@Walrus 🦭/acc The easiest way to understand why reliability is back in the spotlight is to picture something simple: a file you care about, saved somewhere “safe,” suddenly refusing to load. No drama, just a blank space where certainty used to be. That kind of failure used to feel like a personal problem—an old laptop, a dying drive. Lately it feels more structural. We’ve made things efficient and linked up, but the downside is a small failure doesn’t always stay contained anymore.

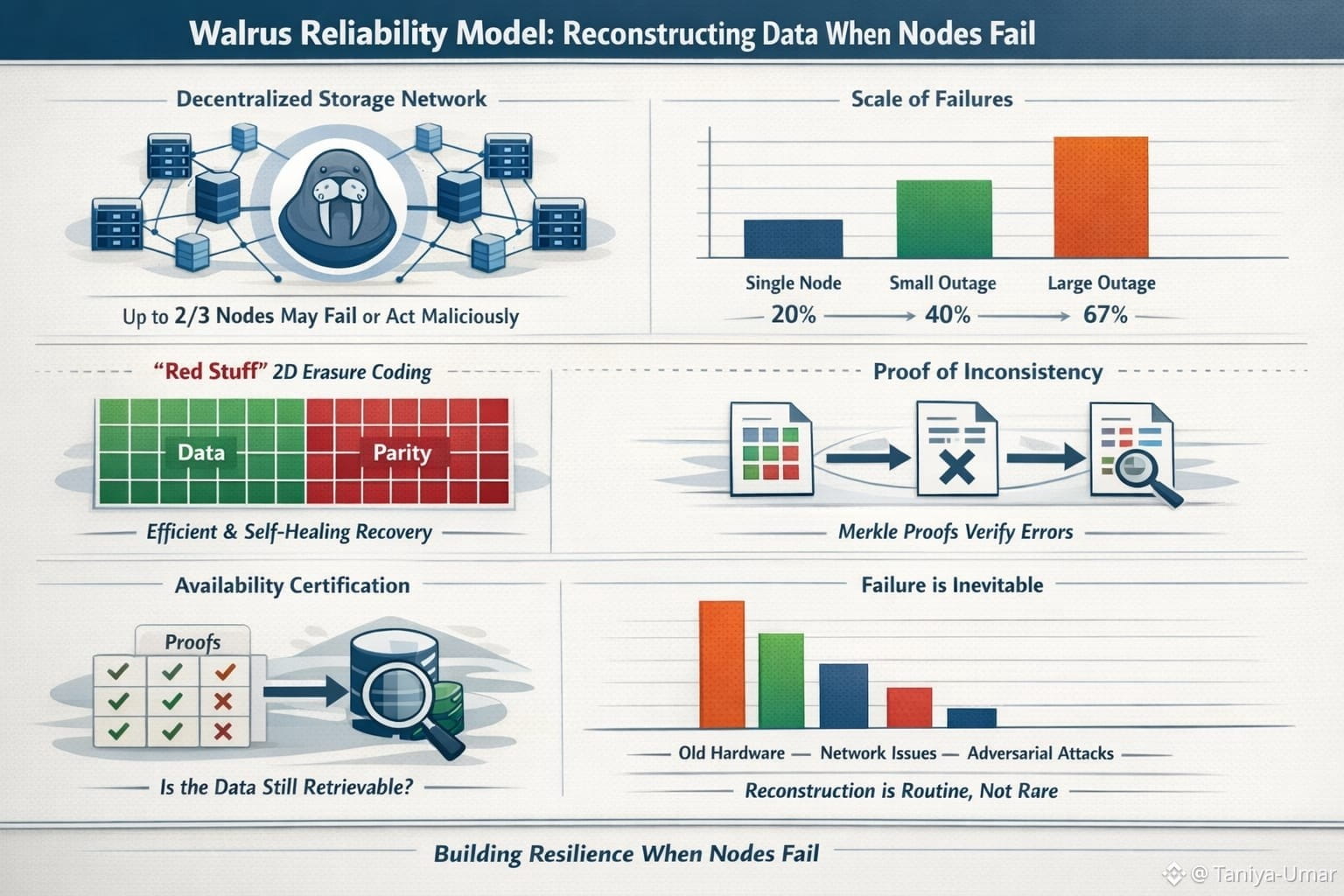

That’s where the Walrus protocol has started to show up in conversations about resilience. Walrus is a decentralized storage and data availability network designed to keep large “blobs” of data retrievable even when a lot of the underlying storage nodes fail—or don’t behave honestly. Mysten Labs describes a core guarantee that’s hard to ignore: data recovery should still be possible even if up to two-thirds of the storage nodes crash or come under adversarial control. If you’ve spent any time around distributed systems, you know how bold that sounds at first. But it isn’t magic. It’s a very specific kind of engineering discipline: assume nodes will disappear, assume some will lie, and make reconstruction the normal path rather than the emergency plan.

