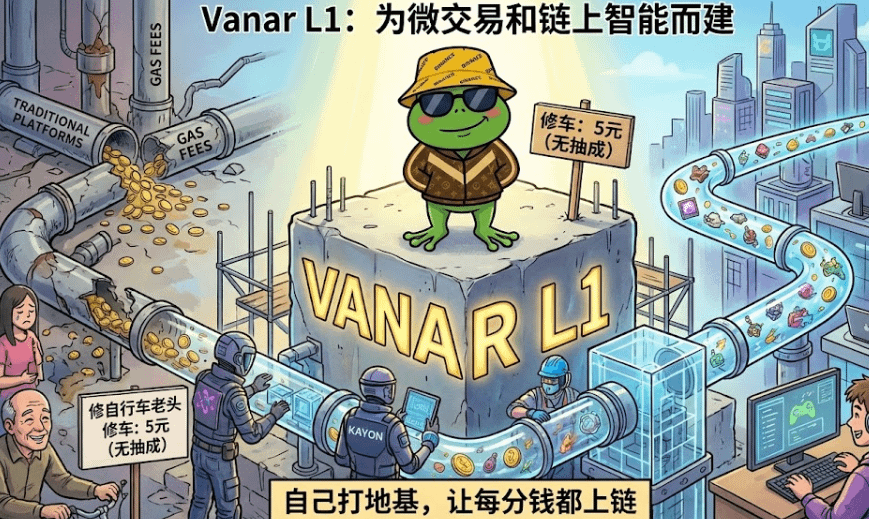

There is an old man repairing bicycles at the entrance of my neighborhood downstairs, and he has been doing it for more than twenty years. A few days ago, I went to fix a flat tire, 5 yuan. He pulled out his phone for me to scan, and after I finished scanning, he sighed: “It’s 4.6 yuan, and I’m taking away 0.4 yuan.”

0.4 yuan. I didn’t say anything. But I was thinking, this old man repairs twenty tires a day, and in a month, he has lost more than 200 yuan to this invisible pipeline. He doesn’t know where this money goes, nor has anyone explained to him the concept of 'payment channel fees.' He just vaguely feels that digitization has cost him something.

This incident made me understand that @Vanarchain is right here.

Microtransactions in the gaming industry are much worse than repairing bicycles. A player spends 6 yuan on a skin, the platform takes a 30% cut, the payment channel takes a bit more, and the developer might end up with just over 3 yuan. This is still in a centralized world. When you move the bots onto the chain, Ethereum's mainnet gas fees can easily reach dozens of dollars, making a 6 yuan transaction impossible to run.

L2 is a solution, but it hasn't addressed the fundamental problem. Rollups compress transactions, which indeed makes them cheaper, but for microtransactions worth a few cents, it still presents challenges. Not to mention the user experience of L2—cross-chain bridging, asset migration, waiting for confirmations—each step can be discouraging.

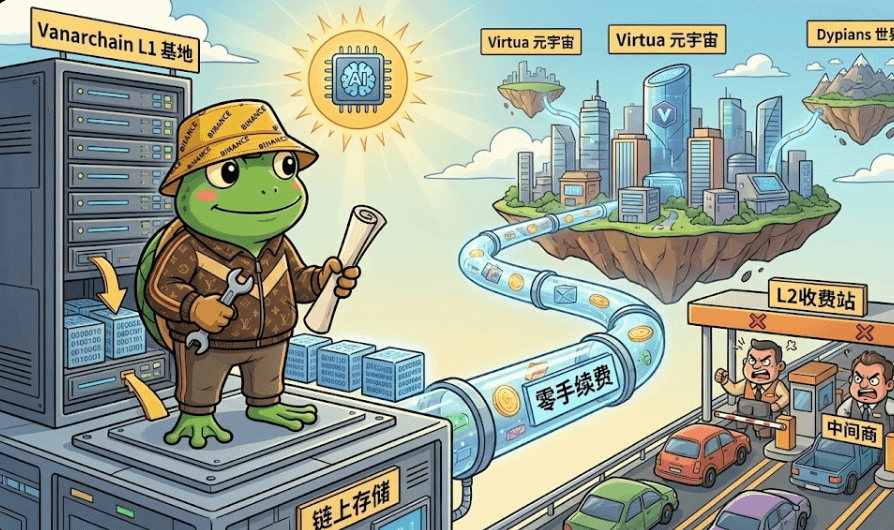

#vanar chose a more cumbersome path: to create an L1 themselves.

