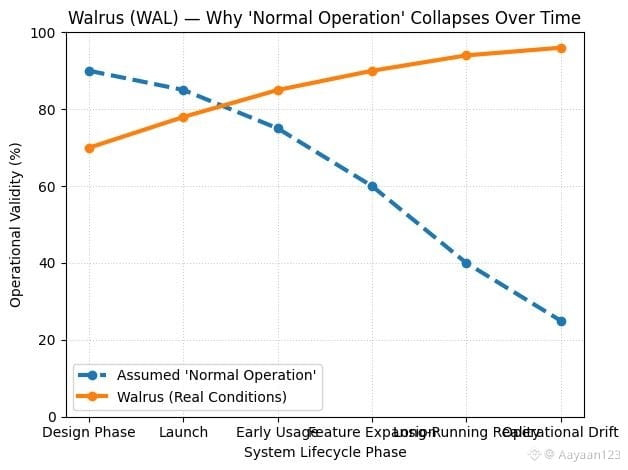

The first thing I tried to do when looking at Walrus was simple. I wanted to understand what “normal operation” even means for the protocol. Not stress conditions. Not edge cases. Just the baseline. The everyday state where nothing is going wrong, nothing is being exploited, and the system is doing exactly what it was designed to do. That exercise lasted about five minutes before it completely collapsed.

The first thing I tried to do when looking at Walrus was simple. I wanted to understand what “normal operation” even means for the protocol. Not stress conditions. Not edge cases. Just the baseline. The everyday state where nothing is going wrong, nothing is being exploited, and the system is doing exactly what it was designed to do. That exercise lasted about five minutes before it completely collapsed.

Not because Walrus is broken, but because the idea of “normal” doesn’t really apply.

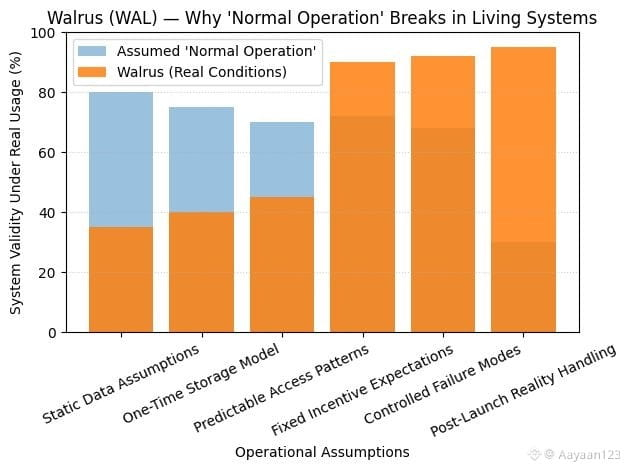

Most systems are built around stable assumptions. There is a clear user, a predictable workload, a known pattern of access, and a fairly narrow definition of success. A payment network moves money. A chain settles transactions. A storage layer holds files. Walrus doesn’t fit neatly into any of those boxes. It’s a data availability and storage system that assumes the shape of the workload is constantly changing, that users may not even know how their data will be consumed later, and that access patterns can shift without warning. In that context, normal operation stops being a steady state and starts becoming a moving target.

