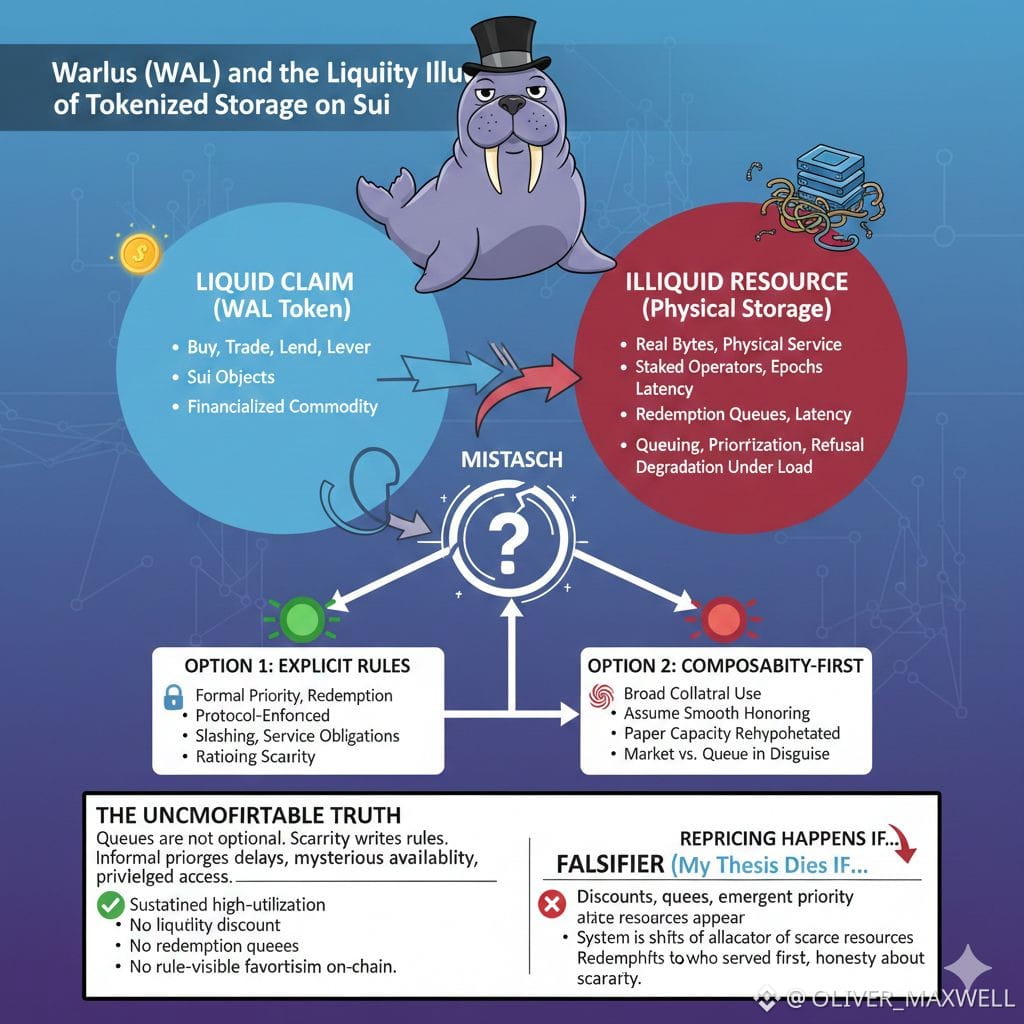

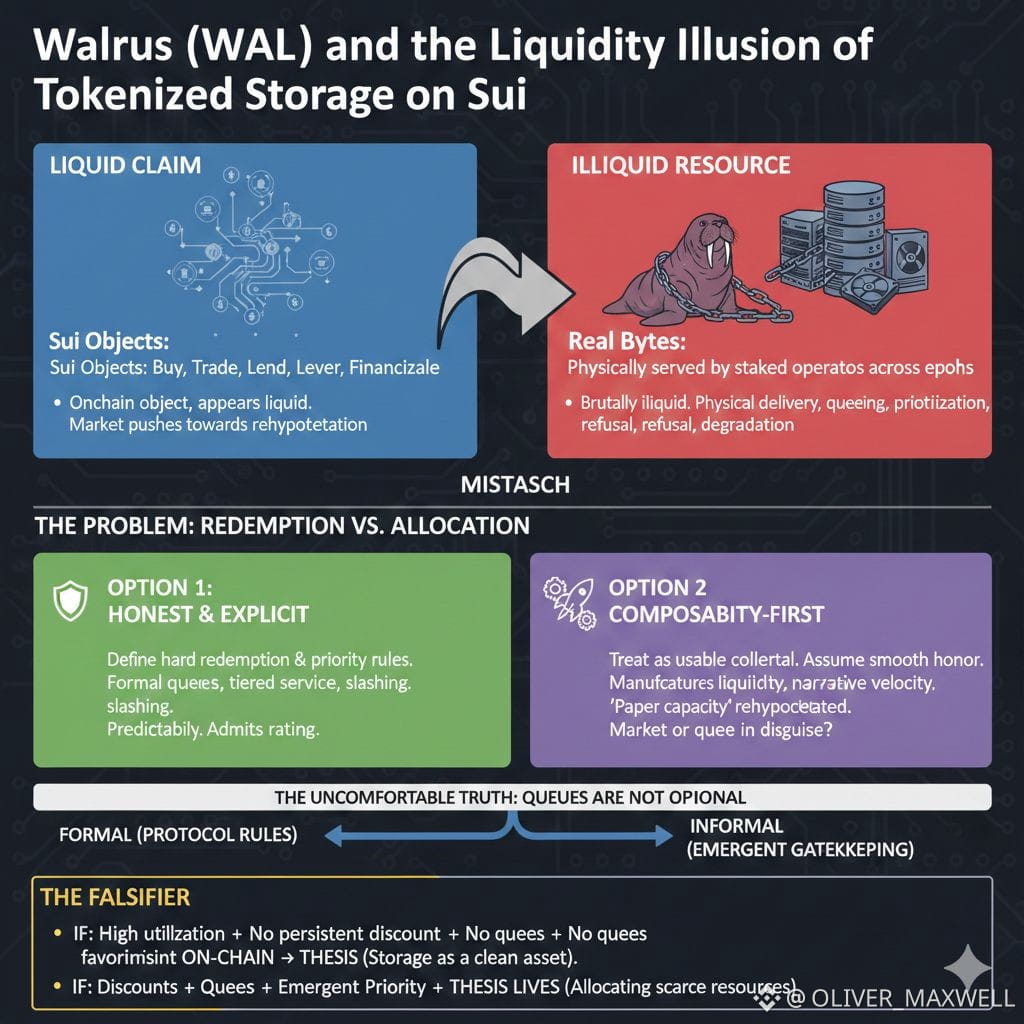

When people say “tokenized storage,” they talk as if Walrus can turn storage capacity and blobs into Sui objects that behave like a simple commodity you can financialize: buy it, trade it, lend it, lever it, and trust the market to clear. I don’t think that mental model survives contact with Walrus. Turning storage capacity and blobs into tradable objects on Sui makes the claim look liquid, but the thing you’re claiming is brutally illiquid: real bytes that must be physically served by a staked operator set across epochs. The mismatch matters, because markets will always push any liquid claim toward rehypothecation, and any system that settles physical delivery on top of that has to pick where it wants the pain to appear.

