Security in storage is often described as a lock on a door. But most storage failures do not look like a burglary. They look like confusion. A file is missing when you need it. A link points to something different. Two people download “the same” resource and get different results. In systems that matter, these are not small bugs. They become disputes.

Walrus is designed to reduce that kind of confusion. It is a decentralized storage protocol built for large, unstructured data called blobs. A blob is simply a file or data object that is not stored like rows in a database table. Walrus supports storing and reading blobs, and proving and verifying their availability later. It aims to keep content retrievable even if some storage nodes fail or behave maliciously, a class of failures often described as Byzantine faults. Walrus uses the Sui blockchain for coordination, payments, and availability attestations, while keeping blob contents off-chain. Only metadata is exposed to Sui or its validators.

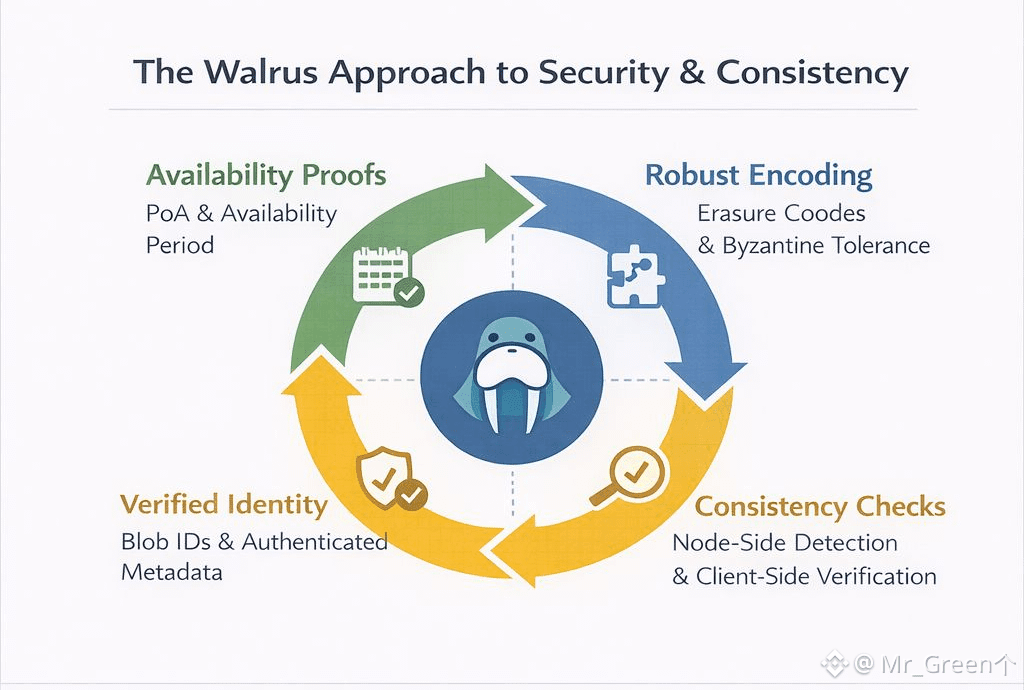

Walrus security begins with a clear moment of responsibility. It defines a Point of Availability, or PoA. PoA is the moment when the system accepts responsibility for maintaining a blob’s availability. The availability period defines how long that responsibility lasts. Both PoA and the availability period are observable through events on Sui. This matters because it turns “we stored it” into a public fact that third parties can check. Before PoA, the client is responsible for ensuring the blob is uploaded correctly. After PoA, the network is responsible for keeping it retrievable for the paid period.

Availability alone is not enough, so Walrus also gives blobs a verifiable identity. Each blob has a blob ID derived from its encoding and metadata. Walrus describes hashing the sliver representation for each shard and building a Merkle tree from those hashes. The root becomes the blob hash, which anchors authenticity checks. In plain language, the blob ID is a fingerprint that readers can use to verify that the data they received matches what the writer committed to. This is important because blobs may be served through optional infrastructure like aggregators and caches over HTTP. Walrus wants fast delivery to be compatible with verification, so a client can still check correctness even when the data comes from an intermediary.

The network’s resilience comes from its encoding and its assumptions. Walrus encodes blobs using erasure coding, splitting a blob into symbols, encoding into more symbols, and distributing the resulting slivers across shards. Walrus describes a storage overhead of about 4.5–5×, which is a cost paid to gain robustness without full replication. The practical benefit is recoverability under partial failure. Walrus describes being able to reconstruct a blob from roughly one-third of the encoded symbols. It also assumes that within each storage epoch, more than two-thirds of shards are managed by correct storage nodes, and it tolerates up to one-third being faulty or malicious. This boundary is where its availability and consistency properties are meant to hold.

But the most subtle part of security is consistency. Walrus treats clients as untrusted. A writer might encode slivers incorrectly, compute hashes incorrectly, or try to upload incorrect metadata. If that happens, you can end up with a dangerous condition: a blob that sometimes decodes and sometimes fails, or worse, a blob that decodes into different values depending on which slivers you gathered. Walrus builds defenses against this at two levels: node-side detection and client-side verification.