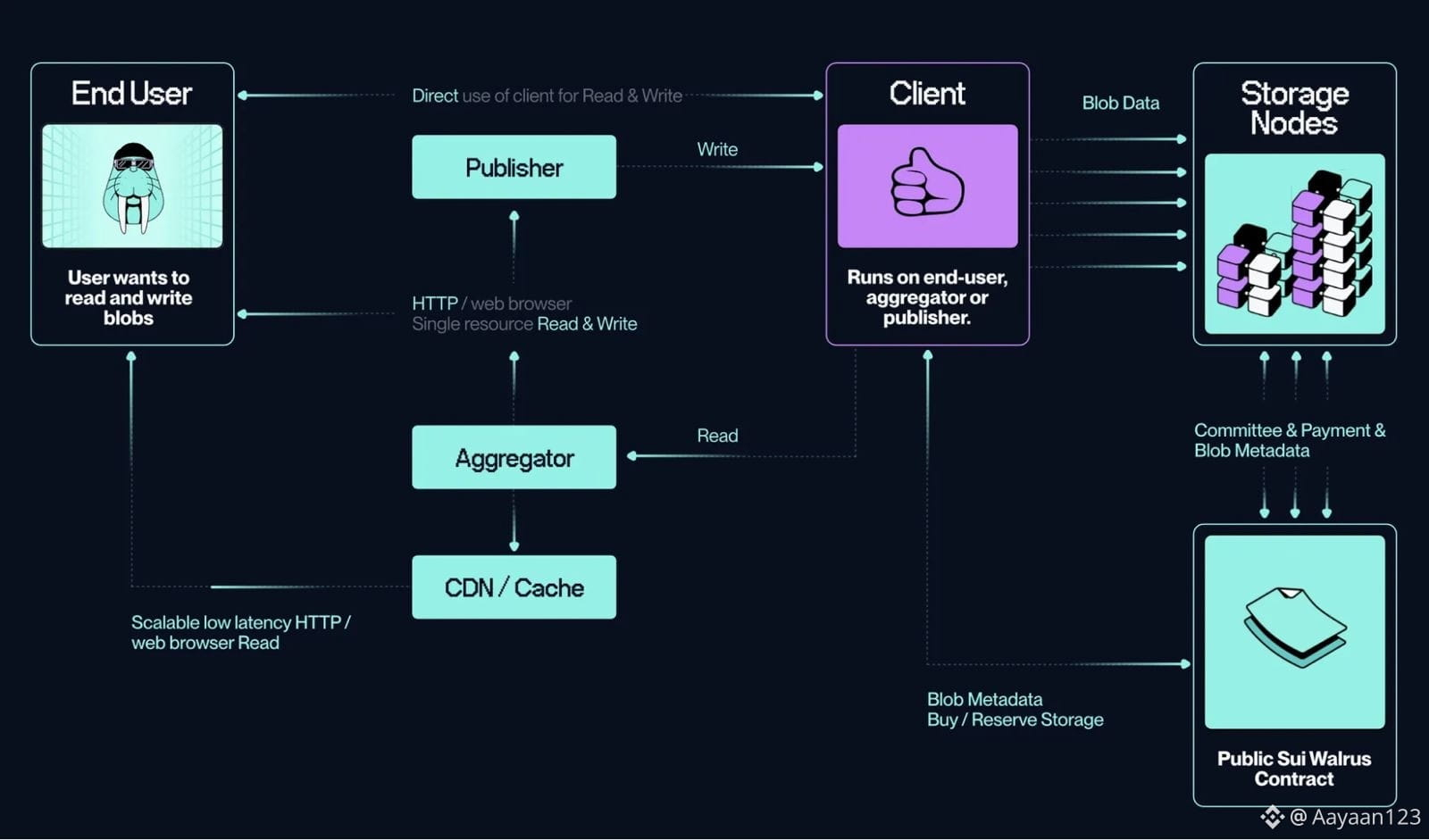

At first glance, you might think normal operation simply means data is being uploaded, stored, and retrieved. But even that framing breaks down quickly. Who is uploading the data? Is it a user, an application, an autonomous system, or another chain? Is the data static or continuously updated? Is it being read once or referenced thousands of times by downstream systems? Walrus doesn’t privilege one of these cases over the others. It’s designed to accommodate all of them, which means there is no single behavior pattern you can point to and call “typical.”

This becomes even more complicated when you consider what Walrus is trying to protect against. In many systems abnormal behavior is defined as malicious behavior. Spam. Attacks. Exploits. In Walrus, high-volume access or sudden spikes aren’t necessarily hostile. They might be the expected outcome of a new application going live, an AI model querying large datasets, or a network synchronizing state across regions. What looks like stress from the outside can be healthy demand from the inside. So even load itself isn’t a reliable indicator of something being wrong.

