If you are new to crypto and someone mentions a high performance Layer 1, the first instinct is usually to check the chart. Is it trending? Is volume rising? But performance blockchains are not just price stories. They are engineering systems. So instead of starting with hype, it is more useful to start with one simple question: does this network actually perform well when tested under real world conditions?

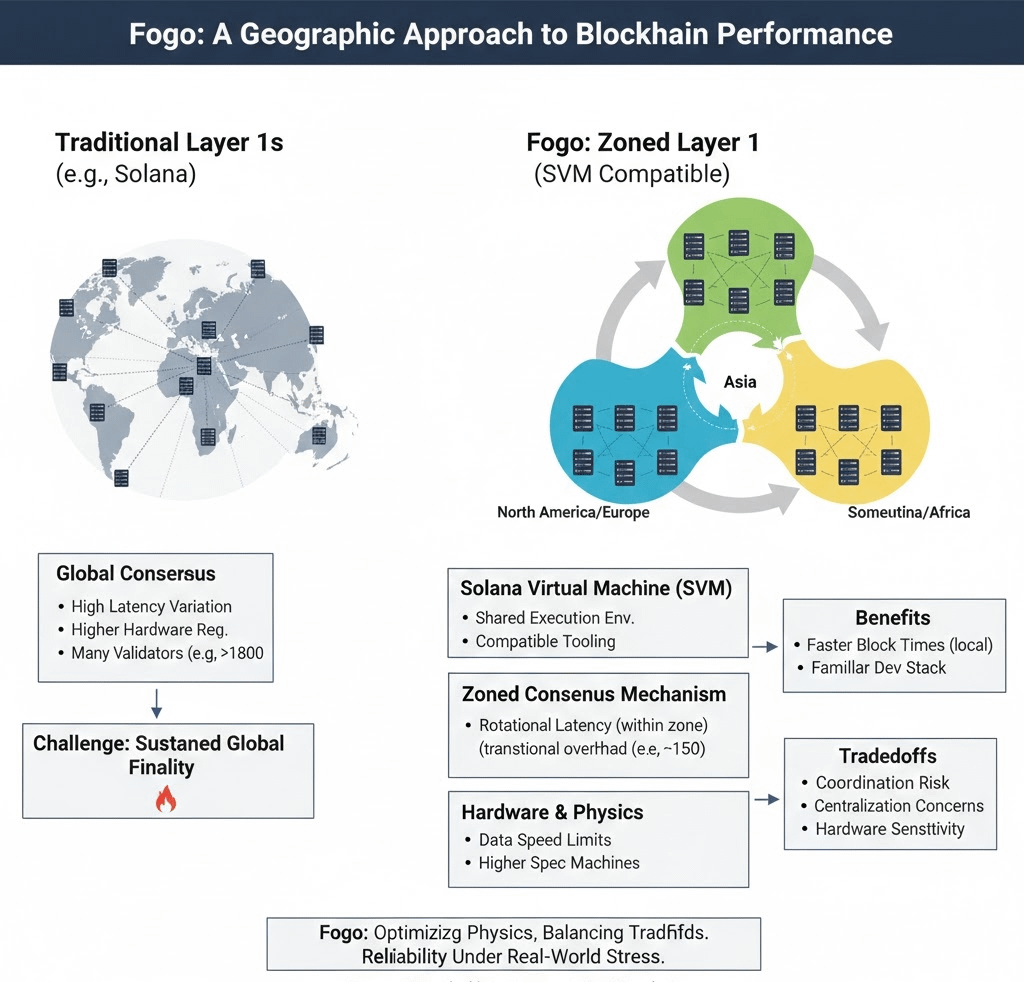

Fogo is built on the Solana Virtual Machine, which means it uses the same smart contract execution environment as Solana. That makes it compatible with existing Solana tools and applications. But compatibility alone does not explain why it exists. Fogo’s core idea is that blockchain speed is not only a software issue. It is a geography and hardware issue. Data moves at limited speed across the globe. Validators are physical machines. Physics applies whether we like it or not.

