Walrus approaches decentralized storage with the assumption that failure, delay, and change are normal conditions rather than exceptional events. In real networks, storage nodes can crash, recover later, or miss data during writes due to asynchronous communication. The two-dimensional encoding model shown in the diagram is Walrus’s answer to this reality. Instead of demanding that every node receive its data perfectly at write time, Walrus allows incompleteness in the short term and guarantees completeness in the long term. This shift in mindset is what enables Walrus to scale without collapsing under coordination and bandwidth costs.

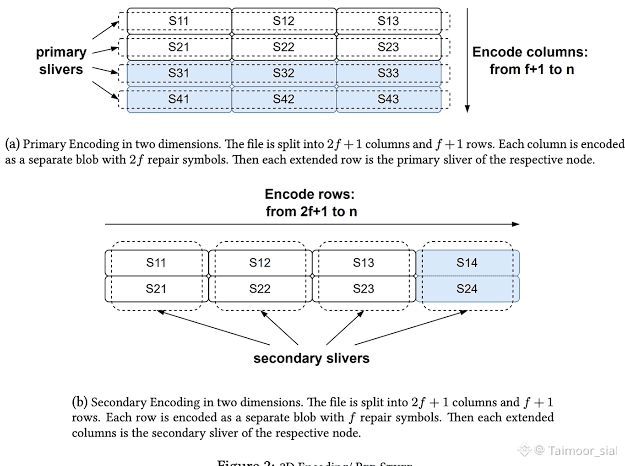

In the first phase, @Walrus 🦭/acc performs primary encoding by splitting a file into a structured grid made of rows and columns. Each column is encoded independently and extended with repair symbols, and each extended row becomes the primary sliver for a specific storage node. This means that during the write phase, nodes receive a horizontal slice of the data that spans multiple columns. Even if some nodes are slow or temporarily unavailable, the write can still complete because the protocol only requires a quorum of acknowledgements rather than full participation. Availability is proven without forcing the system into a fully synchronized state.

However, Walrus does not assume that this initial distribution is sufficient forever. Some honest nodes may miss their primary sliver entirely during the write phase. In many storage systems, this would lead to permanent imbalance or force a costly global rebuild. Walrus avoids this outcome by introducing a second encoding dimension. After primary encoding, the system performs secondary encoding across rows instead of columns. Each row is encoded as its own blob and extended horizontally, producing secondary slivers that are distributed across nodes.

The interaction between these two dimensions is what makes Walrus self-healing. Columns can be reconstructed from rows, and rows can be reconstructed from columns. If a node missed its primary sliver, it can later recover it using secondary slivers obtained from other honest nodes. This recovery process does not require rewriting the entire file or contacting every participant in the system. It is local, incremental, and proportional to the amount of missing data rather than the size of the entire blob.

Over time, this mechanism ensures that every honest storage node eventually holds its required slivers for every blob that has passed proof of availability. This property is known as completeness, and it is critical for long-term reliability. Completeness allows read requests to be evenly distributed across the network, prevents hotspots, and ensures that the system remains robust even as nodes join and leave. Instead of freezing the network to maintain consistency, #walrus allows the network to evolve while preserving correctness.

Two-dimensional encoding also makes reconfiguration practical. When storage committees change between epochs, new nodes can recover the slivers they need from the existing network rather than relying on outgoing nodes to transfer everything directly. Even if some outgoing nodes are unavailable, recovery is still possible using the encoded structure of the data. This prevents reconfiguration from becoming a race that can stall progress or permanently block an epoch from completing.

What this design ultimately achieves is a transformation of decentralized storage from a brittle system into a resilient one. Walrus does not rely on strict timing, perfect communication, or full replication. It relies on structure. By encoding data in two dimensions, Walrus allows temporary incompleteness while guaranteeing eventual correctness. Data becomes something that can heal itself as the network changes, rather than something that must be constantly rebuilt from scratch. This is the foundation that allows Walrus to function as a long-lived, scalable, and truly decentralized storage network.