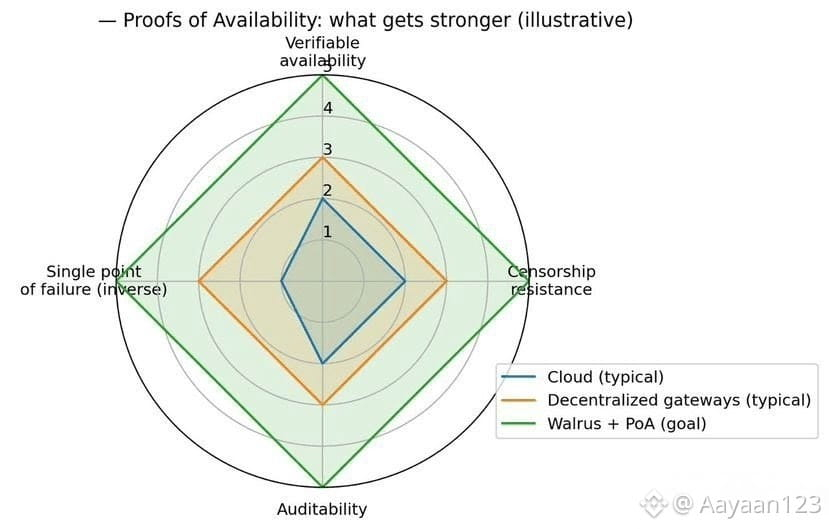

The more I looked, the clearer it became that Walrus is built around a different assumption: that unpredictability is the default, not the exception. Instead of trying to smooth behavior into a narrow operational band, the system is structured to remain correct even when usage patterns swing wildly. That shifts the focus away from defining “normal” and toward defining “acceptable.” As long as data remains available, verifiable, and resistant to censorship or loss, the system is doing its job, regardless of how strange the traffic looks.

This is where traditional mental models fail. We’re used to thinking in terms of steady-state performance. Average throughput. Typical latency. Baseline utilization. Walrus challenges that by making correctness more important than consistency. It doesn’t promise that usage will look the same tomorrow as it does today. It promises that whatever happens, the data will still be there and still be provable. That’s a subtle but profound shift.

What really drove this home for me was thinking about how Walrus fits into emerging workloads. AI systems don’t behave like humans. They don’t browse data casually or access things in predictable intervals. They pull massive amounts of information, sometimes repeatedly, sometimes in bursts, sometimes in ways that look pathological from a traditional network perspective. The same is true for autonomous agents, large-scale indexing systems, and cross-chain infrastructure. If Walrus tried to define normal operation based on human-like usage, it would fail immediately. Instead, it treats all of these behaviors as potentially valid.

There’s also a deeper philosophical layer here. By refusing to define a narrow “normal,” Walrus avoids embedding assumptions about who deserves access and how. In many systems, optimization choices implicitly favor certain users. Light users over heavy ones. Predictable ones over chaotic ones. Walrus’s design resists that bias. It doesn’t try to guess intent. It focuses on guarantees. If the rules are followed, the system responds. That neutrality is uncomfortable, because it removes the comforting idea that someone is in control of what “should” happen.

This discomfort becomes especially visible when people ask whether Walrus can be considered stable. Stability usually implies sameness. Repetition. Familiar patterns. Walrus offers a different kind of stability: invariance under change. The behavior around the edges can vary wildly, but the core properties don’t move. Data remains accessible. Proofs remain valid. The system doesn’t degrade into special cases just because usage doesn’t fit a preconceived mold.

Trying to pin down normal operation also exposes how Walrus blurs the line between infrastructure and environment. It’s not just a service you call; it’s a substrate other systems rely on. When something breaks downstream, it’s tempting to look upstream and ask whether Walrus was behaving normally. But that question assumes a separation that doesn’t always exist. If an application is designed to push the limits of data access, Walrus’s role is not to normalize that behavior but to withstand it. Normality, in that sense, is defined by resilience, not calmness.

What’s interesting is how this reframes operational risk. In traditional systems, risk is often tied to deviation from expected behavior. In Walrus, risk is tied to violations of guarantees. As long as the cryptographic and economic rules hold, the system is functioning correctly, even if the surface-level metrics look chaotic. That’s a much harder thing to reason about, but it’s also more honest in a world where workloads are increasingly machine-driven and unpredictable.

After a while, I stopped trying to define normal operation and started asking a different question: what would failure look like? Not slowdowns or spikes, but actual failure. Data becoming unavailable. Proofs no longer verifiable. Access becoming arbitrarily restricted. Those are the conditions Walrus is designed to prevent. Everything else is noise. That realization flipped the analysis entirely. Normal operation isn’t a state you observe; it’s the absence of certain failures.

This perspective also explains why Walrus can feel unsettling to people used to cleaner narratives. There’s no neat dashboard that tells you everything is “fine.” There’s no single metric that captures health. Instead, there’s a set of properties that either hold or don’t. That’s a more abstract way of thinking, and it demands trust in the design rather than comfort in familiar patterns.

In the end, my attempt to define normal operation didn’t fail because Walrus is poorly specified. It failed because Walrus rejects the premise. It’s built for a world where data usage is inherently irregular, where machines act alongside humans, and where future applications will look nothing like today’s. In that world, normal isn’t something you can define in advance. It’s something that emerges moment by moment, bounded only by the guarantees the system refuses to break.

And maybe that’s the real insight. Walrus isn’t trying to make decentralized data feel orderly. It’s trying to make it reliable, even when order disappears.