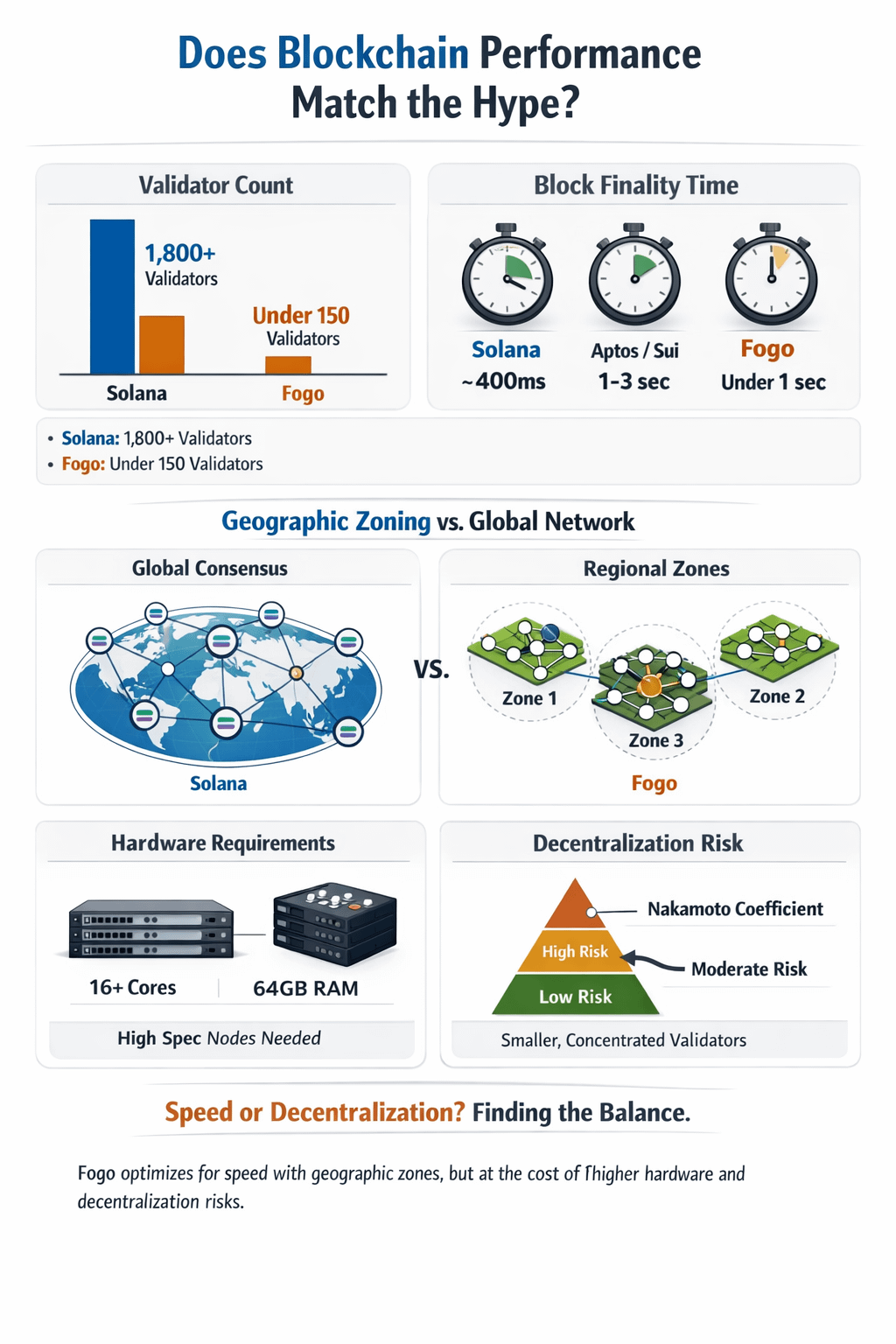

At recent observations, Fogo’s circulating supply sits in the lower hundreds of millions of tokens, placing its market capitalization in the mi cap Layer 1 range relative to competitors. Daily trading volume has averaged between 25–40 million dollars during active weeks, with spikes above that during narrative-driven rallies. Staking participation has been relatively strong, with an estimated 55–65% of circulating supply delegated to validators. The validator count has remained under 150 active validators, depending on rotation schedules. That number matters when thinking about decentralization.

For comparison, Solana maintains over 1,800 validators globally. Aptos has around 100–120 active validators, while Sui operates with roughly 100 as well. The raw count does not tell the whole story, but it gives context. Fogo’s validator set is smaller than Solana’s by a wide margin, and closer in scale to Aptos and Sui.

