Walrus is not trying to be another place where data sits. It is trying to turn data custody into something you can verify, price, automate, and audit without asking anyone for permission. That framing matters because most decentralized storage conversations still orbit around ideology, not operational reality. Walrus is built for the moment when builders and enterprises stop arguing about decentralization and start demanding service guarantees they can actually prove.

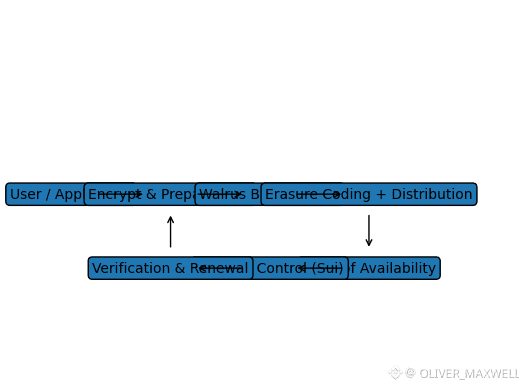

At the core is a separation most people overlook. Walrus keeps the heavy data path off chain while using Sui as a strict control plane for coordination, payment rails, and verifiable availability. Blobs and storage capacity are represented as onchain objects, so a contract can check whether a blob is available, for how long, and whether its lifetime has been renewed. That is not a cosmetic integration. It is the bridge between storage as a utility and storage as a programmable resource, where renewals, escrow, access gating, and settlement can be enforced by code rather than policy documents.

The economic and security story becomes clearer once you understand Walrus’s Proof of Availability. The writer does not just upload data and hope. They collect acknowledgements from a quorum of storage nodes and publish a certificate on Sui that becomes the official onchain record that custody has begun. After that point, storage nodes are not trusted by reputation. They are bound by an auditable obligation tied to rewards and, once fully implemented, penalties for underperformance. In practical terms, PoA turns “my data is stored” from a claim into a verifiable artifact that third parties and smart contracts can reference without needing the full blob. That property is what institutional buyers actually mean when they say compliance, audit trail, and provable service delivery.

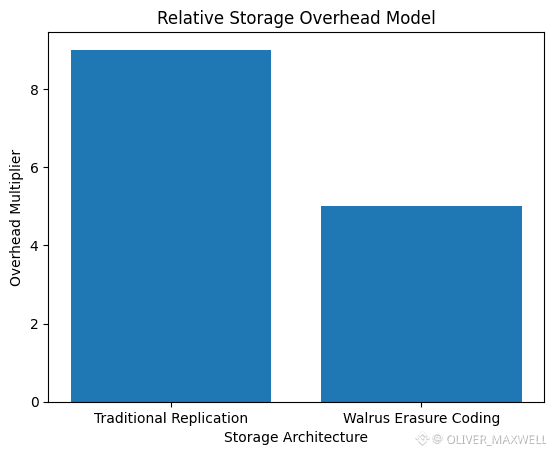

Walrus’s cost thesis is not that it is cheaper because it is decentralized. It is cheaper because it refuses to pay the replication tax that most storage networks quietly accept. Instead of full copies spread around, Walrus uses erasure coding, encoding a blob into redundant pieces that are distributed across storage nodes, with storage overhead described as roughly five times the blob size in the docs. The point is not just compression economics. It is survivability under Byzantine behavior and churn without needing every node to hold everything. The technical design is built to preserve availability even as committees rotate and network conditions change

This is where the underappreciated advantage shows up. When a network is built around proof that storage happened, you can create enforceable markets around data without building a second trust layer. A buyer can demand a blob be available for a fixed period, a contract can escrow payment until proof is present, and renewals can be automated because storage resources are objects that can be split, merged, transferred, and checked by onchain logic. You can build data workflows that look like finance workflows. That is exactly why Walrus positions itself around data markets and programmable data, not just archival storage.

Privacy is the most misunderstood part, and the honest view is more interesting than the marketing view. Walrus does not claim that blobs are natively encrypted. Blobs are public and discoverable by default, and if you need encryption or access control you secure the data before uploading. The important implication is that Walrus is aiming to be a neutral availability layer that can support confidentiality through upstream encryption and onchain access control tooling, rather than embedding a single privacy model that breaks composability. For institutions, this is often preferable. They do not want a network that promises secrecy in the abstract. They want deterministic controls, key management choices, and an auditable chain of custody. Walrus’s approach aligns with that reality, even if it is less slogan friendly.

Institutional adoption barriers in decentralized storage usually collapse into four issues. Predictability of service, provability of service, governance over change, and operational risk from unreliable operators. Walrus addresses the first two with proof of availability and onchain storage objects that define duration and availability in a way third parties can verify. It addresses governance and operational risk through staking and performance incentives that are designed to align node behavior with long term reliability, including slashing for low performance and partial fee burning. That means performance is not just encouraged. It becomes economically enforced, and the enforcement itself can be made legible to the market.

WAL token design reinforces the idea that Walrus is trying to industrialize storage economics rather than gamify attention. Max supply is defined at five billion WAL, with an initial circulating supply of one point two five billion. Distribution is structured with a large community reserve unlocking over time, user drops that are fully unlocked, subsidies that unlock linearly to support node payments as the fee base grows, and multi year schedules for contributors and early backers. The detail that matters is not the percentages by themselves. It is the explicit acknowledgement that early fee markets are thin, so the protocol plans for a subsidy runway to avoid the classic failure mode where storage networks chase unsustainably high rewards and then collapse when emissions fade.

From a builder’s perspective, Walrus is easiest to understand through workflows, not slogans. A developer acquires storage resources, stores a blob, and ends with an onchain certificate that a contract can reference. WAL is used to pay for storage, while Sui is used for transaction fees in the control plane interactions. This matters for product design because it forces teams to think in two ledgers. One for computation and coordination, one for storage service. When you design like that, you can create applications where large content is off chain but still behaves like an onchain object from the standpoint of ownership, verification, and automation.

Real use cases follow naturally once you accept that the differentiator is programmability around availability. Decentralized websites are a concrete example where site assets are stored as blobs while ownership and metadata live onchain, removing the single operator failure that makes hosting politically and operationally fragile. For media and creator tooling, proof of availability enables verifiable publishing where audiences and integrators can check that content referenced by an application is actually retrievable. For data intensive applications such as AI datasets and agent workflows, the value is not only storage capacity but data governance, where access gating and provenance can be expressed in onchain terms rather than private contracts. Even in DeFi adjacent designs, the role is not to store transactions, but to make high value inputs and evidence retrievable and verifiable on demand, which is how you reduce fraud surfaces in systems that rely on external artifacts.

The forward looking bet is that the next wave of infrastructure competition will not be fought on raw throughput or raw price per gigabyte. It will be fought on whether data can be treated as a first class asset with enforceable guarantees. Walrus is positioning itself precisely at that junction. Its thesis is that availability proofs, erasure coded storage, and an onchain control plane together can create a storage market where reliability is measurable, obligations are enforceable, and integrations are composable. If that thesis holds, the WAL token becomes less about speculation and more about underwriting a service economy, where staking expresses risk, rewards express demand, and slashing expresses accountability. The projects that win that era will be the ones that make trust legible. Walrus is building in that direction.