it’s already normalized. If you want to take Vanar seriously, don’t ask how it onboards the next 3 billion. Ask where the takedown button lives, who can press it, and what stops that power from expanding the moment the first big brand demands it.