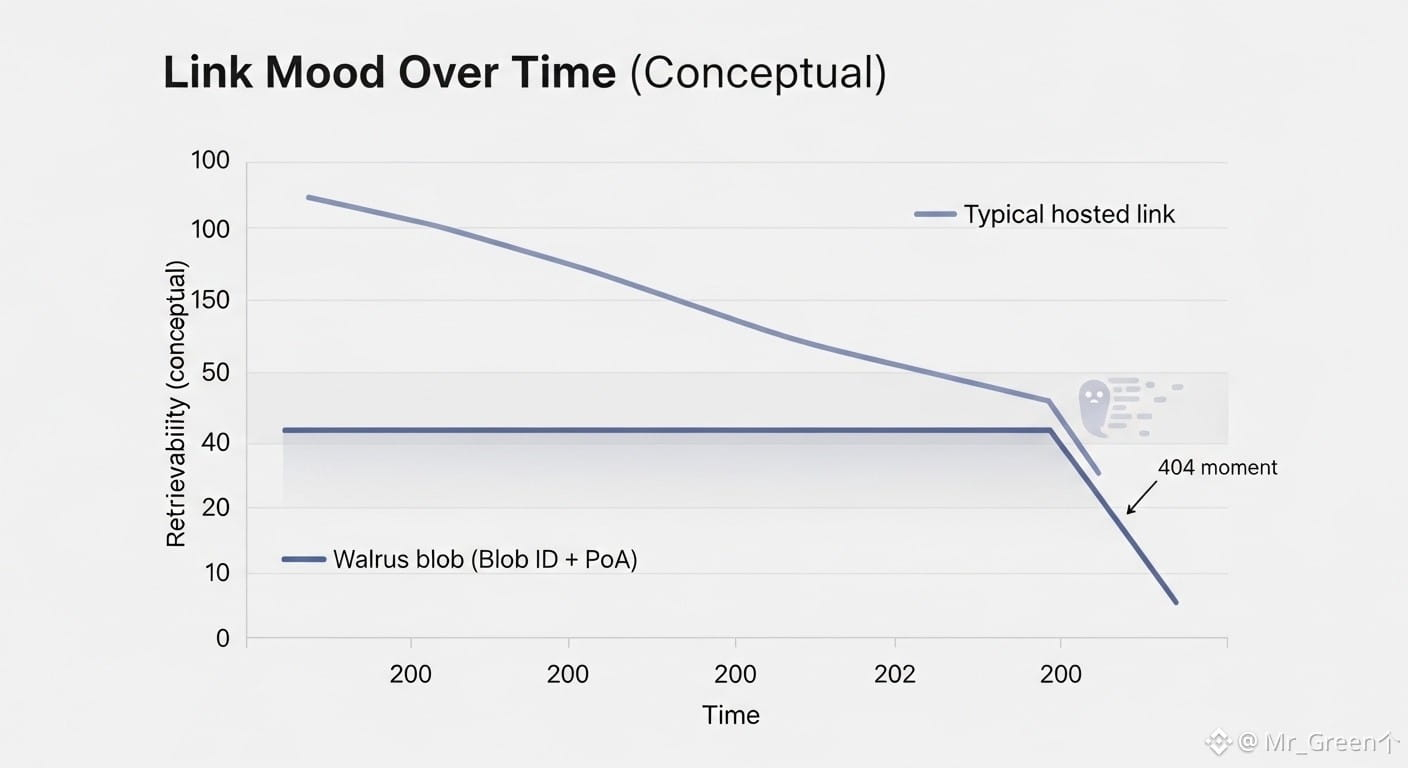

I used to think storage was simple. You upload a file, you download a file, life goes on. Then Web3 taught me a strange lesson: a system can be decentralized in every proud, ideological way… and still depend on a link that behaves like a flaky friend. It’s always fine until the day you need it. Then suddenly the file is “temporarily unavailable,” the host is “under maintenance,” and your confidence evaporates like a tweet after a bad take.

Walrus shows up in this story like the one calm person at a chaotic group project. It doesn’t try to make storage feel magical. It tries to make storage feel accountable.

