Starting from an uncomfortable assumption

Most distributed systems fail not because of rare catastrophes, but because of ordinary instability. Machines reboot. Networks degrade. Operators make cost‑driven decisions. In decentralized infrastructure, these conditions are not anomalies—they are the baseline. Any protocol that assumes stable participation is already misaligned with reality.Walrus begins from a more pragmatic assumption: nodes will leave. Storage providers will disconnect temporarily or permanently. Hardware will fail. Bandwidth will fluctuate. Instead of designing around ideal uptime, Walrus treats churn as the default operating environment.This framing is neither pessimistic nor novel. It is simply realistic. The question worth examining is how well this assumption holds up once the system is stressed by real usage rather than controlled simulations.

What churn actually means in practice

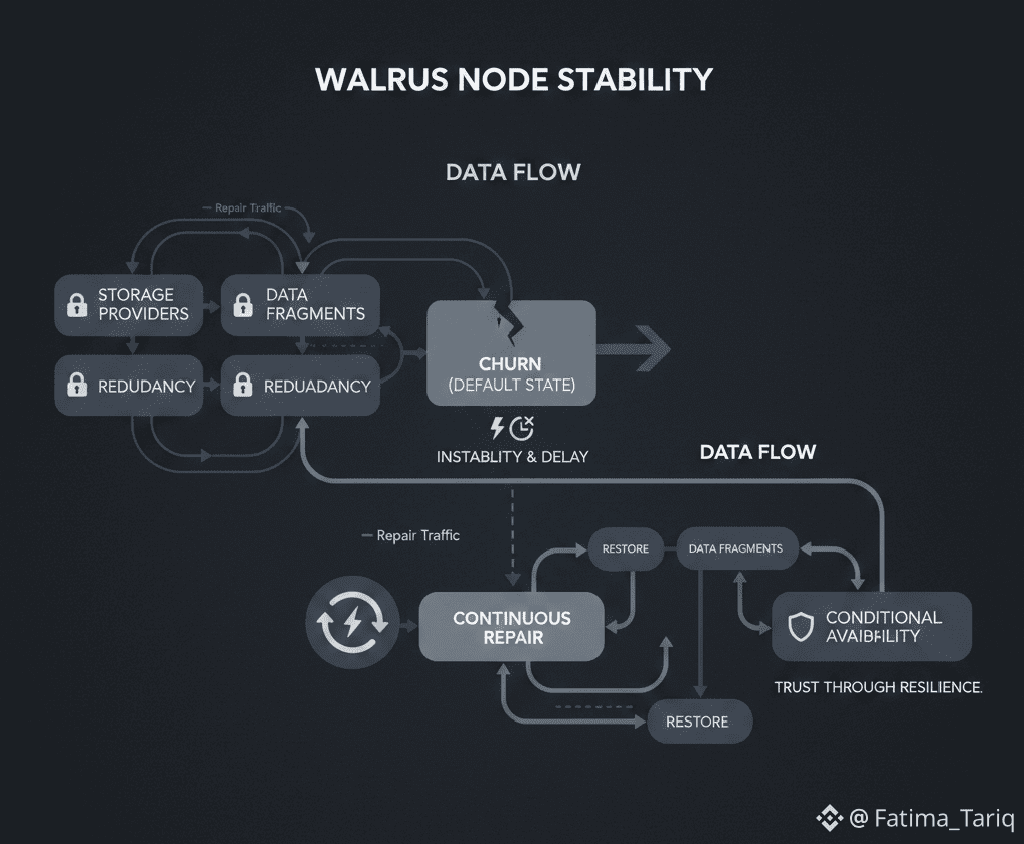

Churn is often described abstractly as nodes joining and leaving a network. In operational terms, it manifests as missing fragments, delayed responses, and uneven data distribution. For a storage protocol, churn directly threatens availability and durability.Walrus addresses this through a combination of erasure coding, redundancy thresholds, and continuous repair. Data is split into fragments and distributed across many nodes. As long as a sufficient subset remains reachable, data can be reconstructed. When fragments disappear due to churn, the system initiates repair to restore redundancy.This approach acknowledges that loss is inevitable. Durability is not achieved by preventing failure, but by compensating for it quickly enough.

Repair as a permanent workload, not an exception

In Walrus, repair is not a background task triggered occasionally. It is a persistent workload. As nodes churn, fragments are lost continuously, and redundancy must be re‑established continuously.This design choice has important implications. Repair traffic consumes bandwidth, storage I/O, and coordination effort. Unlike user reads, repair activity is invisible to most users, yet it often dominates network usage during periods of instability.The system must therefore balance two competing goals: serving user requests promptly and maintaining sufficient redundancy to prevent irreversible data loss. Under light churn, this balance is easy to maintain. Under heavy churn, the trade‑off becomes visible.

