@Vanar Most people don’t wake up wanting a new chain, a new wallet, or a new set of rituals for moving value online. They want an app that works, and they want it to feel boring in the best way. When crypto products ask newcomers to copy a seed phrase, hunt for a gas token, and decode “wrong network” pop-ups, the problem isn’t only complexity. It’s the message underneath: this was built for insiders, and you’re visiting their world, not yours.

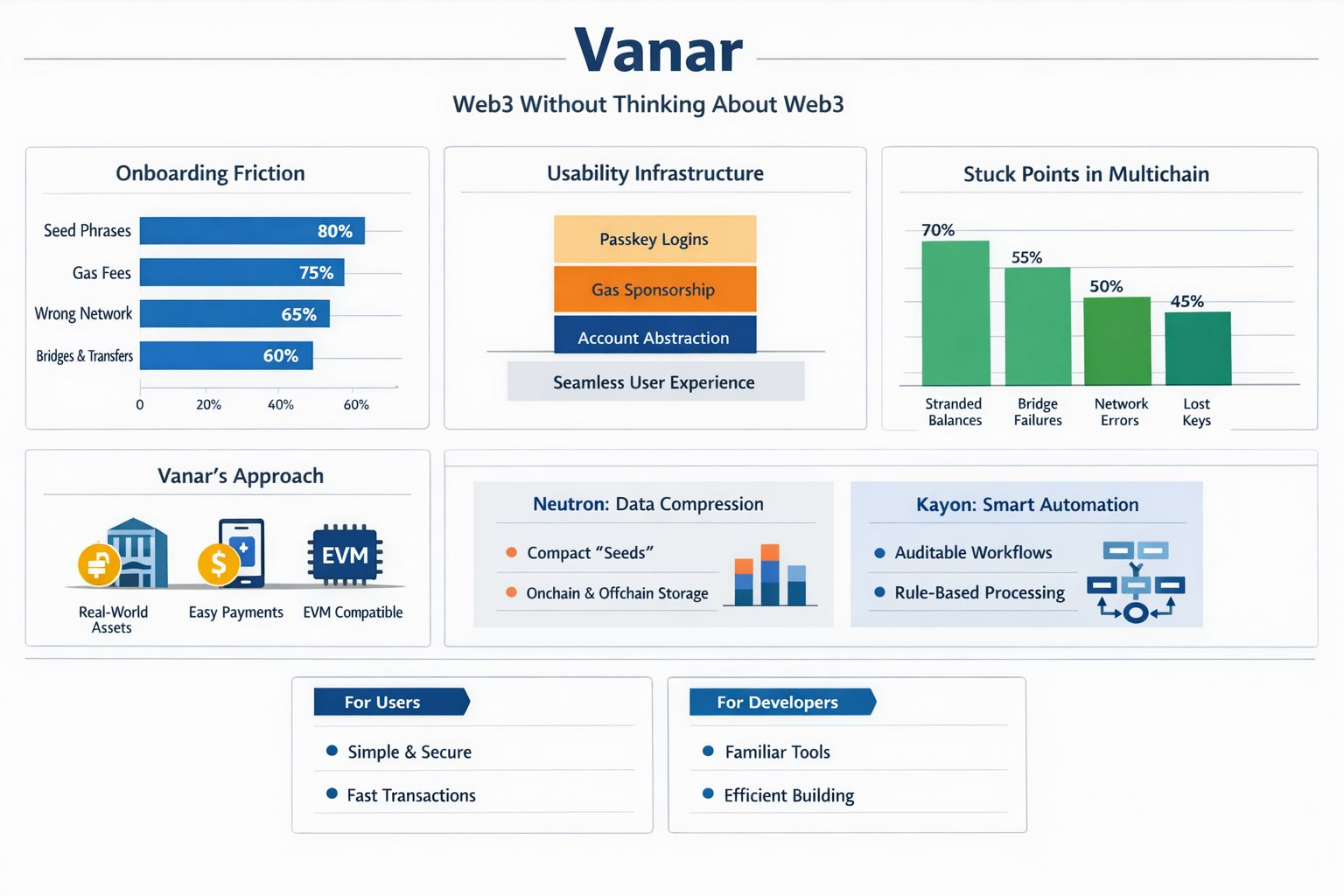

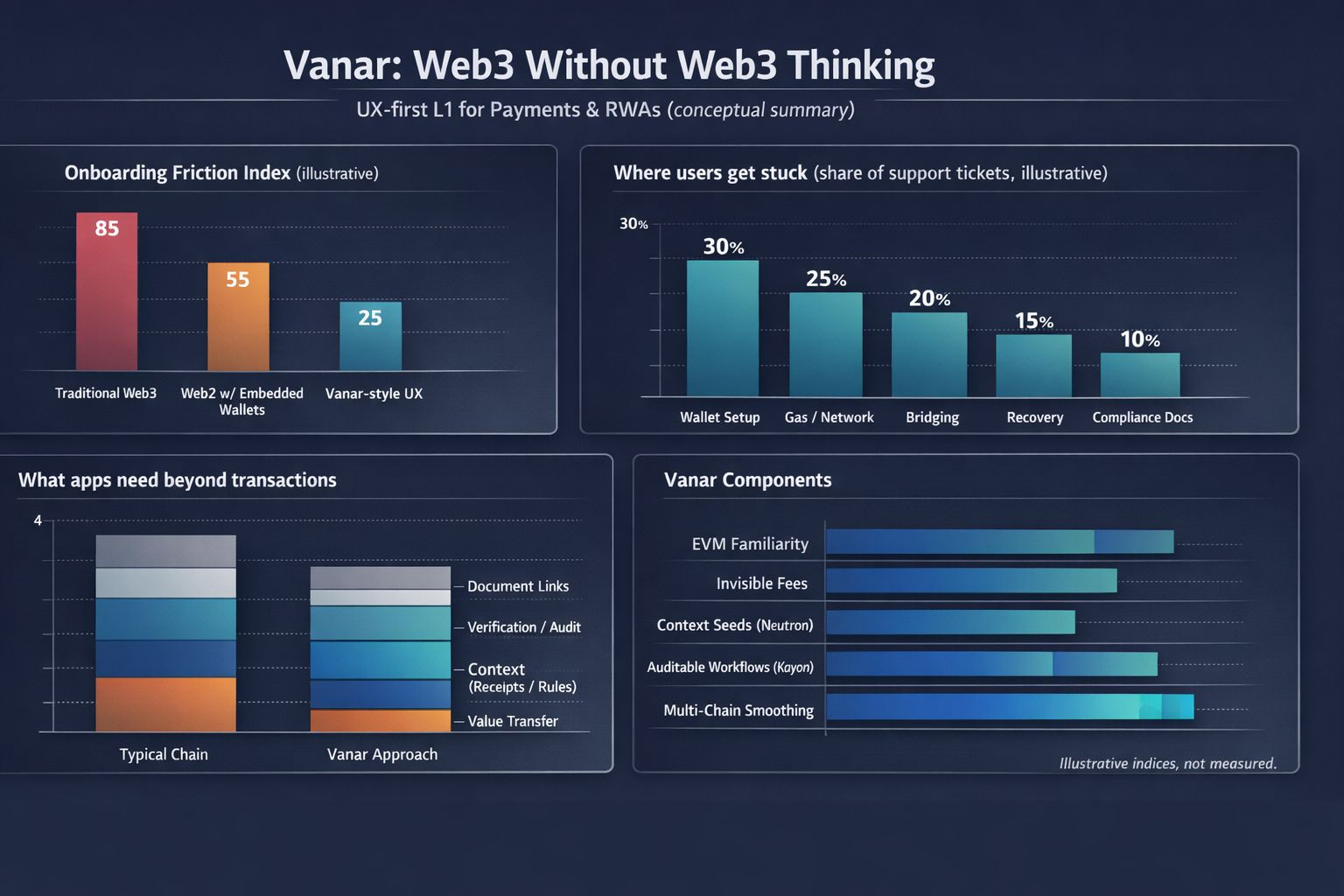

That’s why the idea of “Web3 without thinking about Web3” has become a serious design target in 2025 and 2026. The industry has started treating usability as infrastructure, not a coat of paint. Account abstraction, gas sponsorship, and passkey-style logins aren’t glamorous, but they change what a “normal” onboarding flow can look like. The multi-chain world expanded what builders could do, but it also expanded the number of ways users can get stuck. Balances scattered across networks, bridges that add stress instead of convenience, and that lingering worry that a single misclick could turn into a permanent loss. People didn’t sign up to be their own IT department just to send a payment.

Vanar is relevant in this exact gap because it’s trying to make the machinery less visible, not more celebrated. It positions itself as a Layer 1 built for payments and tokenized real-world assets, which is a revealing choice. Payments and RWAs aren’t hobby use cases; they’re domains where the tolerance for weirdness is extremely low. If a collectible breaks, it’s annoying. If a payout fails or an invoice can’t be verified, it becomes a support ticket, a compliance problem, or a business dispute. In that world, “don’t make me think” isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the difference between a product people adopt and one they abandon after the first confusing screen.

What makes Vanar’s pitch feel aligned with the title is its emphasis on what everyday applications actually need: not just transactions, but context. A payment isn’t only a value transfer; it comes with references, receipts, and rules. A tokenized asset isn’t only a token; it’s tied to documents, provenance, and obligations that live outside the chain. When that context sits off to the side as loose files and database entries, the “Web3 part” becomes an awkward bolt-on, and users still end up depending on a trusted middleman to make sense of it all. Vanar’s bet is that more of that context can be handled in a way that keeps the user experience calm while still leaving a trail that can be checked later.

