I keep thinking about a small, ordinary moment that happens more often than people admit, the kind of moment that doesn’t look like “failure” from the outside but quietly decides whether a technology ever becomes mainstream: someone opens a crypto app to do a simple thing—send money to a friend, pay for something small, move value across a border—and the interface immediately starts demanding attention for problems the user never agreed to solve, problems about networks and approvals and gas and retries, until the task stops feeling like a normal action and starts feeling like a ritual you either learn or avoid.

That’s the emotional backdrop for the Vanar thesis, because Vanar’s materials are interesting less for the vocabulary and more for the direction they point toward, where the chain is not framed as a place that merely records raw events but as a place where information is compressed, structured, and made usable by machines, which is exactly the kind of shift you would expect if the end goal is not “apps tolerated by power users” but “apps that feel normal to billions,” the kind of normal where people stop thinking about the infrastructure the way nobody thinks about the protocols underneath a video call while they’re simply trying to talk.

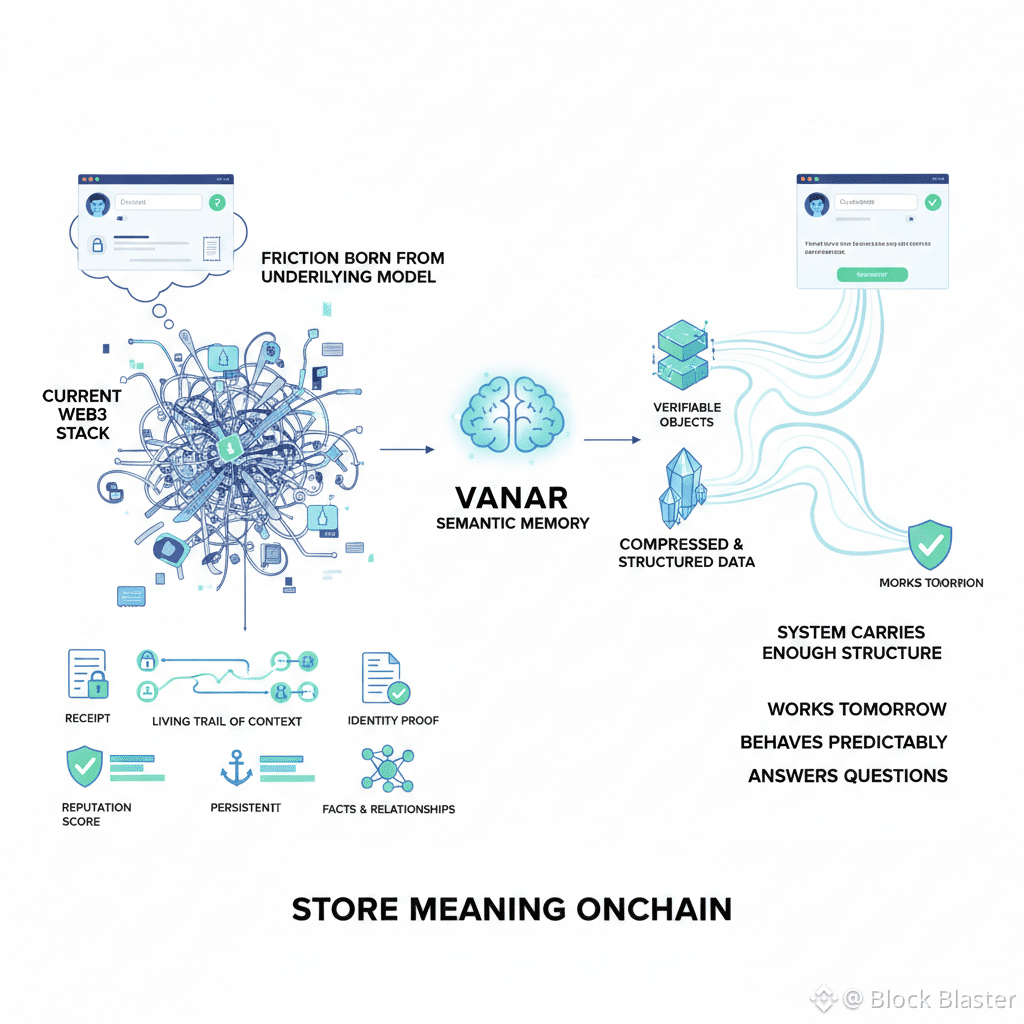

Most blockchains, even the technically impressive ones, still behave like extremely reliable receipt printers: they execute state changes, emit logs, and leave meaning—context, interpretation, relationships between facts—to be reconstructed later by indexers, dashboards, and whatever offchain services a team can keep alive, which works when your audience is crypto-native and unusually patient, but becomes fragile the moment you try to build consumer experiences that need to feel consistent under load, consistent across regions, and consistent for people who will never accept “learn the rituals first” as a reasonable product requirement.

