Censorship is rarely imposed by technology alone. In most systems, it is imposed by incentives. Whoever controls infrastructure decides what is served, what is delayed, and what disappears. This is true for traditional cloud storage, content delivery networks, and even many decentralised networks that quietly concentrate control over time. @Walrus 🦭/acc approaches censorship from a different angle. Instead of trying to make censorship impossible, it makes it economically irrational.

The core idea is simple: if controlling, blocking, or suppressing data costs more than serving it honestly, rational actors will choose not to censor. Walrus builds this principle into every layer of its design, turning censorship into a losing strategy.

Why Censorship Happens in Storage Networks

In centralized systems, censorship is cheap. A single operator can delete or block data with a policy change or a configuration tweak. There is no economic downside, and often political or financial upside.

In decentralized systems, censorship can still occur if control becomes concentrated. If a small group of storage providers holds most of the data, they can coordinate. They can quietly stop serving certain files. They can slow down access. They can even extort users. The more stable and long-lived their control, the easier this becomes.

Walrus eliminates this stability.

Temporary Custody Prevents Long-Term Control

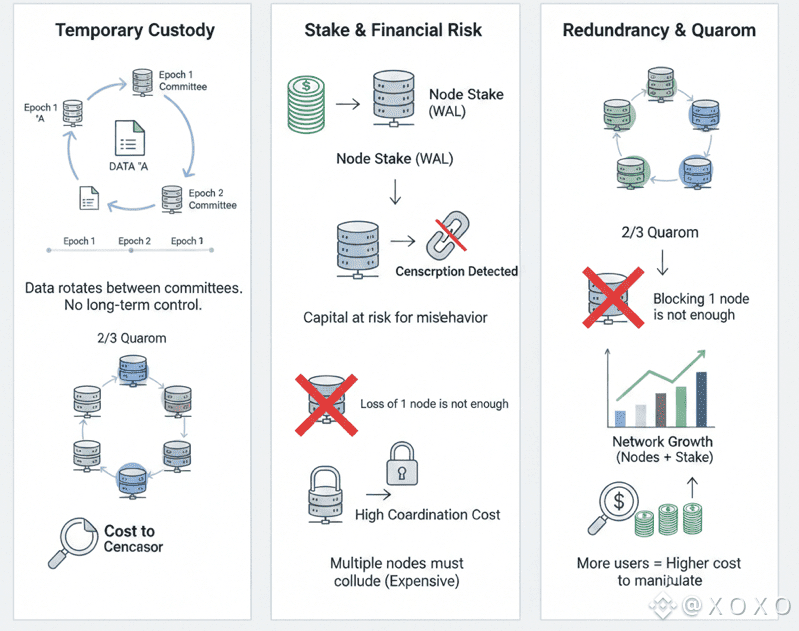

Walrus assigns data to rotating storage committees. No node holds the same data forever. Even if a group wanted to censor a file, they would only control it for a limited time. In the next epoch, that data moves to a new set of nodes.

To maintain censorship, an attacker would need to repeatedly control every committee that ever holds that data. This requires controlling a very large portion of the total stake across many unpredictable selections. The cost grows with time.

Censorship becomes a recurring expense rather than a one-time action.

Stake Turns Censorship Into Financial Risk

Nodes must stake WAL to participate in storage committees. That stake is at risk if they fail to perform their duties, including serving data when requested.

If a node refuses to serve data, it is detected through proofs and client requests. It risks losing stake and future rewards.

This means censorship is not free. Every act of suppression puts capital at risk.

Reward Cycles Punish Selective Behavior

Nodes earn rewards only if they behave correctly across an entire epoch. Selectively censoring data breaks this condition. A node that censors loses not just a single reward, but its eligibility to continue earning.

Over time, this makes censorship economically unsustainable. Honest nodes accumulate rewards. Censors are filtered out.

Redundancy and Quorum Make Blocking Ineffective

Because data is stored across multiple nodes in a committee, censoring requires coordination. Blocking one node is not enough. A censor must block a quorum.

This raises the cost dramatically. Coordinating multiple independent operators to suppress data is difficult and expensive, especially when their stake is at risk.

Growth Increases the Cost of Control

As Walrus grows, more nodes join and more stake is locked. This increases the economic weight behind every dataset. The amount of capital required to sustain censorship grows with usage.

The more valuable the network becomes, the harder it becomes to manipulate.

Walrus does not rely on goodwill to prevent censorship. It relies on economics. By making data custody temporary, requiring stake, enforcing proofs, and distributing data across committees, it ensures that censorship is not just technically difficult, but financially irrational.

That is what makes decentralized storage resilient.