I first noticed the shift not in a headline or a product launch, but in the behavior of systems that no longer waited for anyone to check on them. Capital was moving with a kind of quiet confidence, not aggressively, not defensively, but continuously. Decisions were being made in small increments, often invisible unless you knew exactly where to look. That was the moment it became clear to me that on-chain automation was no longer an experimental layer sitting on top of markets. It was becoming the market’s operating rhythm. Thinking about AT in that context requires stepping back from token mechanics and asking a more basic question about what the next phase of automation actually demands from infrastructure, incentives, and governance.

From an institutional research perspective, the story of on-chain automation has always been less about intelligence and more about coordination. Traditional finance spent decades optimizing coordination through centralized systems, legal contracts, and human oversight. Blockchain systems attempted to replace parts of that stack with code and transparency, but for a long time they still relied on human pacing. Decisions were episodic. Risk was managed in batches. Automation existed, but it was constrained by execution environments that were never designed for continuous, autonomous behavior. The current phase feels different. Automated strategies are no longer helpers. They are primary actors, operating across liquidity, execution, and risk management without waiting for human intervention.

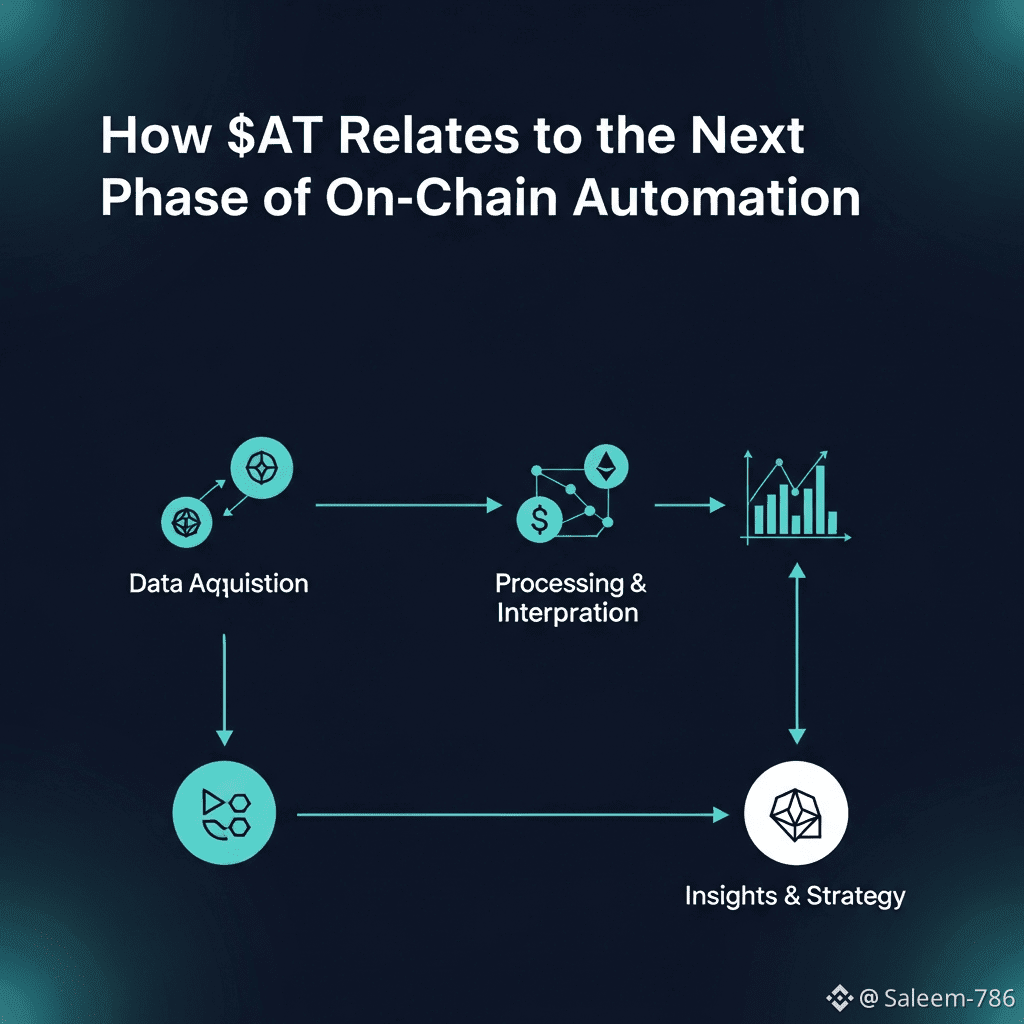

$AT sits inside this transition not as a promise of smarter automation, but as an economic component of systems that assume automation is persistent. What stands out is not the presence of agents, but the assumption that they will be there all the time. That assumption reshapes everything. Fee models matter differently when transactions are frequent and small. Governance matters differently when behavior emerges from interaction rather than instruction. Risk management matters differently when exposure is adjusted continuously instead of periodically. From a regulated finance lens, this begins to resemble the shift from discretionary trading to high-frequency infrastructure decades ago, except this time the coordination layer is public and programmable.

One of the subtler points that emerges when studying systems tied to AT is that automation at this stage is less about decision quality and more about execution reliability. Institutions learned long ago that even the best models fail if execution is inconsistent. Slippage, latency, and unpredictable state changes introduce errors that compound over time. On-chain systems historically tolerated these imperfections because humans could adapt around them. Autonomous systems cannot. They either incorporate the environment into their logic or abandon it. The relevance of AT, therefore, is tied to whether the surrounding infrastructure makes automation economically viable over long horizons rather than momentary opportunities.

There is also an important distinction between automation and autonomy that often gets blurred. Automation executes predefined actions. Autonomy adapts behavior based on observed conditions. The latter introduces emergent risk. When many autonomous actors operate under similar constraints, they can converge on the same actions without coordination. This is not malicious behavior. It is rational behavior under shared incentives. From an institutional perspective, this looks very similar to correlation risk in traditional markets, except that here it manifests at machine speed. Any system where AT plays a role in incentives or access must contend with this reality. The token does not cause convergence, but it participates in the incentive structure that shapes it.

