I noticed something the other day that keeps looping in my head: you can tell, almost instantly, when someone is going to abandon a product. Not after a tutorial. Not after they “understand” it. In the first few seconds. Their thumb pauses, they squint a little, they hesitate—then they back out and you never see them again.

That moment is where most blockchains stop caring.

Vanar’s real-world adoption thesis begins exactly there, because it treats onboarding like a consumer event, not a crypto milestone. Not the “congrats, you made a wallet” moment. The real one: does the first experience feel natural enough that a normal person keeps going, or does it feel like work dressed up as innovation?

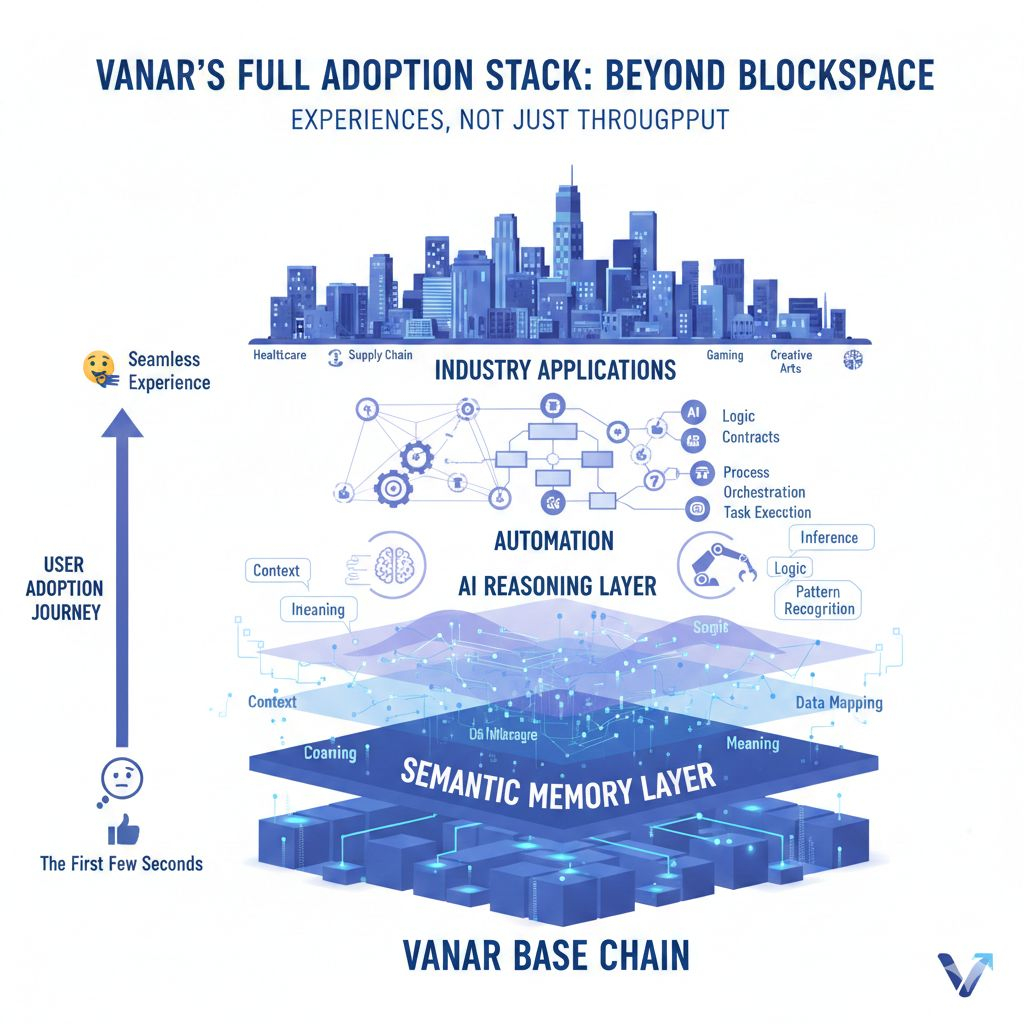

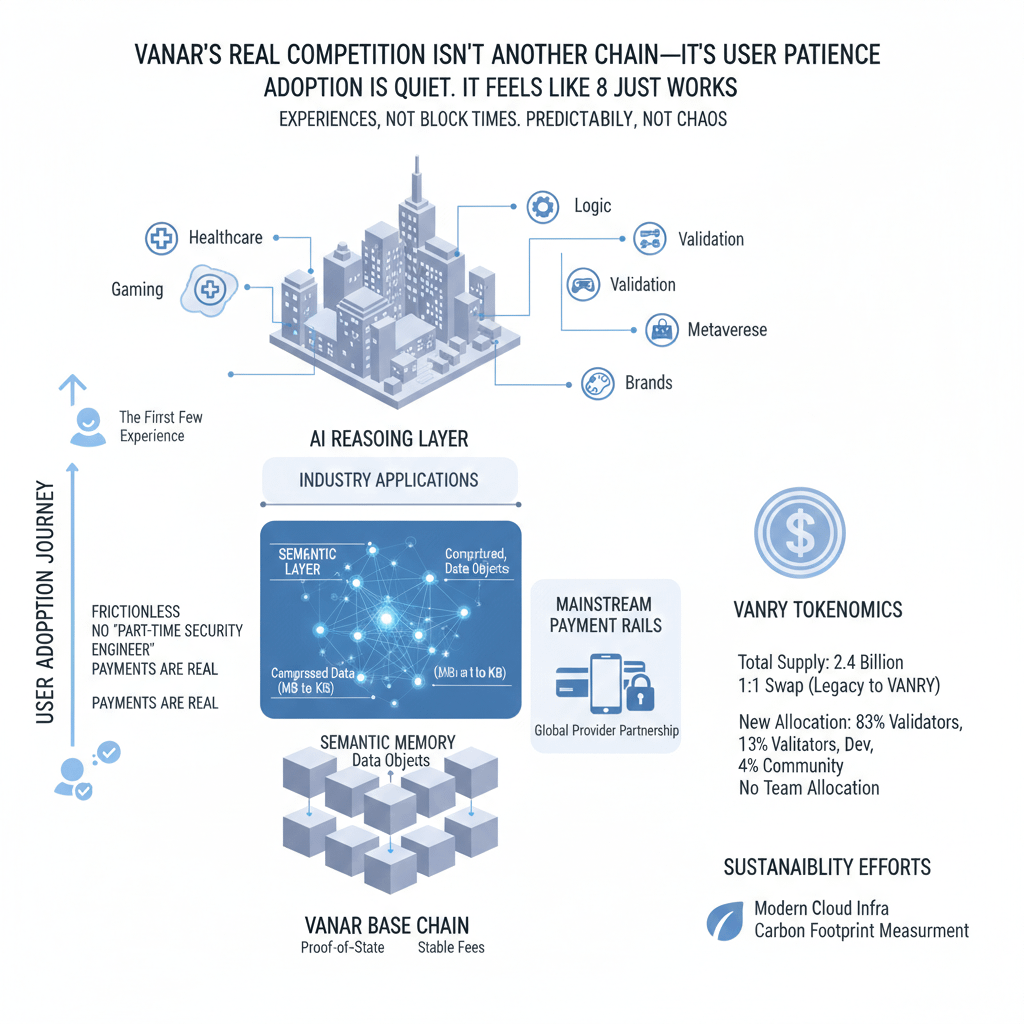

That’s why Vanar reads less like a singular technical layer and more like a full adoption stack. The chain is the base, sure—but the project keeps pointing beyond raw execution into a broader surface: memory, meaning, automation, and industry applications. Vanar frames this as a layered architecture: the base chain, then a semantic memory layer, then an AI reasoning layer, then automation, then industry-focused application flows. It’s a very different posture from the usual L1 pitch, where everything ends at blockspace and a marketing line about throughput.

And here’s the thing—people don’t adopt blockspace. They adopt experiences.

Organic adoption almost never happens because someone read about block times. It happens when a friend says, “Join this,” and the joining doesn’t hurt. When a player enters a gaming environment, creates a profile, claims an item, buys a skin, shows it off. When a brand experience is already being talked about, and participation feels like walking through an open door—no friction, no ceremony, no “now please become a part-time security engineer.”

Payments are the line where adoption stops being a story and becomes real. Demos are easy. Spending is honest. The second someone can move value, buy something, or settle a transaction without the system making them feel stupid, adoption shifts from theoretical to tangible.

That’s why I pay attention to the signals Vanar puts out around mainstream payment rails. The project has publicly positioned itself around real-world payment use cases and has announced a strategic partnership with a major global payment provider to explore Web3 payment products and infrastructure bridging. That kind of alignment matters, because it suggests Vanar isn’t only optimizing for crypto-native applause; it’s trying to meet the realities of consumer behavior and commerce where they actually live.

