Most people understand storage through a simple habit. You copy things. You back up your photos. You mirror your hard drive. You duplicate files across devices because loss feels permanent and recovery feels uncertain. That instinct shaped the early internet and it shaped early decentralized storage too. Copy everything. Replicate it many times. Hope enough copies survive. Over time, that approach has shown its limits. It is expensive, inefficient, and not well suited for the kind of large, long-lived data modern systems actually need. Training datasets. Game assets. Media archives. Machine-generated data that grows quietly but relentlessly. This is the problem space where Walrus Protocol positions itself, not with a loud promise, but with a structural shift in how durability is achieved.

A useful way to picture Walrus is shared custody. Instead of every person owning a full copy of the same album, the album is split into pieces, protected with redundancy, and spread across many participants. Lose a few pieces and nothing breaks. The album can still be reconstructed. This idea is not new. It is the core logic behind erasure coding, a technique long used in distributed systems. What Walrus does is formalize this idea for decentralized environments where trust is minimal and incentives matter. Large binary objects, often called blobs, are broken into smaller units using a two-dimensional erasure coding scheme known as Red Stuff. These fragments, or slivers, are then distributed across specialized storage nodes. Recovery only requires a subset of them, which keeps overhead closer to four or five times the original size instead of full replication across many nodes. That difference may sound abstract, but at scale it changes the economics completely.