What's the issue? L1 means you have to re-establish your mindset, re-accumulate nodes, and re-encourage developers and users to migrate over. This isn't an easy task. But Vanar's logic is: if you want to reduce transaction fees to truly zero or close to it, if you want to enable transactions of a few cents for items in games to go on-chain, you cannot build on someone else's foundation. You have to lay your own foundation.

They have done a few things on this chain that I think are noteworthy.

The first thing is on-chain backup storage. Currently, most NFT metadata hangs on IPFS, images exist on AWS or Arweave, and only a pointer is stored on-chain. This means your NFT itself is 'empty'; its content relies on the stability of off-chain services. In April 2025, AWS experienced a brief outage that affected several exchanges' interfaces. Although on-chain assets were not lost, the feeling of 'my things are not entirely on-chain' is quite disconcerting.

Vanar has a component called Neutron that uses AI and algorithms to compress data, claiming to achieve a compression rate of 500 to 1, turning files into a format called 'seeds' directly on-chain. Your metadata, your documents, your asset proofs no longer rely on any centralized services. This sounds like putting all your eggs in one basket, but if that basket is decentralized itself, then the logic is coherent.

The second thing is that smart contracts can 'understand' data. Kayon is their on-chain reasoning engine, enabling contracts not only to mechanically execute conditional judgments but also to query and analyze stored data. Traditional smart contracts operate on an 'if A then B' logic layer, while Kayon allows contracts to ask: 'What data in this batch meets a certain condition? What are the relationships between them?' This is not just a layer of a large language model shoved onto the chain; it's a reconstructed, verifiable logic layer.

I hold a wait-and-see attitude about whether this thing can truly run. On-chain computing resources are inherently expensive, and reasoning consumes computational power; balancing the two is an engineering problem. But the idea isn't foolish. If it can indeed be achieved, it means on-chain assets possess a certain 'intelligence' rather than just lying there waiting to be called.

The third thing is that they already have functioning products. Virtua Metaverse and the VGN gaming network are products of the Vanar team, and World of Dypians reportedly has over 30,000 active players. This means they are not just painting a picture to attract people; they first have the scene and users, and then go back to build the chain. This order is crucial. Too many public chains boast about their tech stack only to find no one uses it. Vanar does the opposite—they know what game developers need because they themselves are game developers.

I originally wanted to skip over the topic of carbon neutrality because it sounds too much like PR jargon. But I checked their location, and indeed, their nodes run on Google Cloud, utilizing renewable energy. In a market that increasingly values ESG narratives, this is not a detail to overlook.

EVM compatibility means existing Ethereum developers can migrate easily. Unity and Unreal SDKs mean game developers don't have to start from scratch. These are standard actions to reduce migration friction, not worth overemphasizing, but will lead to difficulties later.

As I speak, I have some concerns.

$VANRY has a small market cap, and liquidity in the primary market is dispersed, with not many people discussing it on Telegram and Discord. This means it is still at a very early stage, and price fluctuations can be quite dramatic, with significant room for market makers to pump or dump. If you want to participate, position control is central.

Additionally, the narrative of 'AI reconstructing blockchain' is currently too cumbersome. Every new chain wants to ride the AI wave, but very few can truly combine AI with on-chain computation. Whether Vanar's Neutron and Kayon are genuine skills or just PPT projects needs time to validate.

But the reason I'm willing to look at it a bit longer is: it isn't spinning in the narrative framework of Ethereum; it attempts to solve a specific problem that I can utilize—making small transactions feasible on-chain.

This reminds me of that old man who repairs bicycles. If one day, every five dollars he receives is indeed five dollars, with no middlemen taking a cut, then this chain would be considered successful.

Of course, he may never know what Vanar is. But that doesn't matter. A sign of good infrastructure is that the people using it feel its presence is nonexistent.