Sui moves fast, but until you can store the “real world” parts of an app, images, video, audio, game maps, AI datasets, messy logs, giant configuration files, your onchain experience still feels like a showroom: beautiful, interactive, and slightly empty once people ask where everything actually lives. That’s the quiet reason @Walrus 🦭/acc matters so much to the Sui ecosystem. It doesn’t try to replace Sui or compete with it. It completes it. Sui can be the place where ownership, permissions, payments, and composable logic happen at internet speed, while Walrus becomes the place where the heavy, human-sized pieces of modern apps can exist without being forced into tiny onchain boxes.

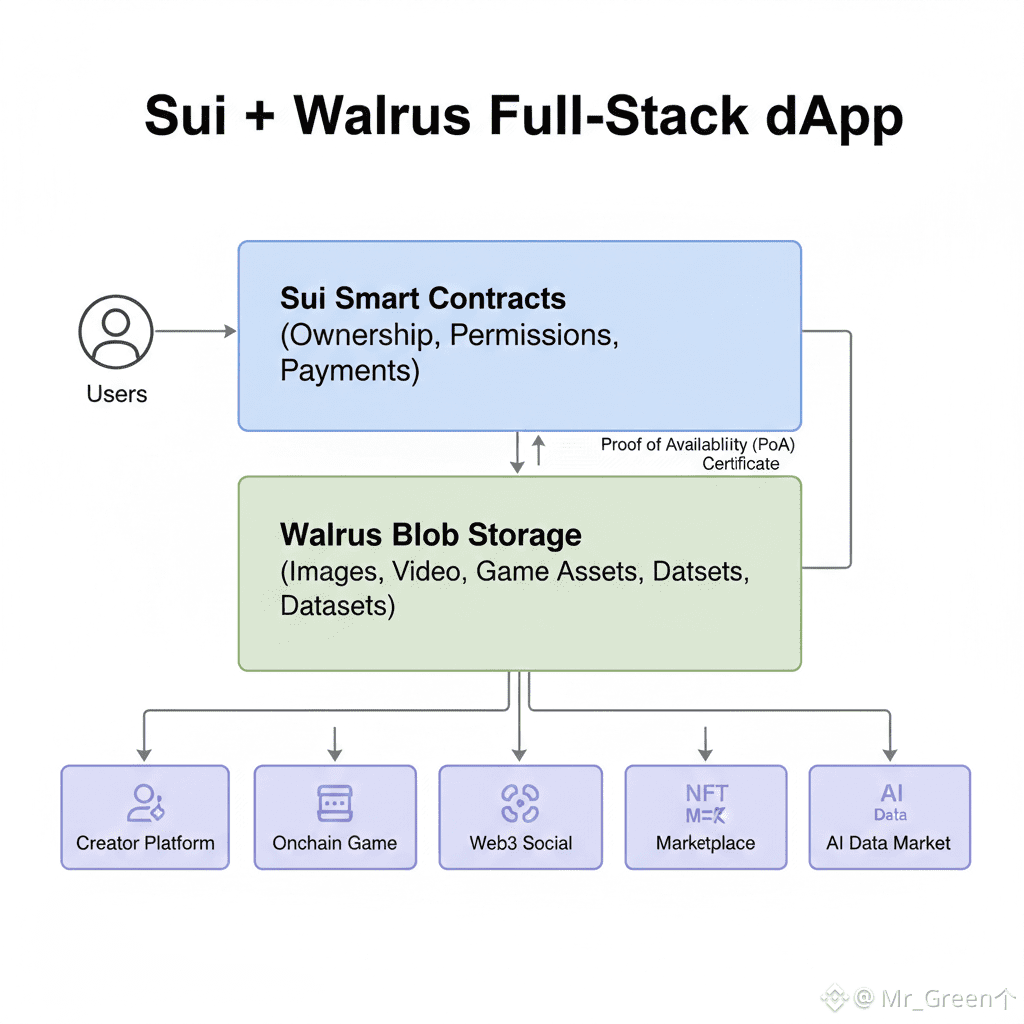

The simplest way to picture the relationship is like this: Sui is the brain that keeps track of meaning, and Walrus is the body that holds the mass. An app can mint an object on Sui that represents a piece of content, a membership, a game asset, a dataset license, or a record of provenance. That object can point to a blob stored in Walrus, and when storage is confirmed, Walrus can produce an onchain Proof of Availability certificate on Sui. Suddenly the ecosystem gets a new primitive that feels obvious in hindsight: not just “here is a link,” but “here is a verifiable receipt that this data was stored and should be retrievable for the agreed time.” That receipt-like idea changes how builders think. They stop treating storage as a best-effort external dependency and start treating it as something their smart contracts can reason about.

