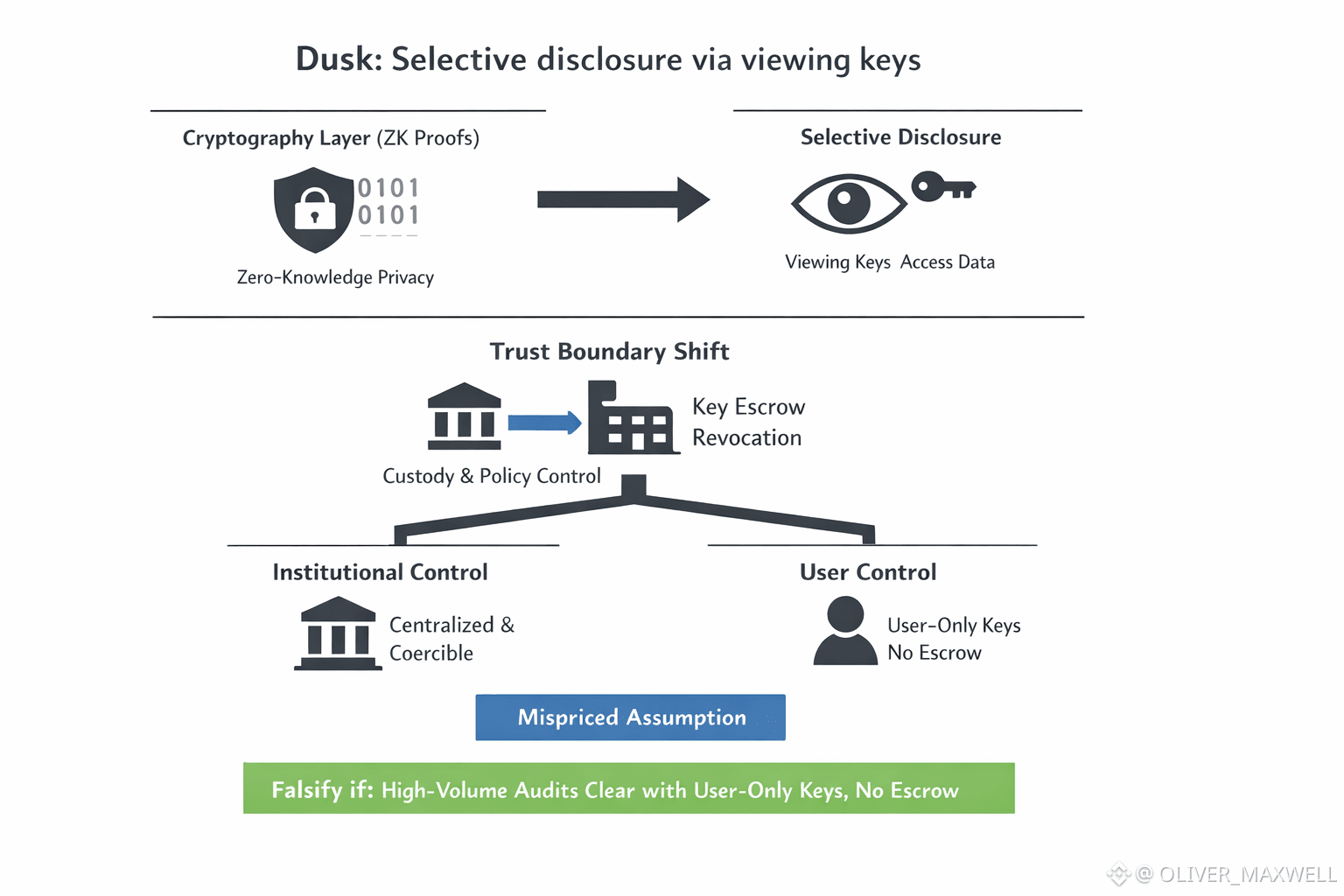

I do not think the hard part of Dusk’s regulated privacy is the zero knowledge math. On Dusk, the hard part begins the moment selective disclosure uses viewing keys, because then privacy becomes a question of key custody and policy. The chain can look perfectly private in proofs, yet in practice the deciding question is who controls the viewing keys that can make private history readable, and what rules govern their use