When churn accelerates non‑linearly

One of the defining characteristics of churn is that its impact is rarely linear. A small increase in node instability can trigger a disproportionate increase in repair activity. Each missing fragment requires reconstruction, which itself depends on retrieving other fragments that may also be under stress.As repair frequency increases, bandwidth contention grows. Repairs take longer. The window for recovery narrows. This feedback loop does not imply system failure, but it does impose practical limits on scale and responsiveness.Walrus mitigates this through conservative redundancy thresholds and proactive repair, but it cannot eliminate the underlying dynamic. The protocol manages churn; it does not neutralize it.

Overlapping reads and repairs under churn

Churn rarely occurs in isolation. It often coincides with network congestion, cost‑driven throttling, or regional outages. During these periods, user reads and repair operations overlap, competing for the same resources.Reads are bursty and user‑driven. Repairs are persistent and system‑driven. When both intensify simultaneously, contention emerges. Reads slow down, prompting retries. Retries increase load, further delaying repairs. Meanwhile, delayed repairs increase the risk of falling below recovery thresholds.This interaction is subtle and difficult to observe externally. Users may experience inconsistent latency without understanding the cause. From the system’s perspective, it is a predictable outcome of designing for churn rather than pretending it does not exist.

Conditional availability as a design outcome

Walrus does not offer absolute availability. It offers conditional availability: data can be retrieved if enough fragments are reachable within acceptable time and cost constraints. Churn directly affects those conditions.Under moderate churn, availability remains high. Under severe churn, availability degrades gracefully rather than catastrophically. Some reads succeed, others stall, and repair continues in the background.This behavior is often misunderstood as unreliability. In reality, it reflects a system that prioritizes long‑term durability over short‑term consistency. Availability becomes a probability shaped by current network conditions, not a guarantee enforced by centralized control.

Human behavior under instability

Churn is amplified by human behavior. When storage providers experience instability, they may disconnect intentionally to avoid cost overruns. When users encounter slow reads, they refresh or retry. When developers observe intermittent failures, they implement aggressive retry logic.These responses are rational, but they intensify load during the worst possible moments. Each retry generates additional fragment requests. Each shortcut increases coordination overhead. The system must absorb not only technical failure, but predictable human reactions to uncertainty.Walrus does not attempt to police these behaviors at the protocol level. Instead, it relies on redundancy and repair to absorb them. This is a pragmatic choice, but it means that real‑world performance will always reflect the combined behavior of humans and machines.

Privacy and decentralization during churn

Churn interacts with privacy in complex ways. Fragment distribution and opaque blobs reduce centralized visibility, even when nodes leave and rejoin. This strengthens censorship resistance and limits single‑party control.At the same time, high churn can create observable patterns. Repair traffic increases. Certain fragments become hotspots. While content remains hidden, metadata exposure grows under sustained instability.Decentralization also slows intervention. There is no central operator to halt repairs, reroute traffic, or prioritize recovery. This protects the system from coercion, but it also means recovery is driven by incentives and coordination rather than command.

Strengths grounded in realism

Walrus’s greatest strength is that it does not treat churn as a pathological edge case. It assumes instability and builds around it. Erasure coding, continuous repair, and conservative redundancy thresholds reflect a system designed for imperfect conditions.This realism distinguishes infrastructure protocols from more speculative designs. Walrus does not promise seamless performance under all circumstances. It promises that data loss becomes unlikely as long as the system remains active and sufficiently resourced.That is a narrower promise—but a more honest one.

Where the compromises appear

As Walrus scales, churn‑related costs will rise. Repair traffic will consume more bandwidth. Operator incentives will matter more. Users will encounter variability in performance that cannot be smoothed away without sacrificing decentralization.These compromises are not design failures. They are the result of choosing openness, neutrality, and resilience over predictability and control. Any system that claims otherwise is shifting complexity somewhere less visible.

A measured conclusion

Churn is not a problem to be solved once. It is a condition to be managed continuously. Walrus approaches node instability with a sober understanding of distributed systems: failure is normal, recovery is ongoing, and availability is conditional.Evaluated on these terms, Walrus offers a credible model for decentralized storage under real‑world conditions. Its handling of churn reflects an acceptance of trade‑offs rather than an attempt to erase them.For infrastructure, that acceptance is not a weakness. It is the foundation of long‑term trust.