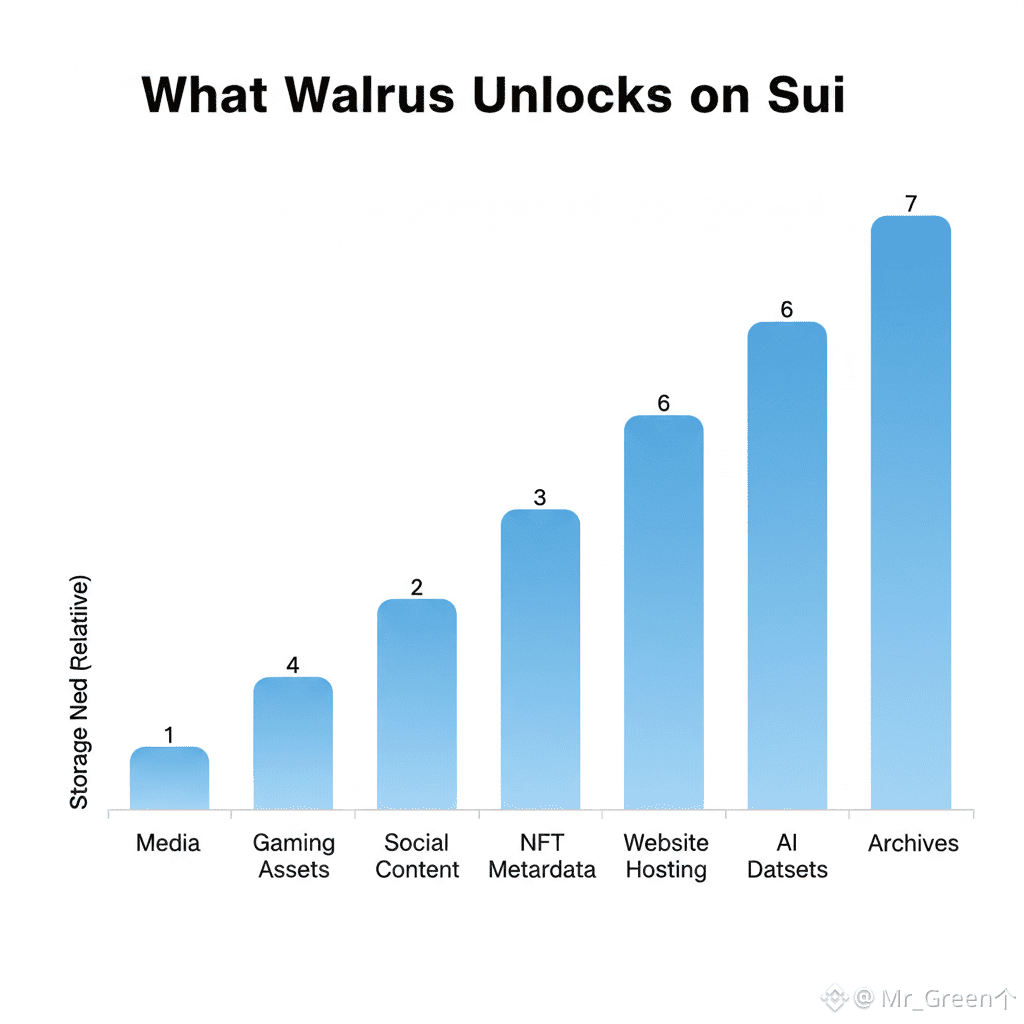

Once you have that, whole categories of applications stop being awkward and start being natural. The first category is media-first products that don’t want to pretend they’re DeFi. Imagine a creator publishing episodes, lessons, research, or art where the content itself is the product. In most crypto apps, creators sell access to a token and then route the actual files through Web2 hosting, hoping nothing breaks. In a Sui + Walrus world, the creator can sell access on Sui, subscriptions, passes, limited editions, while the actual media lives in Walrus and the app can treat “availability” like part of the business logic. It becomes possible to build a content platform where ownership and monetization are onchain, and the storage layer isn’t a hidden single point of failure.

