02:11. The room is too clean to feel honest. One desk. One chair that squeaks if you lean back. The air-conditioning clicks like it’s keeping time. I’m alone with a dashboard that refuses to blink, as if stillness could be mistaken for certainty. Genesis supply in one column. Treasury ledger in another. Bridge escrow balances in a third. The numbers line up the way they always do—until they don’t. A small drift. Not a cliff, a hairline crack. The kind you could ignore if you wanted to sleep. The kind that becomes a screenshot if someone else finds it first. I zoom in, re-run the query, and the drift stays. My stomach does the thing it does when a system is technically fine but socially fragile. I open the runbook and feel, for a moment, the plain truth of it: trust doesn’t degrade politely—it snaps.

People like to say “real-world adoption” as if it’s a destination you arrive at in a press release. In practice it arrives as payroll dates, contract clauses, and somebody from a brand’s finance team asking for a plain explanation that doesn’t sound like a forum post. It arrives as a studio lead who doesn’t care about ideology, only whether settlement is stable enough to build on, because their players will punish them for any stutter. Vanar can be built with games, entertainment, and brands in mind. It can carry products across mainstream verticals—Virtua, VGN, whatever comes next. But the moment those words touch money that stands in for wages, obligations, and liabilities, the slogans stop being harmless. You find out what your design actually is when someone needs receipts, not vibes.

Genesis supply is the first receipt. It’s not a poetic “beginning.” It’s the initial state that every validator will replay, the line in the sand that determines whether your later explanations sound like evidence or like improvisation. If the genesis supply is vague, everything becomes an argument. If it is crisp, the arguments get smaller. That sounds abstract until you’re the one in a compliance call, hearing the pause after you say “approximately,” and realizing the pause is not confusion. It’s evaluation. The adult world does not hate uncertainty. It hates unbounded uncertainty. It will tolerate one missing decimal if you can show the system that prevents missing dollars.

The drift on my screen is tiny, but it has a story behind it. Somewhere in the path between wrappers and the native asset, between an ERC-20 representation and a BEP-20 representation and the chain’s own accounting, there are points where humans touch the system. Bridges. Migrations. Manual approvals. A key held by someone who also has a family and sleeps badly during launches. Everyone says bridges are risky, and then they treat the next bridge event like a routine batch job because routine is how you keep your heart rate down. Until it isn’t. Until you are awake at 02:11 and you realize there is no such thing as a small accounting error if it becomes a public question. It doesn’t matter if it’s a delayed update, a missed event log, a stale indexer. Once it exists, it can be weaponized. Once it exists, you have to answer like an adult.

This is where people confuse “public” with “provable.” They are not the same. Public is visibility. Provable is correctness. A system can be totally public and still leave you guessing what matters. Who authorized that move? Was it inside policy? Did it violate a lock? Was it a treasury release or a compromised key? Public data does not automatically become meaningful evidence. And the opposite is also true: a system can keep details private and still be provably correct about the rules that matter—totals, conservation, authorization, and compliance with issuance schedules. Privacy isn’t just a preference when money touches employment or legal agreements. Sometimes privacy is a duty. It is not optional to expose salaries to the entire internet. It is not clever to publish vendor pricing as a permanent ledger artifact. But auditability is non-negotiable. If you can’t prove you followed your own rules, privacy turns into an excuse, and excuses don’t survive audits.

So the problem is not “should everything be visible.” The problem is “what must be provable, and to whom, and under what procedure.” What we actually need is confidentiality with enforcement. Validity proofs without leaking unnecessary details. Selective disclosure to authorized parties—auditors, regulators, compliance teams, internal risk. Not secrecy. Controlled truth. The best metaphor I’ve heard in a real audit wasn’t technical. It was human. A sealed folder in an audit room. The folder is complete, consistent, and rules-based. It contains what’s necessary to establish that the system behaved correctly. It isn’t dumped on the street. It’s opened when there’s standing. There’s an access log. There are names. If access needs to be revoked, it’s revoked and recorded. The folder is not a vibe. It’s procedure.