Walrus is a decentralized storage protocol designed for large, unstructured content called blobs. A blob is simply a file or data object that is not stored as rows in a database table. Walrus supports storing and reading blobs, and it supports proving and verifying that a blob has been stored and is available for retrieval later. It is designed to keep content retrievable even if some storage nodes fail or behave maliciously, what engineers often call Byzantine faults. Walrus integrates with the Sui blockchain for coordination, payments, and availability attestations, while keeping blob contents off-chain. Only metadata is exposed to Sui or its validators.

Now, here’s the new concept: think of Walrus as a notary public for large data—not in the legal sense, but in the “everyone can check the paperwork” sense.

Most storage feels like a promise. “Trust me, it’s stored.” That works until it doesn’t. Walrus tries to replace that vague promise with a clear, checkable chain of facts. It wants your data to behave less like an informal agreement and more like something you could bring into a dispute and say, “Here. This is the record.”

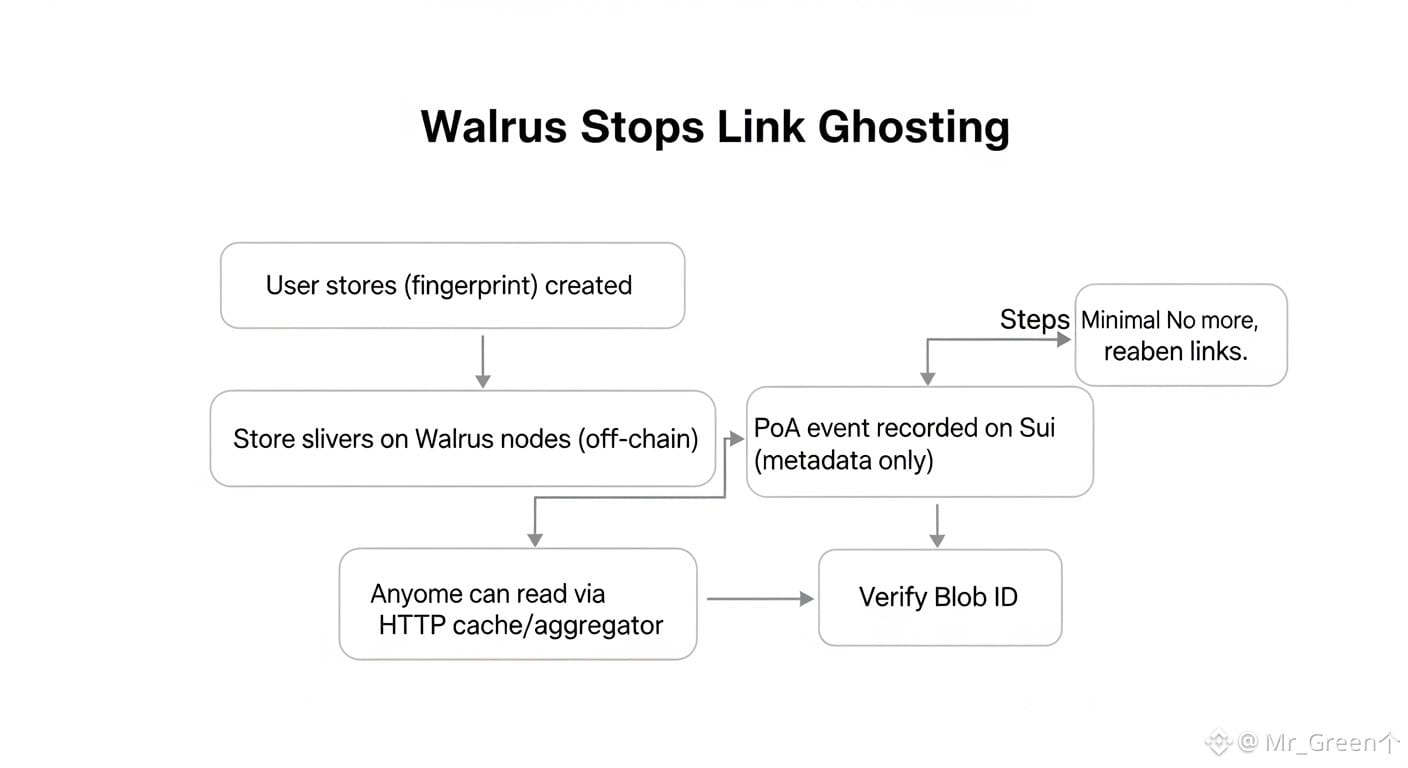

The first piece of that record is the blob ID. Walrus gives each blob an identity that is derived from its encoding and metadata. In plain language, it’s a fingerprint. The point of a fingerprint is not that it is fancy; the point is that it is specific. If you retrieve the blob later, directly from storage nodes or through caches or aggregators that serve content over normal HTTP, you can verify that what you got matches the blob ID you expected. It’s a way to reduce a very common kind of pain: “I downloaded something, but is it the same thing?”

Then Walrus adds a second piece: time-bound responsibility. It defines a Point of Availability, or PoA. PoA is the moment Walrus takes responsibility for keeping the blob available. It also defines an availability period, how long that responsibility lasts. Both PoA and the availability period are observable through events on Sui. This is a big difference from the “upload and hope” model. In Walrus, storage is not only a location. It is a lifecycle with a public marker that says when the network became accountable.

If you’re building in Web3, that accountability travels surprisingly far.

A DeFi team might need to publish large proof bundles, audit packs, or historical archives that are too bulky to store on-chain. With Walrus, those artifacts can live as blobs, with an on-chain record that they were available for a defined time window. A governance community might want proposals and research to remain retrievable long after the vote. An NFT project might want media to stop living on fragile hosting that breaks quietly. An AI team might want datasets or model artifacts to have verifiable identities and provable availability so provenance isn’t just a story.

Walrus isn’t saying, “Everything belongs on-chain.” It’s saying, “If the data is off-chain, it should still be verifiable.”

