The government shutdown has created a historic statistical void; this puzzle-like CPI report, with each piece potentially leading the Federal Reserve and the market to different conclusions.

At 21:30 on December 19 (Thursday) in the UTC+8 time zone, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) will release the November Consumer Price Index (CPI) report.

Due to the government shutdown, this is the first inflation data release since September. The report is complicated not only by the missing October data but also faces questions about its quality due to incomplete data collection.

1. Market Expectations and Core Concerns

1. Market Expectations and Core Concerns

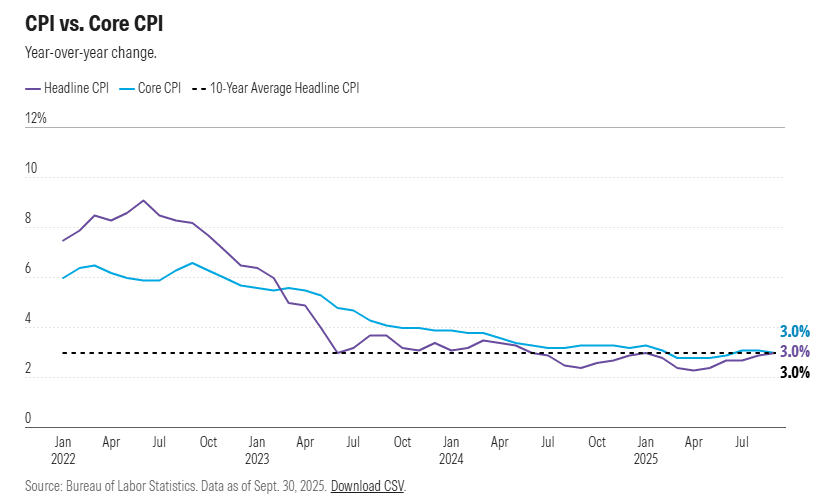

● According to consensus forecasts from financial data company FactSet, economists generally expect the November CPI to rise by 3.1% compared to the same period last year, slightly higher than September's 3.0%. The core CPI, which excludes food and energy price fluctuations, is also expected to see a year-on-year increase of 3.1%.

● From a month-on-month (monthly rate) perspective, since officials will be unable to provide data comparing changes from the previous month, economists estimate based on September levels, expecting an overall CPI month-on-month increase of 0.25% and a core CPI month-on-month increase of 0.3%.

● Christopher Hodge, Chief U.S. Economist at Crédit Agricole, bluntly stated that the market is more concerned about month-on-month changes, as they better reveal short-term inflation trends, while year-on-year data has limited signaling.

Two, the dual-month data and quality doubts

Two, the dual-month data and quality doubts

● The absence of October data is a core challenge. Due to the federal government shutdown interrupting the collection of price data, the BLS canceled the October CPI release. An official spokesperson stated that the November press release and database will not contain month-over-month percentage change data.

● Therefore, the November CPI report essentially reflects the cumulative price changes from September to November. The Richmond Fed pointed out in an analysis that this is an unprecedented situation in history, marking the first interruption of monthly CPI data series since January 1921.

● Data quality issues are also prominent. Goldman Sachs economists point out that due to the shutdown lasting until November 13, coupled with the Thanksgiving holiday, the time available for collecting price data that month was significantly shortened, and the number of samples collected may be fewer than usual.

● Since many commodity prices typically decline at the start of the mid-November holiday sales season, price collection concentrated in the latter half of the month may produce a downward bias in the data.

Three, the main forces driving inflation

● Tariffs are widely regarded as a key factor driving up commodity inflation. An analysis from the Economic and Policy Research Center predicts that since September, prices for goods such as automobiles, home appliances, and clothing have continued to rise under the impact of tariffs.

● Housing costs may exhibit a differentiated trend. The inflation rates for primary residential rents and owners' equivalent rents showed signs of slowing in September. Although rents may rebound in November, Interactive Brokers economist José Torres believes that high mortgage rates and tight immigration policies will continue to limit a strong rebound in housing costs.

● Additionally, food inflation may remain high. Wholesale food prices in September (especially beef and turkey) saw significant jumps.

● In terms of energy and insurance, due to seasonal adjustments, gasoline prices may show an increase in the report, while auto insurance prices are expected to record a substantial increase once again.

Four, the Federal Reserve's dilemma and market outlook

Four, the Federal Reserve's dilemma and market outlook

● The inflation outlook is crucial for the Federal Reserve's monetary policy. The current market forecast for an inflation rate of 3.1% is still more than a percentage point higher than the Federal Reserve's long-term target of 2%.

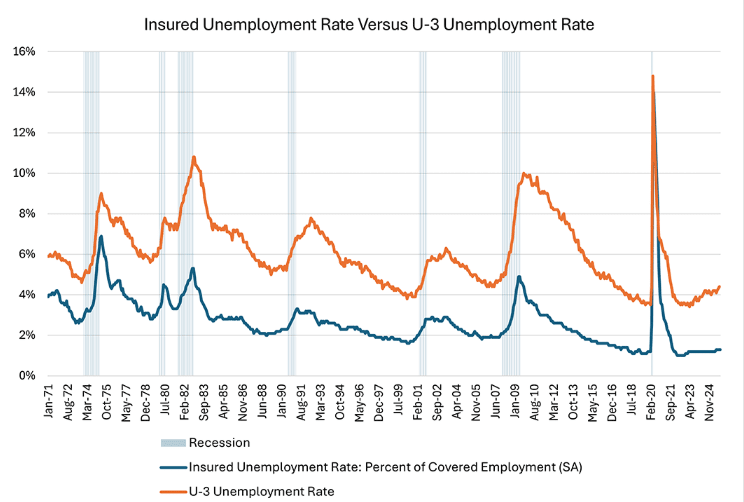

● The latest survey from the New York Fed shows that the median inflation expectation for American households for the next year remains at 3.2%, while expectations for the next three and five years stabilize at 3%.

● Some economists believe that if tariff levels do not increase further, their impetus for inflation should be viewed as a one-time effect, and inflation may again tend to ease in the future. For example, Torres predicts that by the summer of 2026, inflation may stabilize around 2.5%.

Five, how to interpret this 'non-standard' report?

Given the report's uniqueness, several institutions recommend that investors remain cautious.

● UBS economists believe that the market should 'hardly pay attention' to the upcoming November CPI data, as its information base is weaker than in regular months and relies on technological assumptions that are not fully disclosed.

They believe that the data bias caused by the government shutdown may only be completely eliminated when the April CPI report is released in May 2026.

● Therefore, a more reasonable approach is to combine the inflation data for November and December as a reference for assessing inflation trends in the fourth quarter. At the same time, closer attention should be paid to the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, which is more valued by the Federal Reserve, as it is not affected by changes in the way health insurance is calculated in the CPI.

The historical statistical series was unexpectedly interrupted by the government shutdown, and tonight's data will be a 'two-month puzzle'. Although analysts attempted to depict a 'ghost image' of October inflation from high-frequency data and model extrapolations, the true outline has already become blurred.

Signals beyond the data are more worthy of attention: under the triple pressure of price stickiness, tariff pressures, and stubborn household inflation expectations, the Federal Reserve's path to a 2% target interest rate seems to be longer than a rugged mountain road lacking signposts.