The moment capacity becomes an onchain object, it stops being “a pricing problem” and becomes a redemption problem. In calm conditions, the claim and the resource feel interchangeable, because demand is below supply and any honest operator can honor reads and writes without drama. But the first time you get sustained high utilization, the abstraction breaks into measurable friction: redemption queues, widening retrieval latency, and capacity objects trading at a discount to deliverable bytes. Physical resources don’t clear like tokens. They clear through queuing, prioritization, refusal, and, in the worst case, quiet degradation. An epoch-based, staked operator set cannot instantly spin up bandwidth, disk IO, replication overhead, and retrieval performance just because the price of a capacity object moves.

This is where I think Walrus becomes mispriced. The market wants to price “capacity objects” like clean collateral: something you can post into DeFi, borrow against, route through strategies, and treat as a stable unit of account for bytes. But the operator layer is not a passive warehouse. It is an active allocator. Across epochs, operators end up allocating what gets stored, what gets served first under load, and what gets penalized when things go wrong, either via protocol-visible rules or via emergent operational routing when constraints bind. If the claim is liquid but the allocator is human and incentive-driven, you either formalize priority and redemption rules, or you end up with emergent priority that looks suspiciously like favoritism.

Walrus ends up with a hard choice once capacity objects start living inside DeFi. Option one is to be honest and explicit: define hard redemption and priority rules that are enforceable at the protocol level. Under congestion, some writes wait, some writes pay more, some classes get served first, and the system makes that hierarchy legible. You can backstop it with slashing and measurable service obligations. That pushes Walrus toward predictability, but it’s a concession that “neutral storage markets” don’t exist once demand becomes spiky. You’re admitting that the protocol is rationing inclusion in a physical resource, not just matching bids in a frictionless market.

Option two is composability-first: treat capacity objects as broadly usable collateral and assume the operator set will smoothly honor whatever the market constructs. That’s the path that feels most bullish in the short run, because it manufactures liquidity and narrative velocity. It’s also the path where “paper capacity” gets rehypothecated. Not necessarily through fraud, but through normal market behavior: claims get layered, wrapped, lent, and optimized until the system is only stable if utilization never stays high for long. When stress hits, you discover whether your system is a market or a queue in disguise.

The uncomfortable truth is that queues are not optional; they’re just either formal or informal. If Walrus doesn’t write down the rules of scarcity, scarcity will write down the rules for Walrus. When collateralized capacity gets rehypothecated into “paper capacity” and demand spikes, the system has to resolve the mismatch as queues, latency dispersion, or informal priority. Some users will experience delays that don’t correlate cleanly with posted fees. Some blobs will “mysteriously” be more available than others. Some counterparties will get better outcomes because they can route through privileged operators, privileged relayers, or privileged relationships. Even if nobody intends it, informal priority emerges because operators are rational and because humans route around uncertainty.

That’s why I keep coming back to the “liquid claim vs illiquid resource” tension as the core of the bet. Tokenization invites leverage. Leverage invites stress tests. Stress tests force allocation decisions. Allocation decisions either become protocol rules or social power. If Walrus wants capacity objects to behave like credible storage-as-an-asset collateral on Sui, it has to choose between explicit, onchain rationing rules or emergent gatekeeping by the staked operator set under load.

This is also where the falsifier becomes clean. If Walrus can support capacity objects being widely used as collateral and heavily traded through multiple high-utilization periods, and you don’t see a persistent liquidity discount on those objects, and you don’t see redemption queues, and you don’t see any rule-visible favoritism show up on-chain, then my thesis dies. That outcome would mean Walrus found a way for a staked operator set to deliver physical storage with the kind of reliable, congestion-resistant redemption behavior that financial markets assume. That would be impressive, and it would justify the “storage as a clean asset” narrative.

But if we do see discounts, queues, or emergent priority, then the repricing won’t be about hype cycles or competitor narratives. It will be about admitting what the system actually is: a mechanism for allocating scarce physical resources under incentive pressure. And once you see it that way, the interesting questions stop being “how big is the market for decentralized storage” and become “what are the rules of redemption, who gets served first, and how honestly does the protocol admit that scarcity exists.”