Under the hood, Walrus tries to keep this verifiability practical at scale. It uses erasure coding to split each blob into pieces and distribute them across storage shards. This improves robustness without full replication. Walrus describes overhead expansion of about 4.5–5×, which is far lower than storing large data directly as on-chain objects with full replication. It also describes being able to reconstruct a blob from about one-third of the encoded symbols, which helps reads succeed even when some nodes are down or unhelpful. The system is designed with Byzantine conditions in mind, and it assumes that within each storage epoch, more than two-thirds of shards are managed by correct storage nodes, tolerating up to one-third faulty or malicious.

This is where the “notary” idea gets stronger. A notary doesn’t prevent chaos in the world. A notary creates a record that still makes sense even when the world is chaotic. Walrus is built on the idea that networks will be messy, nodes disappear, connections fail, some participants behave badly, so the protocol should remain coherent anyway.

It also helps that Walrus is explicit about what it is not. It does not try to rebuild a global CDN. It is designed to work with caches and CDNs rather than replace them. It does not try to become a full smart contract platform; it relies on Sui smart contracts for coordination and governance operations. It supports encrypted blobs, but it is not a key management system. These boundaries matter because they prevent the protocol from collapsing under the weight of too many responsibilities.

There is also an economic layer that keeps the promise alive over time. Walrus uses a native token, WAL, for storage payments and for delegated stake that helps determine the storage node committee across epochs. Rewards are distributed to storage nodes and their stakers based on protocol processes at the end of each epoch. The point isn’t to make the token feel exciting. The point is to make storage feel sustainable: operators need incentives to keep serving and maintaining availability, especially after the novelty fades and real users depend on the system.

If you zoom out, Walrus is trying to give Web3 a missing middle layer. We already have chains that execute and record state. We already have apps that present interfaces. But the large data those apps reference often sits in a fragile limbo. Walrus tries to make that limbo more structured: large blobs off-chain, but with on-chain receipts and verifiable identity.

And that’s the funny part. In most of crypto, people chase “trustless” like it’s an emotion. Walrus chases something simpler: auditability. The feeling you get when you can stop arguing and start checking.

So yes, you could say Walrus is “decentralized storage.” But the more precise description is this: Walrus is a system that wants your data to stop acting mysterious. It wants your files to stop ghosting you. It wants them to show up with a name tag, a receipt, and a time window that everyone can verify.

In a space where confidence often comes from vibes, Walrus is trying to build confidence from evidence. That’s not a punchline. But it is, honestly, a relief.