@Walrus 🦭/acc Operational planning for Walrus reconfiguration windows sounds like a niche job until you’re the person who has to explain—without drama—why a storage network needs “windows” at all. With Walrus, those windows aren’t a habit borrowed from old IT playbooks. They’re baked into how the protocol stays decentralized while still behaving like something people can actually rely on.

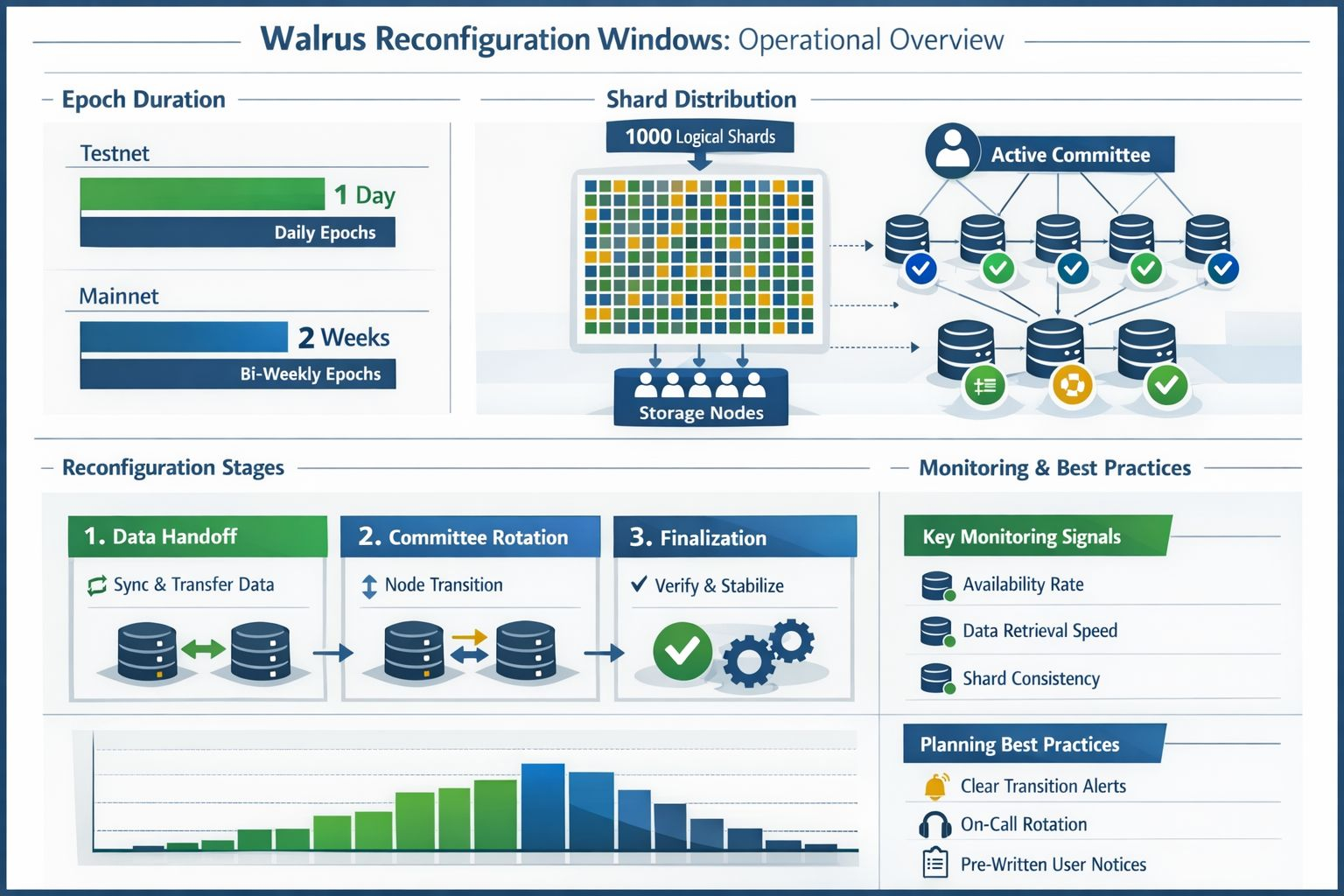

Walrus runs in epochs: fixed periods where an active committee of storage nodes is responsible for holding and serving data. The network keeps a fixed set of logical shards (currently 1000), and responsibility for those shards sits with whoever is in the active committee for that epoch. On Testnet, epochs are one day. On Mainnet, they’re two weeks. That difference matters operationally, because it changes the feel of risk. Daily transitions teach you fast. Two-week transitions make it easier to grow complacent—and then get surprised.