That is why Phoenix private transactions make sense when you stop talking about them like a magic trick and start talking about them like audit-room logic on a ledger. Verify correctness without permanent public gossip. The ledger can prove a transaction is valid—balances conserved, constraints respected, issuance schedule obeyed—without turning every business move into a permanent rumor. In the real world, indiscriminate transparency can be harm. It can reveal client positioning. It can expose salaries. It can damage vendor relations. It can leak trading intent. It can create avoidable market impact. Sometimes transparency doesn’t increase trust; it increases predation. You don’t build for the best-case audience. You build for the one that will use your data as leverage.

The practical design question becomes almost painfully simple: can the ledger know when to speak and when to shut up, while remaining accountable? You can feel the weight of that question when you’re building for brands, for games, for people who have legal departments and reputations and internal controls. They don’t want drama. They want boring. They want “dependable” the way a bank transfer is dependable, even if the bank itself is slow and bureaucratic. They want the settlement layer to be conservative, almost dull, because dull is what holds up under scrutiny. They want innovation contained, not smeared across the foundation.

That’s where Vanar’s architecture matters, not as a design flourish but as containment. Modular execution environments over a conservative settlement layer. You let different verticals move at different speeds without asking the base layer to become a circus. Settlement should be boring because settlement is where you point when someone says, “Prove it.” Separation is not aesthetics. Separation is how you prevent one ambitious feature from dragging the entire chain into instability. It’s how you keep the core dependable while still letting new environments exist for gaming, metaverse, AI, and brand solutions, each with their own operational needs and failure modes.

EVM compatibility fits into this the same way familiar tools fit into an emergency kit. Not glamorous. Practical. Reduced operational friction. Fewer ways to fail. When something breaks at 02:11, you don’t want to be diagnosing a brand-new set of behaviors with no shared language. You want patterns your auditors recognize. Tooling your security team has seen. Incident responders who can say, “I’ve seen this failure mode before,” and mean it. Every new execution model is a new catalog of mistakes. If you can lower the novelty, you lower the risk. And in an operations-first world, lowering risk is a feature.

