Walrus was not built around the idea that storage needs to be fast at all costs. It was built around the quieter assumption that storage needs to be dependable even when nothing else is. That single design instinct explains most of the system’s behavior once you look closely.

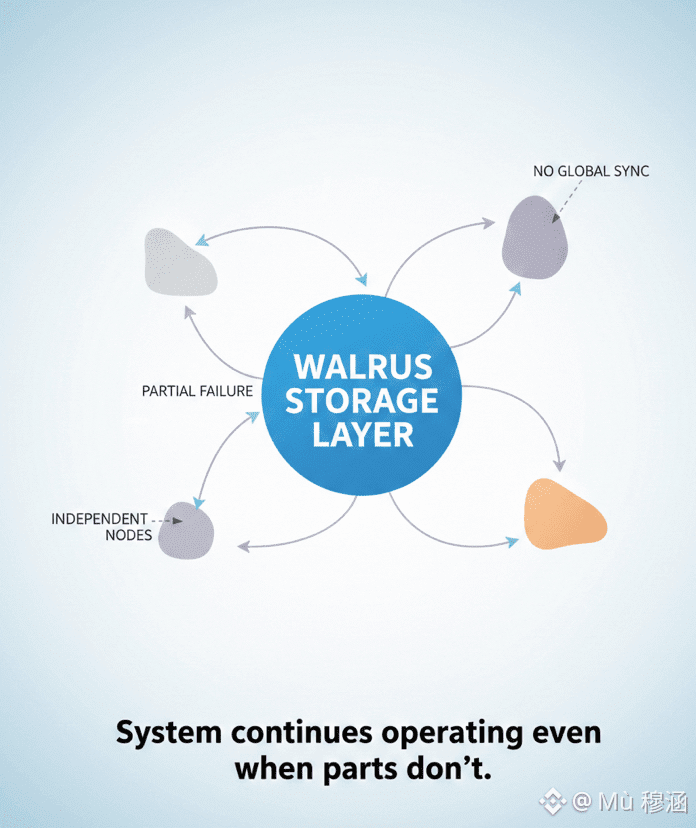

At its core, Walrus treats data as something that should survive stress, imbalance, and partial failure without constantly asking the network to coordinate itself. Many systems try to solve reliability by increasing coordination. More checks, more confirmations, more global awareness. Walrus goes the opposite way. It limits how much any part of the system needs to know about the rest. That choice shapes its scalability in a very specific way.

When data enters Walrus, it is not treated like a live object that must be constantly watched. It becomes a stored artifact with clear expectations about availability and recovery. The system assumes that some storage providers will be slow, some will disappear, and some will behave inconsistently. Instead of fighting that reality, Walrus designs around it. Reliability is not achieved by perfection, but by tolerance.

This tolerance is where scalability quietly emerges. Because Walrus does not require every storage node to be tightly synchronized, the network can grow without creating bottlenecks of coordination. Nodes can join and leave without triggering expensive global reshuffling. Storage capacity scales horizontally, but more importantly, operational complexity scales slowly. That matters more over time.

There is a cost to this approach. Walrus accepts that retrieval is not always instantaneous. In some cases, accessing data may involve waiting for slower components to respond or reconstructing from partial availability. This is not a flaw. It is an explicit trade-off. Walrus prioritizes certainty of retrieval over speed of retrieval. In institutional contexts, that distinction is important.

Another design choice worth noticing is how Walrus separates storage responsibility from performance optimization. The system does not assume that every node should be optimized or even well-resourced. It assumes heterogeneity. Some nodes are strong, others are weak. Walrus does not punish weaker participants by excluding them. Instead, it designs storage logic that remains stable despite uneven performance. This allows the network to absorb real-world conditions without constant rebalancing.

Quality, in Walrus, is measured less by benchmarks and more by predictability. Data behaves the same way over time. It does not degrade as the network grows. It does not require increasingly complex operational oversight. The system stays legible even as it expands. That is a form of quality that is often overlooked.

Scalability here is not just about size. It is about maintaining behavior under growth. Walrus does not promise that adding more users makes everything faster. It promises that adding more users does not make things fragile. That promise shapes how institutions think about long-term storage commitments.

One intentional limitation in Walrus is that it avoids dynamic optimization during retrieval. The system does not constantly chase the fastest possible path. It follows predefined recovery logic that is stable and boring by design. This can feel inefficient in ideal conditions. But under stress, boring systems tend to outperform clever ones.

There is also a quiet discipline in how Walrus handles failure. Failures are not treated as emergencies that must be resolved immediately. They are treated as expected events that the system already knows how to absorb. This reduces operational noise and avoids cascading reactions that often damage otherwise healthy networks.

Over time, this design leads to a particular kind of reliability. Not the dramatic kind that advertises uptime metrics, but the slow, institutional kind where systems simply continue to function year after year without drawing attention to themselves. Walrus feels designed for that future rather than for short-term performance narratives.

And that is perhaps the most revealing thing about it. Walrus does not optimize for moments. It optimizes for decades. The system is comfortable being slightly slower, slightly heavier, and slightly less flexible if that buys stability under growth. Not every use case needs that. But the ones that do usually know it early.

So when people talk about Walrus scalability, they often miss the point. It does not scale by pushing harder. It scales by asking less of each component. And when reliability is discussed, it is not framed as uptime, but as the confidence that data will still be there when conditions are no longer friendly.

That perspective may not excite everyone. But for systems that are meant to outlive trends, it is often the only one that matters.