Decentralized storage has historically been treated as an auxiliary concern in crypto systems rather than a foundational market primitive. While blockchains excel at settlement, ownership, and coordination, much of the value they reference depends on data that remains off‑chain: order‑book snapshots, oracle histories, AI training datasets, NFT media, audit trails, legal documentation, and metadata that gives tokenized assets real‑world meaning. This structural mismatch has left crypto markets dependent on centralized storage providers, creating fragility at the very layer where permanence and integrity matter most.

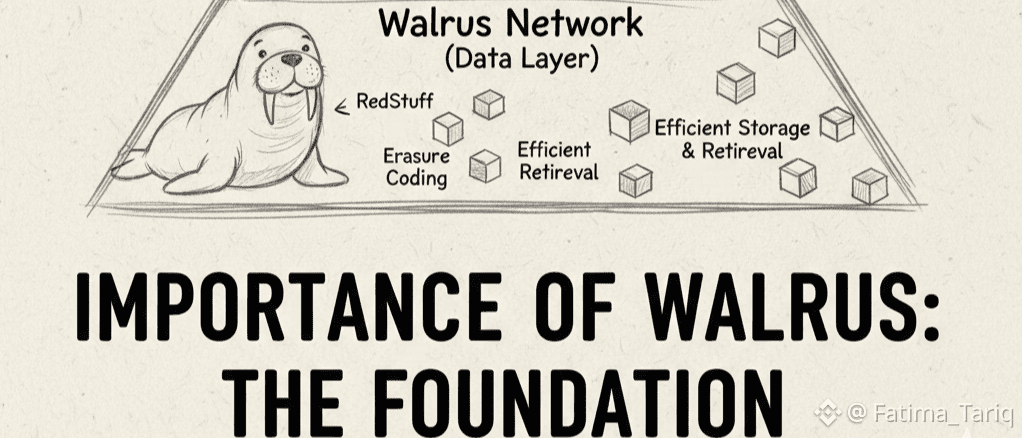

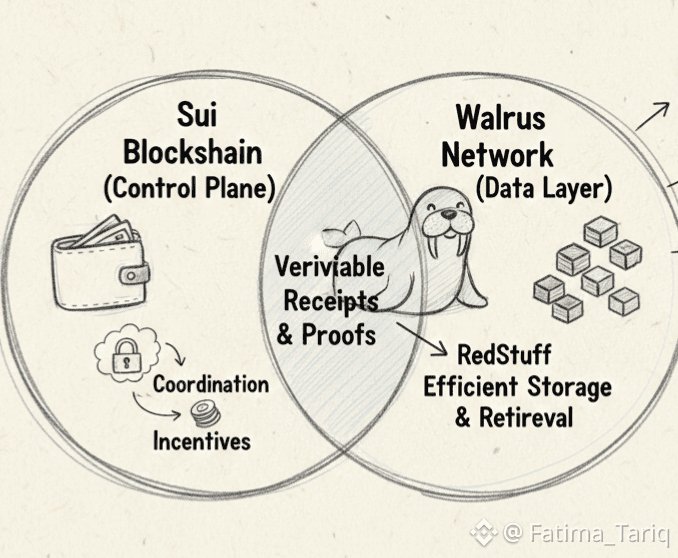

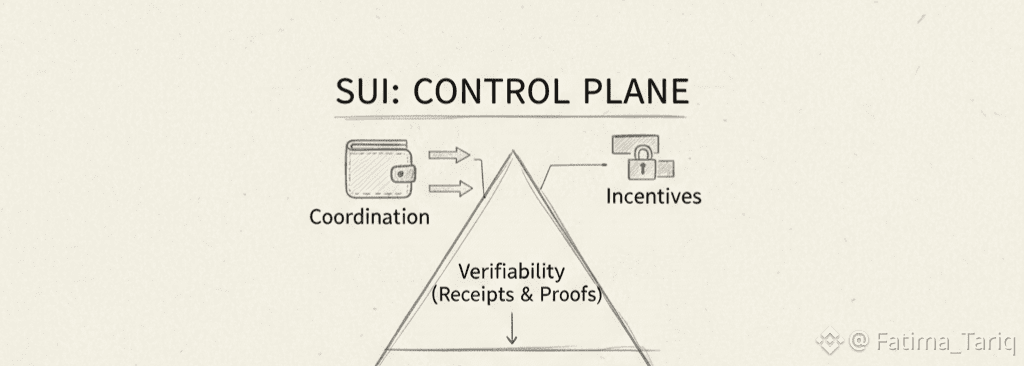

Walrus emerges as a response to this gap, not by reframing decentralization as ideology, but by attempting to industrialize decentralized storage. Introduced publicly by Mysten Labs in mid‑2024, Walrus is a decentralized storage and data availability protocol purpose‑built for large binary files (“blobs”). Instead of operating as a standalone blockchain, Walrus uses the Sui blockchain as a control plane, relying on it for blob lifecycle management, coordination, incentives, and verifiable receipts, while dedicating the Walrus network itself to efficient storage and retrieval at scale.

This separation of concerns is central to Walrus’s thesis. Sui governs rules, payments, and proofs, while Walrus focuses on the operational realities of distributed storage. From an infrastructure perspective, this mirrors how traditional systems separate control logic from data layers. For investors and builders, the implication is that Walrus is not competing with execution chains, but positioning itself as a complementary layer that can be referenced by applications, smart contracts, and agents that require durable and verifiable data availability.

The core technical innovation underpinning Walrus is its erasure‑coding design known as RedStuff, a two‑dimensional erasure coding scheme described in Walrus research publications. Unlike naive replication models, which store full copies of data across many nodes at high cost, RedStuff fragments blobs into encoded pieces distributed across storage nodes. As long as a sufficient subset of these pieces remains available, the original data can be reconstructed. Research claims indicate resilience with storage overhead in the ~4.5x to ~5x range, while enabling recovery bandwidth proportional to lost data rather than requiring full re‑downloads.

This design choice directly impacts economic viability. Storage markets are unforgiving: if decentralized storage is too expensive, it relies on subsidies and ideology; if it is unreliable, serious applications avoid it entirely. Walrus documentation explicitly frames cost efficiency as a design goal, with encoded fragments distributed across nodes rather than full replication everywhere. This positions Walrus closer to infrastructure economics than experimental networks, where long‑term sustainability depends on predictable cost curves rather than speculative incentives.