On the node side, Walrus describes how honest storage nodes can detect inconsistencies. If a node receives an incorrect sliver or hash, it can attempt to recover the correct data from other nodes and notice the mismatch. When a correct node cannot recover a valid sliver after PoA, it can extract an inconsistency proof. Storage nodes can verify the proof, sign it, and aggregate signatures into an inconsistency certificate that is posted on-chain. Once a blob ID is marked inconsistent, reads resolve to None. This is a strict outcome, but it protects meaning. Walrus would rather fail clearly than allow a blob ID to become an argument.

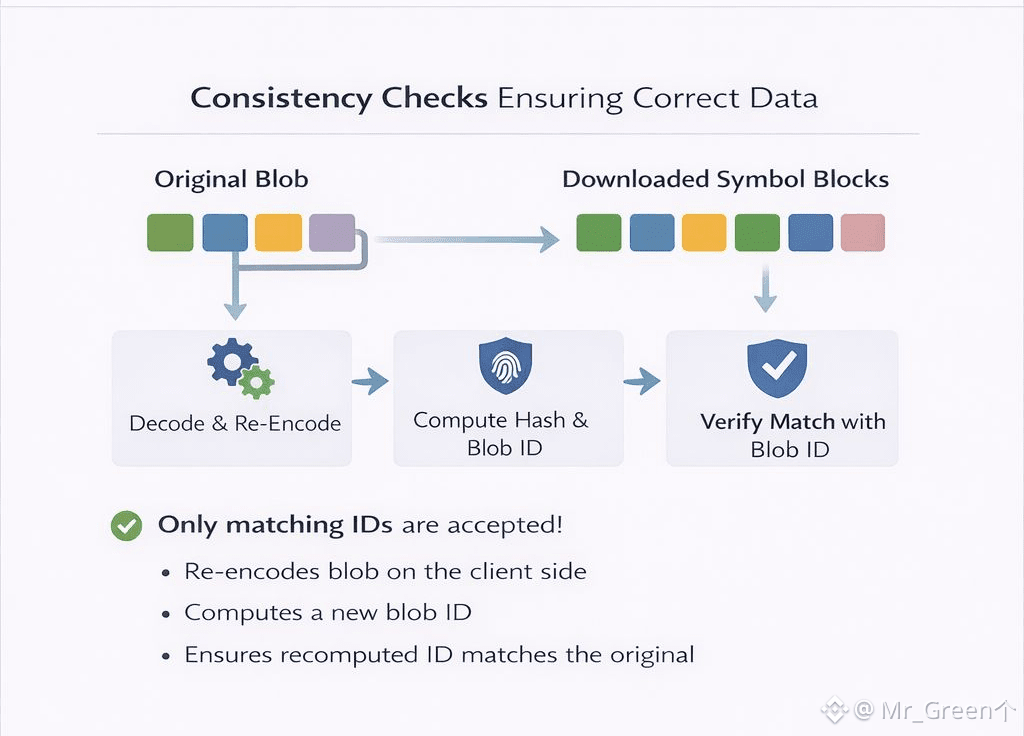

On the client side, Walrus describes two levels of consistency checks during reads: default and strict. The default check is designed to be efficient. The client fetches metadata, requests a subset of primary slivers (Walrus notes a minimum of 334), verifies the sliver hashes against the metadata, decodes the blob, and returns the data only if verification passes. This gives a simple guarantee: if the read succeeds, the client returns the value authenticated by the writer; otherwise, it returns an error.

The strict check is designed for stronger guarantees. After decoding the blob, the client fully re-encodes it, recomputes all sliver hashes and the blob ID, and checks that the recomputed blob ID matches the requested one. The read succeeds only if the IDs match. This extra work matters in edge cases. If a blob was encoded incorrectly, different sets of slivers might decode to different results. The default check ensures correctness when it succeeds, but strict checking ensures that a correct client reading during the blob’s lifetime will always succeed and see the same data, because it verifies the encoding itself is consistent.

Walrus also separates safety from speed in a practical way. It supports Web2 delivery through aggregators and caches, and it is designed to work well with traditional caching and CDNs. But it keeps the verification hooks so that speed does not require blind trust. Readers can authenticate what they receive against the blob ID and metadata, and they can choose stronger checks when the stakes are higher.

The result is a security story that looks less like one big shield and more like layered discipline. Responsibility is time-bound and publicly visible through PoA and availability periods. Identity is anchored by blob IDs and authenticated metadata. Robustness comes from erasure coding and clear Byzantine assumptions. Consistency is protected through both detection (inconsistency proofs and certificates) and verification (default and strict read checks). And failure, when it happens, is designed to be legible: return the verified blob, return an error, or return None when inconsistency is proven.

That is the Walrus approach. It does not ask you to trust storage as a feeling. It asks you to trust storage as a process you can check.