The second category is gaming that finally behaves like gaming. Onchain games are often forced into minimalist designs because their assets don’t fit on-chain, and relying on centralized hosting undermines the promise of persistence. But games are essentially asset pipelines: textures, soundtracks, maps, replays, cosmetics, user-generated creations. With Walrus, the big assets can live in a decentralized blob store while Sui tracks who owns what, who can use what, and what gets composed together. A sword isn’t just a token ID anymore; it can be an object that points to real asset data, upgrade history, and versioned visuals. And because Sui is fast, gameplay loops don’t need to wait for slow finality just to update ownership or state.

Then there’s social. Web3 social apps often hit the same wall: the social graph might be onchain, but the posts, images, and video are somewhere else. That makes the app feel like a crypto wrapper around a traditional feed. Walrus lets Sui social products become content-native. When a post is created, the data can be stored as a blob, and the post object on Sui can reference it. That single design shift makes new experiences possible: verifiable archives of posts, portable identity tied to content, and communities that can move front ends without losing their history. It also creates a healthier developer reality. If the storage layer is designed for big files, teams don’t have to choose between “decentralized ideals” and “the app actually works.”

NFTs become less fragile too, and that’s a bigger deal than people admit. The NFT world learned the hard way that it’s not enough to own a token if the metadata and media vanish, change, or break. With Walrus, storing NFT media and metadata in a purpose-built blob layer can reduce the chance that the experience degrades into broken links. On Sui, NFTs can be rich objects with composable attributes; Walrus gives them a better home for the bytes that make the NFT feel real. That unlocks a more serious kind of digital collectible, one that’s closer to software than to a static image.

One of the most interesting shifts is what happens to websites and app front ends. If your front end lives on traditional hosting, you can still have “decentralized” contracts, but the doorway can be shut at any time. A decentralized storage layer makes it plausible to host sites and app assets in a way that’s harder to censor and easier to preserve. When the site itself becomes something that can be owned and managed through Sui objects, developers start thinking differently about publishing. A project can ship a front end that’s not just a URL, but an owned resource that can be upgraded transparently and referenced by other apps.

AI is the category everyone loves to mention, but there’s a grounded reason it fits. AI isn’t just about models; it’s about data. Datasets, embeddings, training artifacts, evaluation sets, and provenance trails are huge, and they need to be shareable, verifiable, and retrievable. Walrus offers a storage layer suited for large blobs, while Sui can manage permissions, licensing, payment splits, and provenance objects that point to those blobs. That combination can enable something practical: data products. Instead of “trust me, this dataset exists,” you can build markets where access rights are onchain and the data is stored in a network designed to keep it available.

There’s also a less glamorous but extremely important category: archives. Chains and apps produce an ocean of data that people want to keep, historical state snapshots, analytics logs, proofs, research corpuses, and community records. In many ecosystems, long-term data storage ends up in centralized services because it’s simpler. Walrus makes it easier to imagine public archives that are not dependent on a single organization. And if Sui references those archives as objects, apps can build on them like libraries, not like private databases.

What ties all these categories together is that they remove a hidden tax on builders: the constant need to stitch together a Web2 storage story with a Web3 ownership story. When storage is treated as a first-class piece of the ecosystem, builders stop spending energy on duct tape and start spending it on product design. It also changes who can build. Smaller teams can ship richer apps because they don’t need to invent a storage strategy from scratch. They can lean on a shared primitive: blobs in Walrus, meaning and ownership on Sui.

And that is why Walrus isn’t just “another protocol” in the Sui ecosystem. It’s a permissionless upgrade to what Sui can represent. Without big, reliable data, a high-performance chain mainly excels at moving small pieces of value and state around. With a blob layer next to it, Sui can host products that look like real internet applications: media platforms, games, social networks, data markets, publishing tools, archives, and experiences that feel complete rather than symbolic. Over time, that completeness compounds. More complete apps attract more users. More users justify more infrastructure. More infrastructure makes the next wave of apps easier to build.

If Sui is where the rules of the digital world are enforced, Walrus is where the world’s stuff can finally live. That’s how an ecosystem stops being “a chain with apps” and becomes something closer to a full stack, logic, ownership, and content all speaking the same language.