Operational transparency is another defining feature. Walrus documentation acknowledges that writing and reading blobs involves substantial distributed coordination, often requiring thousands of requests to write and hundreds to read, depending on access patterns. Rather than obscuring this complexity, the project surfaces it, signaling that real distributed work is being performed beneath the abstraction layer. For builders, this honesty matters, because it shapes how applications are architected and where tooling improvements are needed for adoption.

The shift from vision to reality became tangible with Walrus’s mainnet launch on March 27, 2025. At this point, storage guarantees moved from theoretical to operational. Mainnet deployment exposed the system to real‑world variables such as node churn, retrieval latency, and cost behavior under load. In decentralized infrastructure, this transition is often more informative than whitepapers, because it reveals which assumptions survive contact with production conditions.

The most consequential feature for market formation is verifiability. Walrus introduces the concept of on‑chain Proofs of Availability, generated through Sui interactions that certify a blob’s existence and availability over time. This transforms storage from a claim into a verifiable state. For markets, this distinction is critical: traders and applications price certainty, not capacity. Data that can be proven to exist and remain accessible becomes usable as an input to financial workflows, smart contracts, and automated agents.

This is where decentralized data markets become plausible rather than aspirational. A functional data market requires more than upload and download. It requires guarantees around persistence, permissioning for private datasets, composability with applications, and settlement mechanisms for data rights. Walrus’s architecture allows datasets to be referenced, verified, and integrated into workflows without trusting a centralized storage provider. This opens use cases ranging from AI datasets and DeFi risk models to tokenized RWA documentation and persistent game assets.

From a long‑term perspective, Walrus is not positioned for explosive short‑term adoption. Storage infrastructure tends to grow slowly and quietly, driven by developers integrating it because it works rather than users speculating on narratives. However, if Walrus succeeds in delivering cheap, resilient, and verifiable blob storage at scale, it becomes deeply embedded infrastructure. Storage creates switching costs, because it holds history. Once applications depend on it, demand becomes structural rather than cyclical, turning decentralized data markets from a slogan into a durable sector.

#Walrus #LearnWithFatima $WAL @Walrus 🦭/acc #BinanceSquareTalks #BinanceSquareFamily #creatorpad