Governance becomes the most underappreciated part of this discussion. In regulated environments, governance exists to slow systems down, to introduce deliberation and accountability. On-chain automation moves in the opposite direction. Decisions happen continuously. By the time governance reacts, behavior has already adapted. This does not mean governance is irrelevant. It means governance must shift upstream. Parameters, constraints, and incentive curves matter more than reactive votes. The way AT is embedded in governance frameworks, whether directly or indirectly, influences not just outcomes but the kinds of behaviors that are economically rational in the first place.

Another trade-off worth noting is accessibility versus effectiveness. Public, permissionless systems are often celebrated for openness, but automation-heavy environments reward precision and depth. Anyone can deploy a strategy, but not every strategy survives. This creates a gap between formal access and practical influence. From an institutional viewpoint, this is not inherently negative, but it does challenge narratives that equate openness with egalitarian outcomes. AT exists within that tension. It can lower barriers to participation at the protocol level while still producing highly selective economic outcomes.

Risk, in this next phase, becomes quieter rather than louder. Instead of dramatic failures, there are coordinated withdrawals, liquidity thinning, and sudden changes in market microstructure. These are harder to detect and harder to explain after the fact. Transparency helps, but transparency does not guarantee comprehension. Analysts and regulators alike will need to develop new tools to interpret behavior that emerges from automated interaction rather than explicit intent. Any long-term evaluation of AT has to consider whether the systems around it make these dynamics observable and auditable, not just efficient.

What gives me pause, and also some confidence, is that the most resilient financial infrastructures historically were not the ones that promised the most innovation, but the ones that understood their own limits. Systems that acknowledged correlation risk, operational risk, and incentive misalignment early tended to adapt better over time. The role of AT in the next phase of on-chain automation will be judged less by short-term adoption and more by whether it supports environments where automated actors can fail in controlled ways rather than catastrophically.

Stepping back, it becomes clear that the next phase of on-chain automation is not about replacing human judgment, but about relocating it. Humans are no longer in the execution loop. They are in the design loop. That includes deciding what kinds of automation are acceptable, what kinds of risks are tolerable, and what kinds of behaviors should be discouraged economically. AT is one piece of that design space. Its relevance depends on whether it aligns incentives toward sustainable coordination rather than fragile efficiency.

There is a temptation to look for clear conclusions, to label this shift as positive or negative. Institutional history suggests that such labels rarely hold. Automation increases efficiency and exposes new failure modes at the same time. The real question is whether systems evolve fast enough to manage the risks they create. In that sense, AT is less a bet on technology and more a bet on governance and restraint. The next phase of on-chain automation will not announce itself loudly. It will feel like markets simply stop waiting for us.