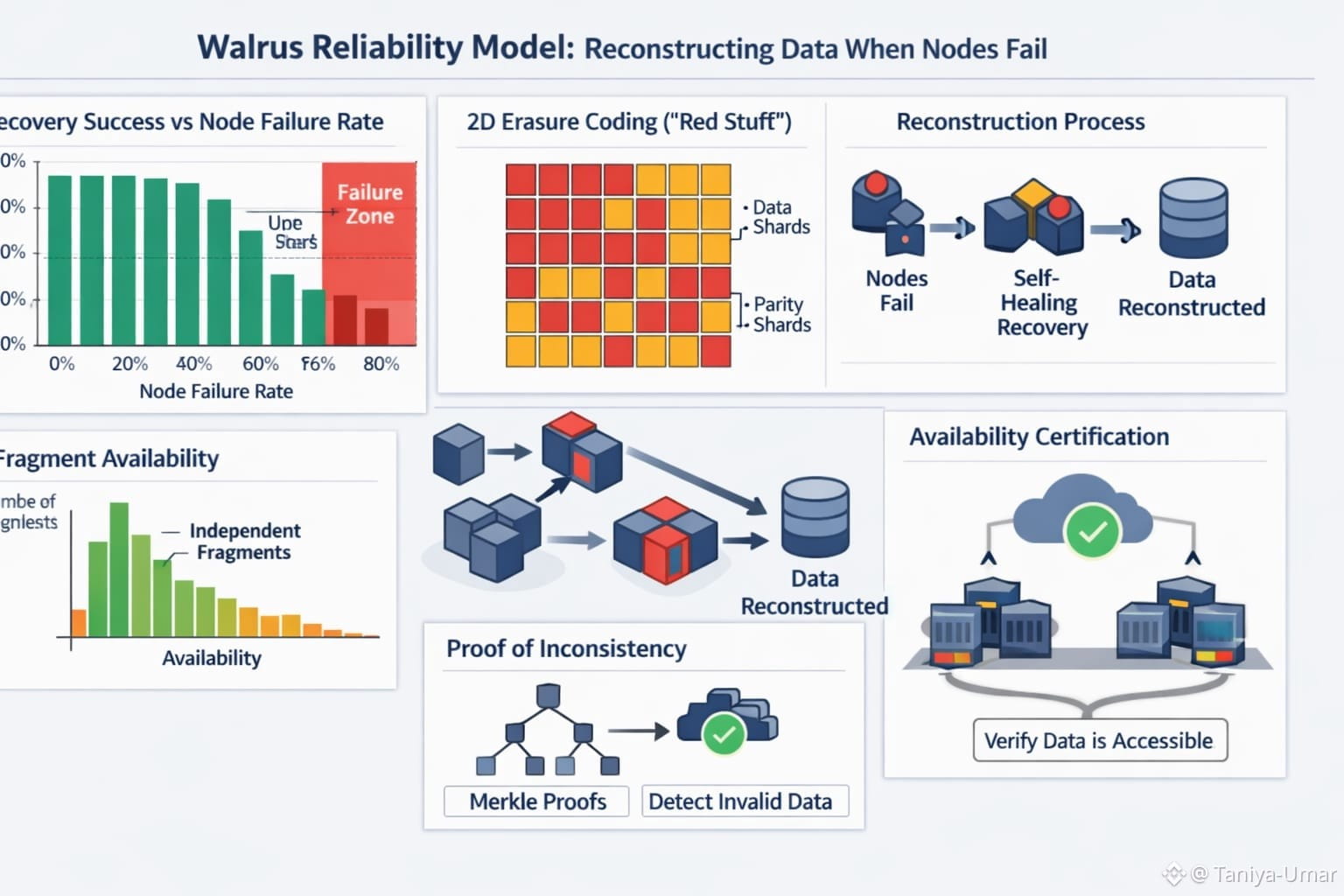

Walrus leans heavily on erasure coding, but the interesting part is how it’s tuned for a decentralized setting. In the Walrus research paper, the authors introduce “Red Stuff,” a two-dimensional erasure coding approach meant to reduce the storage overhead you’d get from simple replication, while still supporting self-healing recovery when pieces are lost. The point of splitting data into coded fragments isn’t novelty—it’s practicality. When nodes fail, you don’t want to hunt for the one “authoritative” copy. You want enough independent fragments floating around that rebuilding is routine.

What makes Walrus feel especially relevant to the title—reconstructing data when nodes fail—is that it talks openly about what happens when reconstruction doesn’t line up. The Walrus whitepaper describes a “proof of inconsistency,” where a storage node can share the specific symbols it received for recovery along with Merkle proofs, so others can verify that something has gone wrong. Instead of crossing our fingers that every node plays nice, the protocol assumes they won’t—and builds in a way to catch it. Reliability isn’t “nothing ever breaks.” It’s “when something breaks, we can show exactly what happened.” Reliability, here, isn’t just “it works.” It’s “we can prove what happened when it didn’t.”

So why is this trending now, instead of five years ago? Part of it is scale. AI workloads, richer media, and always-on apps push more data through more layers, and each layer adds its own failure modes. Part of it is also the public nature of outages. When Cloudflare had its November 18, 2025 outage, the story wasn’t about a dramatic attack. It was a chain reaction sparked by a database permission change that caused a configuration “feature file” to double in size, eventually crashing critical routing software. That kind of incident lands differently today because we’ve all felt the blast radius—services you didn’t even realize depended on the same infrastructure suddenly wobble at once.

Decentralized storage adds another pressure: you can’t assume a single operator will always be reachable, neutral, or aligned with your incentives. Blockchains and onchain apps keep running even when individual participants drop out, but that only works if the data those apps need is still available. That’s why Walrus frames “availability certification” as part of the problem, not an afterthought: it’s not enough that data exists somewhere; you need a way to check that it’s still retrievable without downloading everything.

What I find grounding about this whole direction is that it treats failure as ordinary. Not tragic, not rare—just ordinary. Walrus isn’t promising a world where nodes never fail. It’s trying to make sure that when they do, reconstruction feels boring. And honestly, boring is the goal.