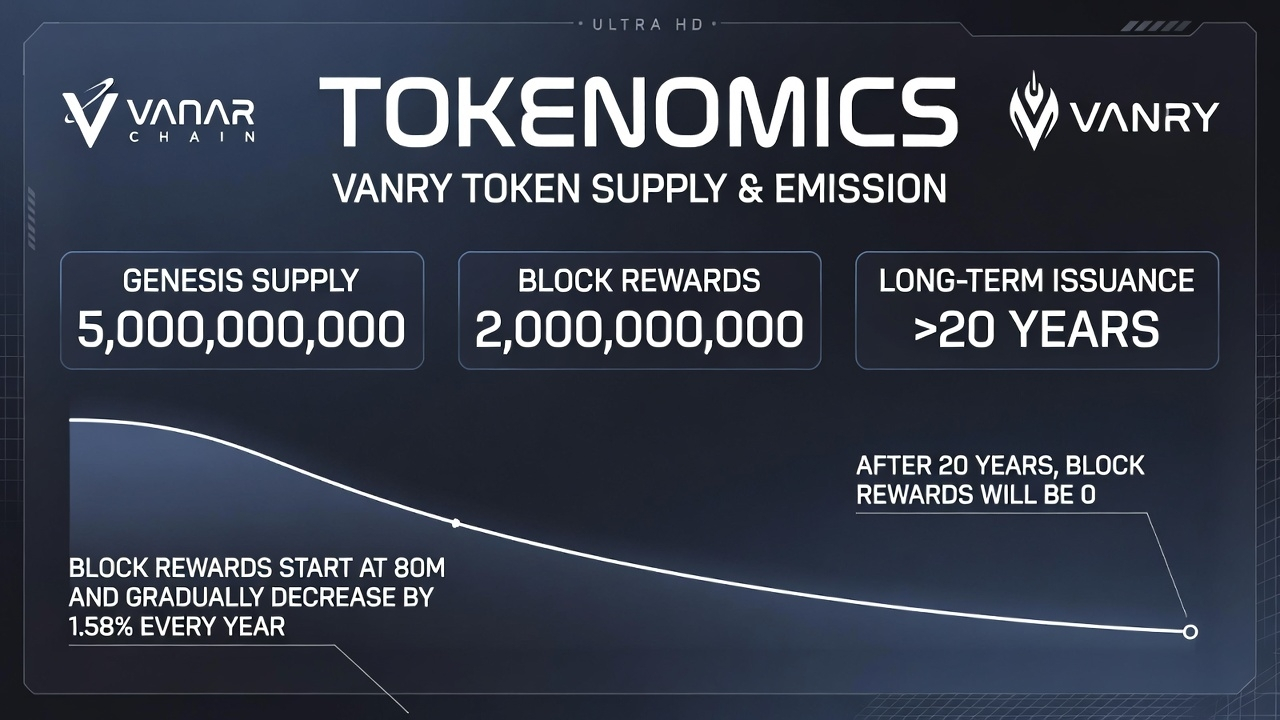

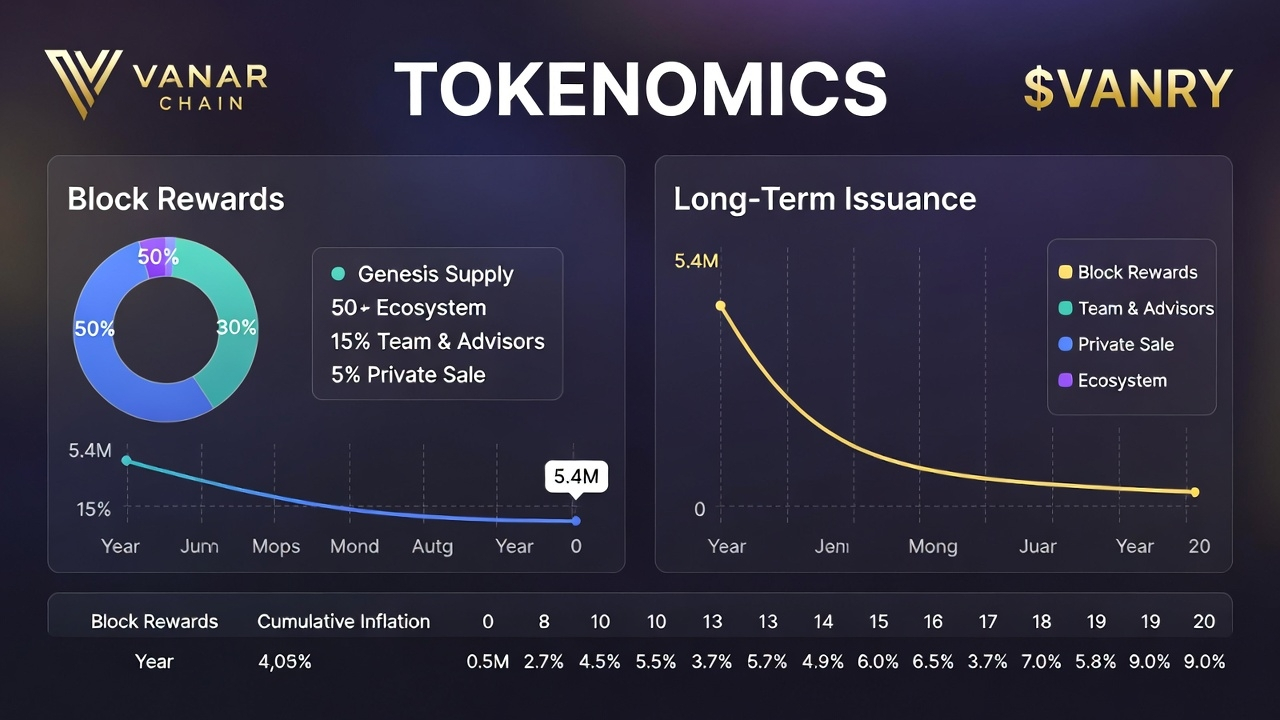

Tokenomics gets romanticized as narrative. In the room, it is closer to scheduling and enforcement. Genesis supply is the initial commitment. Block rewards are the recurring obligation, the predictable rhythm that keeps validators paid and security funded without improvisation. The reward logic has to be boring in the way payroll is boring. No surprises. No “we’ll fix it later.” The chain must do what it said it would do, every block, even when nobody is watching—especially when nobody is watching. That’s the unglamorous meaning of “trustless.” Not that humans don’t matter, but that the system doesn’t require a human mood to remain honest.