Vanar’s bet is that you don’t reach scale by polishing the same interface over the same underlying model, because the underlying model is exactly where the friction is born, and the only durable way to reduce friction is to change what the system can natively represent, since “meaning” in software is not a philosophical layer, it is the practical difference between a system that knows an action happened and a system that knows what that action implies, what it authorizes, what it proves, what it should trigger next, and how it can be verified later without a human standing in the middle translating everything into something operational.

This is where Vanar’s semantic memory idea becomes the real centerpiece, because it is presented not as “storage” in the usual sense but as an attempt to compress and structure data into objects that can be verified and used by machines, a move that speaks directly to the real world where most useful digital activity is not a single transfer but a living trail of context: receipts that need to survive, permissions that need to remain legible, identity proofs that need to be reusable, media that should not quietly disappear, reputations that need continuity, and relationships between facts that cannot be safely reconstructed later by whichever API happens to be running this month.

When you look at adoption through that lens, “store meaning onchain” stops sounding like a slogan and starts sounding like a response to a real weakness in the current web3 stack, because the average user does not consciously care whether something is onchain or offchain, they care whether it still works tomorrow, whether it behaves predictably when they repeat the same action, and whether the app can answer questions without pushing them into a maze of explorers and dashboards, and a semantic memory approach is basically a bet that the system itself should carry enough structure that retrieval and verification stop being a fragile afterthought.

From there, the reasoning layer becomes the natural next step in the story, because memory without interpretation is still just an archive, and interpretation is the difference between software that can show you what happened and software that can make decisions under constraints, the kind of decisions that in real life always sit under eligibility rules, risk rules, compliance rules, and accountability, which is exactly why “agents” remain toys in most ecosystems: they can talk, but they cannot reliably justify what they are doing, and the moment a system cannot justify itself is the moment a serious business refuses to rely on it.

If you take Vanar’s stack direction seriously, the next move after semantic memory and reasoning is automation, because the whole point of agents is not conversation, it is execution, and execution is where systems either become useful or become dangerous, since automation without auditability becomes an invisible risk machine while automation without practical permissioning becomes ceremonial and slow, so the only version that survives outside crypto-native circles is the one that can act while leaving a trail clear enough that a serious organization can defend the action later without hand-waving.

And then you arrive at the part that quietly decides whether the vision ever reaches mainstream users: flows, the idea that you package the stack into repeatable, industry-shaped workflows so teams do not have to invent their own worldview from scratch, because scale is rarely about architecture diagrams and almost always about templates that work, templates that teams can adopt without hiring a research department, templates that let them ship experiences users already understand, which is how infrastructure wins in the real world—by being hidden inside something familiar, so nobody has to learn a new language just to do an old task.

This is also why Vanar’s emphasis on games, entertainment, and brands matters in a way that is easy to underestimate, because those verticals do not politely tolerate friction in the name of ideology, they punish it immediately and at scale, and anyone who has watched a mainstream user bounce off a wallet prompt knows that “good enough” in crypto is not even close to good enough in consumer products, so when a chain frames itself around bringing the next billions through those industries, it is effectively choosing the harshest possible UX judge and declaring that invisibility, predictability, and normalcy are the standards, not optional extras.

Somewhere underneath all of this sits the token layer—VANRY—doing what token layers do, anchoring the economics of activity and security while remaining, ideally, invisible to the end user, because at true consumer scale the token cannot be the star of the experience without turning every interaction into a financial decision, and the only way billions arrive is when the system stops asking people to think like traders and starts letting them behave like humans who simply want the app to work, the way every successful consumer platform works.

So the part that stays with me is not the claim that Vanar is “another L1,” and not even the claim that it is “AI-native,” but the quieter argument hidden inside the structure of its stack: that raw events are not enough, that meaning has to be stored in a form machines can use, that reasoning has to be native enough to be reliable, and that automation has to be safe enough to be boring, because only boring systems become infrastructure, and only infrastructure touches billions without needing to be constantly explained.

And maybe that’s the most honest way to end it, because I’m not chasing a future where everyone becomes a crypto expert or where every person learns to care about networks and gas and signatures, I’m chasing a future where none of that needs to be taught in the first place, where the technology stops demanding attention and starts earning trust quietly, the way good systems always do, by feeling so natural that people forget there was ever a time when moving value or proving something online felt like homework.