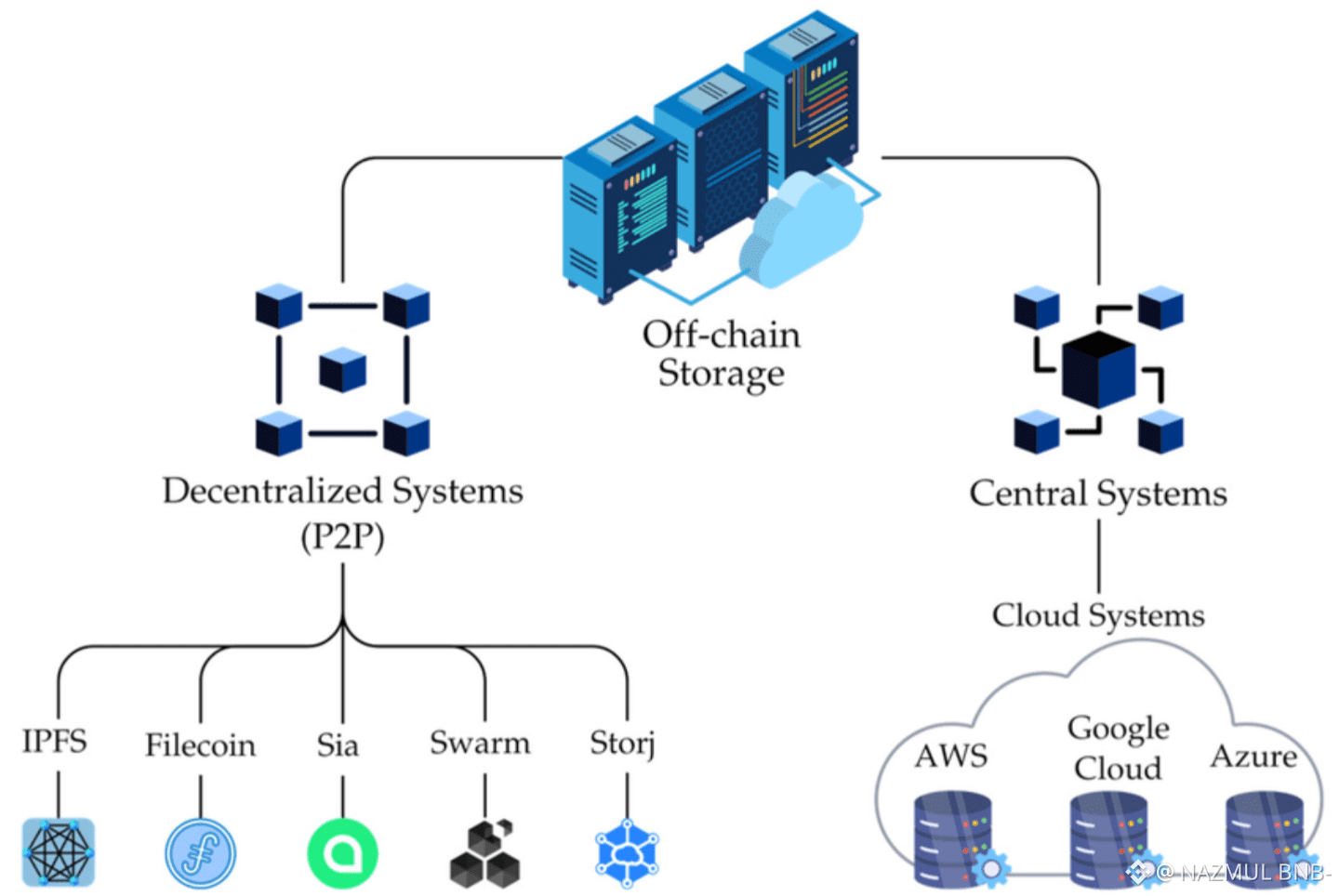

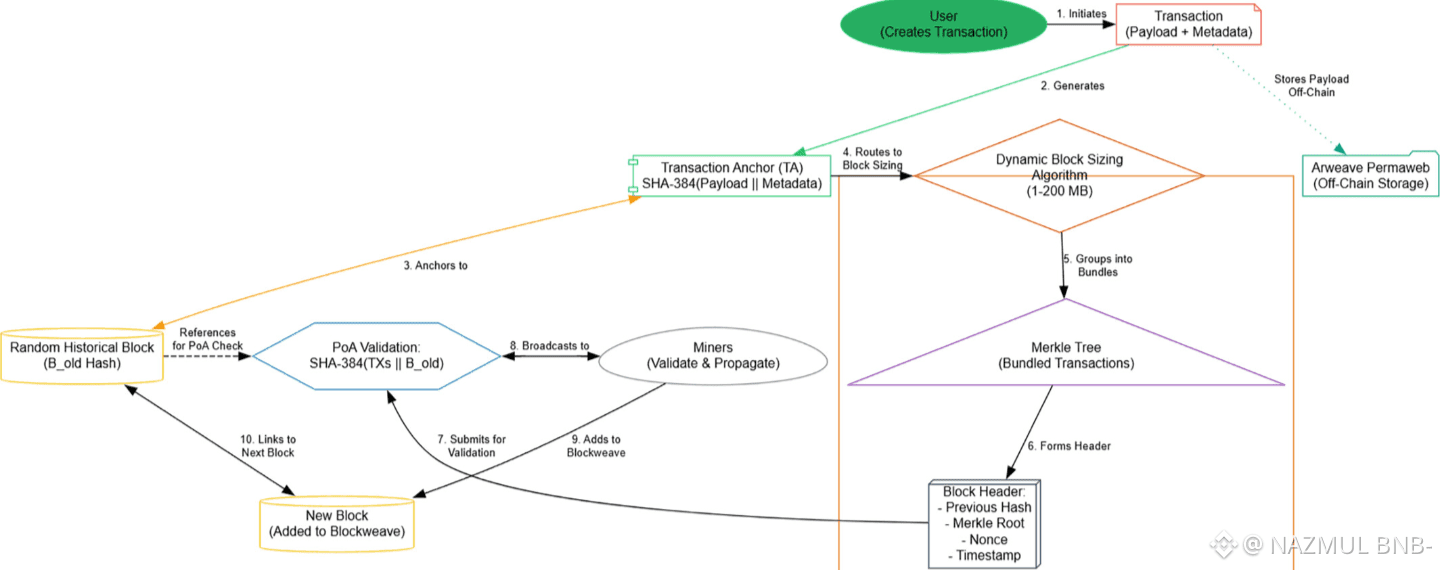

The architecture matters as much as the math. Walrus is built on top of Sui, but Sui does not store the data itself. That separation is intentional. Sui acts as the coordination layer. It handles ownership records, access rules, and availability proofs through smart contracts. Storage nodes hold the actual data fragments off-chain, but their commitments are enforced on-chain. This split keeps the blockchain lean while still making storage behavior accountable. If a node claims to store data, it must prove availability over time. If it fails, economic penalties apply. The chain becomes the referee, not the warehouse. For developers, this design keeps things practical. Data remains large and cheap off-chain. Verification stays transparent and composable on-chain.

This is where the token fits, quietly but deliberately. The WAL token is not framed as a growth engine or a speculative lever. It is a coordination tool. Users pay WAL to store data for fixed durations. Storage providers stake WAL to signal commitment and absorb risk. Governance uses WAL to tune parameters such as rewards and penalties. Most importantly, rewards are tied to actual availability, not abstract participation. Nodes earn by staying online and keeping data retrievable. There is no illusion that the token alone creates value. Its role is to align incentives so the system behaves as intended. When the economics work, data stays available. When they do not, the system should adjust or fail clearly.

From a market perspective, Walrus sits in an interesting middle ground. It is not an experiment in search of a problem, and it is not yet a default choice for global storage. The project has raised roughly $140 million from institutional backers, which signals confidence that long-term data durability is worth serious capital. At the same time, its relevance depends heavily on real usage within the Sui ecosystem. Storage networks tend to compound slowly. They benefit from long time horizons and steady demand, not sudden hype cycles. That puts Walrus in direct comparison with incumbents like Filecoin and Arweave, both of which have years of network effects behind them. Walrus does not try to out-market them. Instead, it differentiates through tighter integration, predictable pricing, and a focus on large, frequently accessed blobs rather than pure archival permanence.

That positioning comes with real risks. Erasure coding systems depend on healthy participation. If too many storage providers leave at once, recovery thresholds can be stressed. A severe market downturn that triggers mass unstaking would test the system’s assumptions. Competition is also unforgiving. Filecoin and Arweave are not standing still, and both continue to refine their own economics and tooling. Walrus does not eliminate these risks. What it does is surface them clearly. The design makes tradeoffs visible instead of hidden. Durability is probabilistic, not magical. Incentives must be maintained, not assumed. In that sense, Walrus feels less like a promise of infinite storage and more like a practical attempt to make shared custody work at internet scale.

In the end, the value of Walrus is not that it invents storage from scratch. It is that it reframes how storage is coordinated. By separating data from verification, by using erasure coding to reduce waste, and by keeping token incentives grounded in behavior rather than speculation, it treats long-term data as infrastructure, not a marketing story. Whether it becomes foundational will depend on adoption, operator diversity, and sustained demand inside Sui-based applications. But the idea it advances is already clear. Durable data does not require endless copies. It requires shared responsibility, enforced honestly, over time.