There’s also a practical restraint in how Vanar approaches developers, and that matters more than it sounds. It leans into familiarity with an EVM-compatible environment rather than forcing teams to relearn the basics. That choice isn’t flashy, but it can reduce the number of sharp edges that end users eventually feel. When teams aren’t spending months wrestling exotic tooling, they have more room to get the human parts right: onboarding, recovery, customer support, and the many small decisions that decide whether an app feels intuitive or hostile.

Vanar’s more distinctive argument is around data and interpretation, where the title’s promise becomes concrete. Neutron is presented as a way to compress and structure information into smaller “Seeds” that can be referenced and verified. The headline claims around compression are easy to treat cautiously, but the grounded idea is easier to appreciate: consumer-grade apps need to handle documents and proofs without turning users into archivists. A hybrid approach—fast storage where it makes sense, with verification hooks when it matters—can be a realistic compromise if it’s implemented clearly. The user shouldn’t have to learn the difference between onchain and offchain storage; they should be able to submit what’s needed once, know it can be validated later, and move on.

Kayon is described as the next step: a reasoning layer meant to work with those Seeds and external datasets to produce auditable workflows. The “AI” label is where skepticism is healthy, especially in anything that touches finance. Intelligence isn’t the same thing as reliability, and automated systems only earn trust when they behave predictably, log their steps, and fail in ways that are legible. Still, there’s a grounded version of this ambition that matches the real world: if a system can help applications interpret rules, match documents to actions, and preserve an audit trail, then users may never have to see the complexity that businesses currently manage.