When I look at Vanar, I deliberately ignore the branding, buzzwords, and “next-generation” language that surrounds most Layer-1 blockchains. I try to see it the way I would if I were deciding whether to actually build on it or route users through it. The real question for me isn’t whether it sounds ambitious — it’s whether the system makes sense for how people and markets behave in the real world.

The core problem Vanar is addressing is fairly straightforward: most blockchains still feel like infrastructure built for crypto-native users, not for everyday consumers. Games, entertainment platforms, and brands don’t fail in Web3 because the tech is impossible — they fail because the experience is clunky, slow, confusing, or legally risky. Wallet popups, gas fees, long confirmations, and unclear ownership rules are all friction points that normal users simply won’t tolerate.

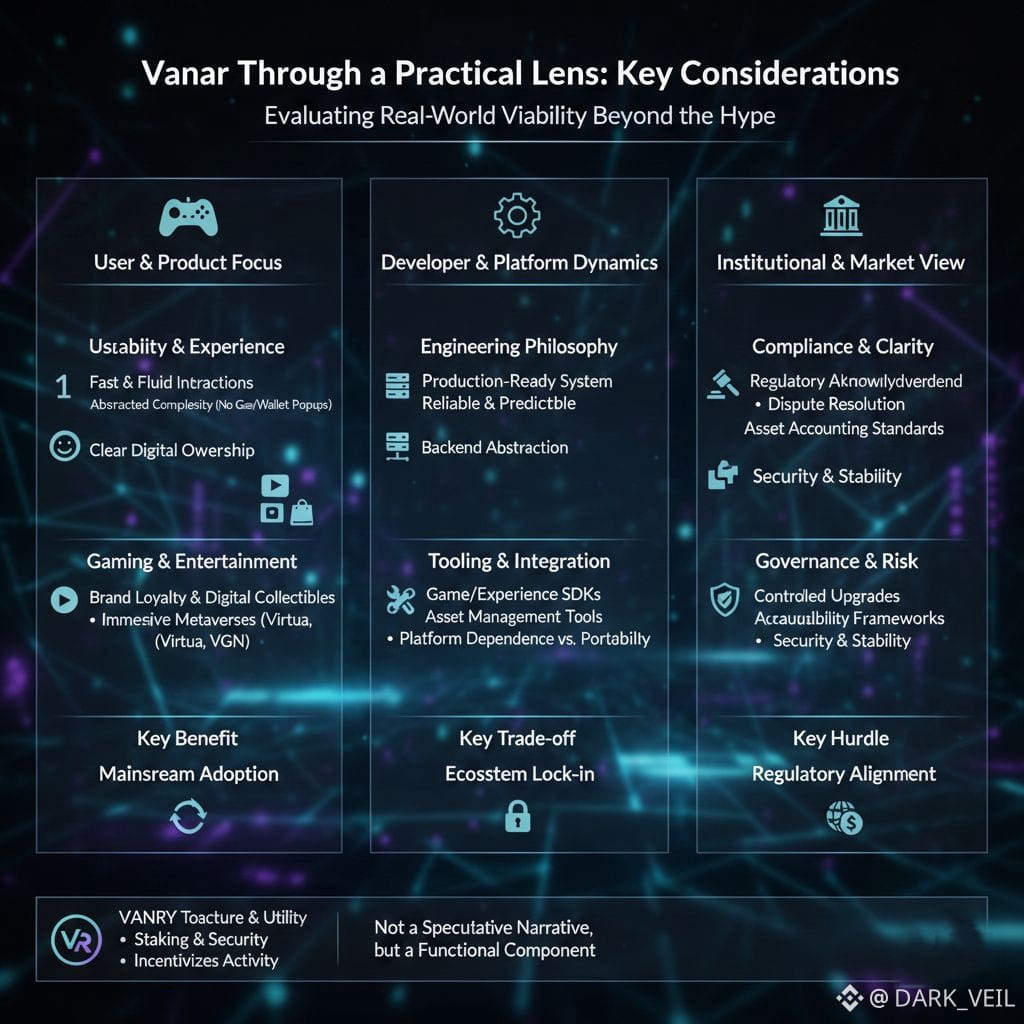

Vanar seems designed with that reality in mind. Instead of chasing ideological purity, it prioritizes usability and predictability. It behaves less like an experimental financial network and more like a production system meant to support real products with real users. That’s not a moral stance — it’s an engineering one. If you want millions of players or consumers interacting daily, the system has to feel boringly reliable.

What stands out to me is how Vanar leans into entertainment, gaming, and brand use cases as first-class citizens rather than side experiments. Products like Virtua Metaverse and the VGN games network aren’t just marketing showcases; they’re stress tests. They force the chain to handle frequent interactions, small transactions, and rich digital assets without breaking the user experience. That pressure shapes design decisions in a way theory never does.

From a normal user’s perspective, this approach matters. Ideally, they don’t feel like they’re “using a blockchain” at all. Things load quickly, actions feel instant, and ownership or rewards are simply part of the product — not a technical hurdle. To achieve that, the system often absorbs complexity on the backend. That can mean abstracting fees, simplifying accounts, or bundling services that would otherwise live off-chain. These choices improve usability, but they also introduce responsibility. Someone has to manage that complexity, and that someone is usually the platform or the builder.

For developers, the appeal is speed and focus. If the chain already supports the kinds of data and interactions common in games or immersive digital environments, teams can spend more time on the product and less on plumbing. The trade-off is dependence. The more a builder relies on chain-specific tools, the harder it becomes to migrate later. That’s not inherently bad — it just means teams need to be honest about whether they’re optimizing for fast delivery or long-term portability.

When I think about institutions or serious market participants, the evaluation becomes more conservative. Institutions care less about novelty and more about clarity: who controls upgrades, how disputes are handled, how assets are accounted for, and how risk is managed. Vanar’s structure appears to acknowledge these concerns by treating compliance, accountability, and settlement as realities rather than inconveniences. That makes it easier to imagine controlled, limited integrations — though full institutional adoption always depends on governance maturity and regulatory alignment over time.

The VANRY token, in this context, feels more like infrastructure than a narrative. Its role is to pay for activity, secure the network through staking, and coordinate incentives across users, builders, and validators. Whether that works long-term depends less on speculation and more on actual usage. Tokens only hold structural value if they’re consistently needed for real activity and if the security model remains credible as the network grows.

I don’t see Vanar as a universal solution or a revolution. I see it as a focused attempt to make blockchain infrastructure usable for consumer-facing products that already exist in the real world games, digital experiences, brand ecosystems — without forcing them to adopt crypto ideology wholesale. That focus brings advantages, but it also narrows the scope and increases execution risk. Delivering smooth consumer experiences at scale is hard. Operating in regulated environments is harder.

If Vanar succeeds, it won’t be because it promised a new world, but because it quietly fits into the one we already have. And if it struggles, it will likely be for the same reason most pragmatic systems struggle: adoption takes longer, coordination is messy, and real users are far less forgiving than whitepapers assume.