Long-term issuance is where patience becomes policy. Legitimacy takes time. Regulation takes time. Adoption takes time. You can’t compress those timelines just because you want to. Emissions across a long horizon can be a recognition that the chain expects to be here long enough to endure audits, incidents, leadership changes, shifting laws, and changing market structure. It is not a promise of abundance. It is a discipline of continuity. It forces the organization to live with its decisions for years, not quarters. It forces you to build controls that outlast the people who wrote them.

In that context, $VANRY isn’t a price chart. It’s a responsibility object. A mechanism that binds security to consequence. Staking is not a fan club. It’s a bond. It is a way of saying: if you help secure this ledger, you put something real at risk, and if you fail—through malice, negligence, or exhaustion—the system has teeth. Skin in the game isn’t motivational language when you are writing the policy that defines what gets penalized and how disputes are handled. Enforcement must be consistent. Documented. Reviewable. Otherwise it becomes discretionary. Discretion becomes politics. Politics becomes drift. And drift is how systems die without noticing until the damage is public.

The drift on my dashboard is still there. I pull up the bridge logs and see a delayed event indexing job. Not malicious, just brittle. A timeout that didn’t page anyone because the alert threshold was tuned for last month’s traffic. A single missed heartbeat that turned reconciliation into a guess. This is what operational chokepoints look like: not explosions, but quiet failures that accumulate until they become questions. The fix is boring. A better retry policy. A tighter reconciliation loop between settlement and treasury accounting. Alerts that assume things will go wrong at the worst possible time. A checklist that gets followed even when people are tired, because tired people are exactly who the checklist is for.

There is a kind of honesty that only shows up when you stop pretending the system runs itself. Key management isn’t a footnote. It’s a daily risk. People store secrets in the wrong place. They share screens on calls. They copy-paste into the wrong chat. They confuse test wallets with production wallets at the end of a long day. They approve something too quickly because the meeting is running over and everyone wants to go home. The chain can be designed well and still be undermined by human error. That’s why credibility lives in boring controls: permissions, disclosure rules, revocation, recovery, accountability. The language of compliance—MiCAR-style obligations, custody responsibilities, audit trails—doesn’t care how elegant your consensus is. It cares whether you can demonstrate control without improvisation.

By 04:03, the discrepancy resolves. The indexer catches up. The minted amount and the released amount converge the way they should have from the start. The chain didn’t lie. The organization almost did, by omission, simply by not noticing quickly enough. I write the incident note in the same tone I’d want someone to use if the roles were reversed. What happened. Why it happened. What we changed. What we will monitor now. I avoid grand conclusions because grand conclusions are how you avoid the small, tedious work that prevents repeats. The best incident reports don’t sound heroic. They sound tired and exact.

Tokenomics, seen from inside, is just a set of promises that have to survive contact with reality. Genesis supply is the first promise, frozen into the system. Block rewards are the ongoing promise, repeated until repetition becomes credibility. Long-term issuance is the patience to accept that legitimacy is earned slowly, under scrutiny, and that adoption is less about slogans than about the absence of surprises. Phoenix private transactions are not about hiding; they are about proving correctness without turning every sensitive detail into permanent public gossip, and about giving lawful, rules-based disclosure the same seriousness as cryptographic validity.

In the end, the work returns to two rooms that matter. The audit room, where the sealed folder gets opened under procedure and the ledger is asked to prove it did what it claimed. And the other room, quiet in a different way, where someone signs their name under risk—real money, real obligations, real consequences. The ledger has to know when to speak and when to shut up. It has to remain accountable either way. And the people running it have to remember that trust doesn’t fail gradually. It fails in one clean, irreversible moment, usually after a small discrepancy that someone ignored at 02:11.