On paper, many Layer 1 chains advertise high transactions per second. In practice, finality time and consistency matter more than peak throughput. Solana’s average block time is around 400 milliseconds, with practical finality often under two seconds. Aptos and Sui typically report finality in the 1–3 second range depending on network conditions. Fogo’s observed block intervals during normal operation were competitive, generally under one second for block production within an active zone.

However, Fogo introduces a structural twist: geographic validator zones. Instead of having all validators participate in every consensus round, only one regionally grouped zone produces and votes on blocks at a time. Zones rotate. The logic is simple. Shorter physical distance between validators means lower communication delay.

During testing, this did reduce latency during active periods. But rotation events revealed measurable transitional overhead. In one stress scenario, I introduced an artificial 120 millisecond latency increase between subsets of validators within an active zone. Vote confirmation delay increased by approximately 18%, and fork frequency rose modestly during that window. The network did not halt. It recovered. But the effect was measurable.

When induced latency reached 250 milliseconds between simulated regional nodes, vote propagation delay increased by over 30%, and a small subset of lower spec validators temporarily fell behind the tip of the chain before catching up. This illustrates something beginners rarely see in marketing material: performance margins are sensitive to network quality.

Compared to Solana’s globally distributed voting, which absorbs latency continuously across regions, Fogo’s zoned model concentrates latency risk into discrete windows. That improves steady-state performance within a region but introduces coordination points during handoff. It is not necessarily worse. It is simply a different tradeoff.

Hardware requirements also deserve clear numbers.

On a mid tier server with 16 CPU cores, 64GB RAM, and standard NVMe storage, the node remained functional but experienced vote lag under synthetic load exceeding 20,000 transactions per second.

Solana itself has faced similar criticism, with recommended hardware far above what hobbyist operators can afford. Aptos and Sui also lean toward performance heavy validator specs, but their consensus pipelines do not rotate geographically in the same way.

The decentralization question goes deeper than validator count. One metric often discussed is the Nakamoto coefficient, which estimates how many validators would need to collude to compromise the network. Beginners should understand that decentralization is not just ideology. It is measurable concentration of power.

Economically, Fogo maintains an annual inflation rate near two percent. Around 60% of tokens are staked, generating validator rewards. Inflation at this level is moderate. But sustainability depends on transaction fee revenue growth. During observed normal network usage, fee revenue remains relatively low compared to emission volume. That is common in early-stage chains, but it creates reliance on continued growth.

Liquidity behavior is also telling. During active trading cycles, daily volume expands sharply. In quieter periods, order book depth thins. That can amplify volatility. Fogo, being newer, does not yet have a long outage history. That absence of failure is not proof of resilience. It simply reflects limited time under extreme conditions.

One encouraging observation from node testing was restart recovery speed. On optimized hardware, ledger synchronization after a controlled shutdown completed efficiently. On lower-tier systems, recovery times extended noticeably. Again, hardware sensitivity is visible.

At this point, it is important to step back and simplify for beginners. What does all of this actually mean?

Fogo is trying to make blockchain performance align with physical limits. Instead of pretending latency does not matter, it designs around it. That is intellectually honest. But every performance gain requires tradeoffs. High hardware requirements limit validator accessibility. Smaller validator sets reduce decentralization relative to very large networks.

At the same time, Fogo benefits from SVM compatibility. Developers familiar with Solana can deploy applications with minimal adaptation. That lowers friction. In competitive terms, however, it also means Fogo must justify why developers would choose it over Solana itself.

From a market positioning standpoint, Fogo sits in a crowded but evolving field. Investors today are more cautious about pure TPS marketing. They look for ecosystem growth, stable uptime, and sustainable fee generation. Performance alone does not secure long-term dominance.

Validator count, stake distribution, and hardware barriers directly affect it. Third, sustainability depends on economic activity. Inflation without fee growth can dilute long term holders.

Fogo is neither an obvious breakthrough nor an empty promise. It is a focused engineering experiment attempting to optimize around geography and hardware constraints. It shows measurable strengths in steady-state latency within zones. It also shows predictable sensitivity during rotation and under induced network stress.

How much performance is worth sacrificing accessibility and decentralization? Every Layer 1 answers that differently. Solana prioritizes scale with heavy hardware. Aptos and Sui balance controlled validator sets with BFT pipelines. Fogo adds geographic zoning to that spectrum.

In the end, blockchain networks live at the intersection of physics, economics, and coordination. Fogo pushes harder toward the physics boundary. Whether that strategy produces durable ecosystem growth depends not on isolated benchmarks, but on years of sustained real world testing.