A shielded transaction model wins privacy by keeping validity public while keeping details hidden. Dusk tries to keep that separation while still letting authorized parties see what they are permitted to see. The mechanism that makes this possible is not another proof, it is key material and the operating workflow around it. Once viewing keys exist, privacy stops being only cryptographic and becomes operational, because someone has to issue keys, store them, control access to them, and maintain an auditable record of when they were used. The trust boundary shifts from nobody can see this without breaking the math to somebody can see this if custody and policy allow it, and if governance holds under pressure.

Institutions quietly raise the stakes. Institutional audit is not a once a year ritual, it is routine reporting, continuous controls, dispute resolution, accounting, counterparty checks, and regulator follow ups at inconvenient times. In that world, disclosure cannot hinge on a user being online or cooperative when an audit clock is running. If disclosure is required to keep operations unblocked, disclosure becomes a service level requirement. The moment disclosure becomes a service level requirement, someone will be authorized and resourced to guarantee it.

That pressure often produces the same organizational outcome under the same conditions. When audit cadence is high, when personnel churn is real, and when disclosure is treated as an operational guarantee, key custody migrates away from the individual and into a governed surface. It can look like enterprise custody, a compliance function holding decryption capability, an escrow arrangement, or a third party provider that sells audit readiness as a managed service. It tends to come with issuance processes, access controls, rotation policies, and recovery, because devices fail and people leave. Each step can be justified as operational hygiene. Taken together, they concentrate disclosure power into a small perimeter that is centralized, jurisdiction bound, and easier to compel than the chain itself.

From a market pricing perspective, this is the mispriced assumption. Dusk is often priced as if regulated privacy is mainly a cryptographic breakthrough. At institutional scale, it is mainly a governance and operational discipline problem tied to who holds viewing keys and how policy is enforced. A privacy system can be sound in math and still fail in practice if the disclosure layer becomes a honeypot. A compromised compliance workstation, a sloppy access policy, an insider threat, or a regulator mandate can expand selective disclosure from a narrow audit scope into broadly readable history. Even without malice, concentration changes behavior. If a small set of actors can decrypt large portions of activity when pressed, the system’s practical neutrality is no longer just consensus, it is control planes and the policies behind them.

The trade off is not subtle. If Dusk optimizes for frictionless institutional adoption, the easiest path is to professionalize disclosure into a managed capability. That improves audit outcomes and reliability, but it pulls privacy risk into a small, governable, attackable surface. If Dusk insists that users retain exclusive viewing key control with no escrow and no privileged revocation, then compliance becomes a coordination constraint. Auditors must accept user mediated disclosure, institutions must accept occasional delays, and the product surface has to keep audits clearing without turning decryption into a default service. The market likes to believe you can satisfy institutional comfort and preserve full user custody at the same time. That belief is where the mispricing lives.

I am not arguing that selective disclosure is bad. I am arguing that it is where privacy becomes policy and power. The chain can be engineered, but the disclosure regime will be negotiated. Once decryption capability is concentrated, it will be used more often than originally intended because it reduces operational risk and satisfies external demands. Over time the default can widen, not because the system is evil, but because the capability exists and incentives reward using it.

This thesis can fail, and it should be able to fail. It fails if Dusk sustains high volume regulated usage while end users keep exclusive control of viewing keys, with no escrow, no privileged revocation, and no hidden class of actors who can force disclosure by default, and audits still clear consistently. In practice that would require disclosure to be designed as a user controlled workflow that remains acceptable under institutional timing and assurance requirements. If that outcome holds at scale, my claim that selective disclosure inevitably concentrates decryption power is wrong.

Until I see that outcome, I treat selective disclosure via viewing keys as the real battleground on Dusk. If you want to understand whether Dusk is genuinely mispriced, do not start by asking how strong the proofs are. Start by asking where the viewing keys live, who can compel their use, how policy is enforced, and whether the system is converging toward a small governed surface that can see everything when pressured. That is where privacy either holds, or quietly collapses.