There’s also a quieter, underappreciated part of adoption: predictability. Consumers don’t care if fees are low on a good day. They care if the button works every day. Builders care too, because pricing chaos turns product design into guesswork. Vanar’s material repeatedly leans toward stable, usable network behavior—less “watch the mempool weather” and more “ship a product that behaves like a product.”

Even in the small builder-facing details, you can see the bias toward removing friction. The network details are publicly defined: a mainnet RPC endpoint, a chain ID of 2040, an official explorer, and clearly defined testnet information. That might sound basic, but it’s the kind of “boring clarity” that decides whether developers experiment today or put it off until never.

Where Vanar gets more ambitious—and honestly, more revealing—is in how it treats data and context as core primitives rather than offchain leftovers.

Its semantic memory layer is described as a system that takes raw data and turns it into structured, verifiable onchain objects designed to be queryable and executable. One of the headline claims is a compression approach—shrinking something like tens of megabytes of raw data into something closer to tens of kilobytes through semantic and algorithmic processing. Whether a developer uses that exact mechanism or not, the intent is clear: consumer apps generate messy, constant data—profiles, inventories, permissions, histories, receipts—and pushing all of it offchain turns “Web3” into a thin skin over a traditional backend. Vanar’s direction is basically: stop pretending the real app lives somewhere else.

Then its reasoning layer is positioned as the logic engine on top of that stored context—where rules, validation, and automated actions can happen with more awareness of what the data actually means. If your endgame includes real-world assets, brand workflows, and payments that don’t break when rules show up, reasoning and automation can’t be afterthoughts. They have to be native, or they’ll always be fragile add-ons.

All of this ties back to the consumer verticals Vanar keeps orbiting: gaming, entertainment, brands, metaverse experiences, AI-driven systems, and broader mainstream-facing solutions. The named ecosystem anchors that often come up—Virtua Metaverse and a games network layer—fit the thesis perfectly because they are not “features.” They are distribution. They’re the environments where people behave normally and adoption happens without anyone calling it adoption.

And then there’s the token layer—because even the best narrative collapses if the economic wiring is sloppy.

VANRY is the token powering the network’s activity model. The Ethereum contract reference you shared points to an ERC-20 deployment that shows a maximum total supply of 2,261,316,616 VANRY. In Vanar’s own tokenomics framing, the supply model is presented as 2.4 billion total, with 1.2 billion tied to the legacy supply via a 1:1 swap into VANRY, and an additional 1.2 billion allocated with a clear split: 83% toward validator rewards, 13% toward development rewards, and 4% toward airdrops and community incentives, with the document also stating no team token allocation. The 1:1 swap ratio has been repeated publicly as a core part of the rebrand and migration story.

Those numbers matter because they tell you what kind of network Vanar thinks it is. Reward-heavy allocations imply the long game is participation and network continuity, not a short-term attention cycle. Whether the execution matches the intention is always the real question—but the intention itself is readable.

Even sustainability messaging, which most people dismiss as fluffy, becomes practical if your target customer includes brands. Procurement teams and partnerships don’t treat sustainability like a vibe; they treat it like a checkbox with documentation. Vanar has publicly discussed eco-oriented efforts tied to modern cloud infrastructure and carbon footprint measurement ideas. Again, not a guarantee of anything by itself—but it signals Vanar is speaking a language that mainstream organizations already use: measurement, reporting, operational accountability.

If I zoom out and force myself to be honest about what’s different here, it’s not that Vanar claims it will onboard the next three billion. Everyone claims big numbers. The difference is that Vanar keeps returning to the parts most chains ignore: the first minute of user experience, the reality of payments, the friction builders face, the fact that data and context are not optional, and the truth that adoption rarely arrives as a deliberate “Web3 moment.” It arrives as normal behavior—play, profile, claim, buy, show, repeat.

And maybe that’s the cleanest way to say it: Vanar is trying to build a chain that makes sense to people who don’t care about chains.

Because if this thesis works, the win won’t look like crypto people finally agreeing that Vanar has good tech. It’ll look like someone joining a world their friends are already in, picking a name, claiming something that feels like theirs, buying a skin because it’s genuinely cool, and moving on with their day—without once thinking about block times, throughput, or what just signed behind the scenes.

That’s the ending I keep coming back to in my head: real adoption is quiet. It doesn’t announce itself. It just feels like the product finally stopped asking the user to do extra work—like the rails got out of the way—and life continued, smoothly, as if it was always supposed to be that simple.