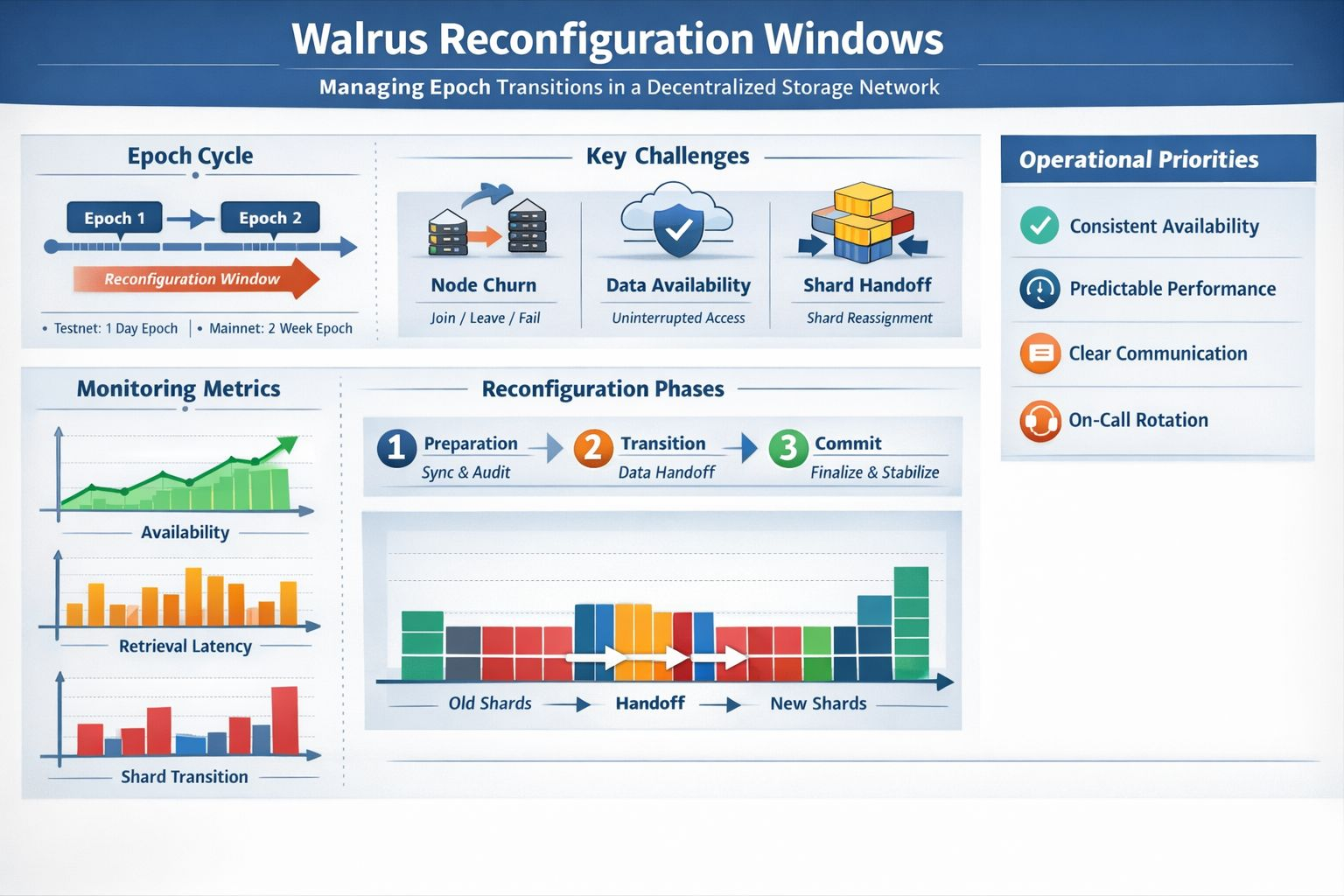

The part people often miss is that Walrus isn’t “just storage.” It’s blob storage with protocol-level guardrails that try to make storing large files both efficient and verifiable in a permissionless setting. The core paper frames the problem plainly: if you want decentralization, you have churn—nodes join, leave, and fail—and you still need availability to hold through those shifts. Walrus’ answer isn’t to pretend churn won’t happen. It’s to design for it, with a multi-stage epoch change meant to keep blobs continuously available even as the committee changes.

That protocol detail is exactly why “reconfiguration windows” are suddenly a real topic instead of an academic one. Walrus Mainnet is positioned as a production storage network, not a lab experiment, and developers are being asked to build against it like it’s dependable infrastructure. When you move from “interesting design” to “people are uploading data that matters,” the operational edge cases stop being theoretical. A messy epoch boundary is no longer a footnote; it’s a user-facing event.

It also helps explain why the broader culture around operations has shifted. In a lot of teams, the old default was to bundle changes and hide them inside late-night maintenance windows. But distributed systems have a way of punishing that instinct. When a transition touches availability, correctness, economics, and membership all at once, it becomes hard to tell what actually went wrong. Walrus makes this even more pronounced because the epoch boundary is already a coordinated change in who is responsible for data. The protocol is doing something meaningful at that moment—committee membership can change at an epoch transition, and the system has a staged mechanism to manage that safely.

So the practical planning question becomes: how do you treat an epoch transition like a normal, controlled part of the product rather than a scary ceremony? The most useful mental shift I’ve seen is to stop calling it “internal.” In Walrus, the reconfiguration window is a customer moment. If uploads slow down or retrieval feels uneven, nobody experiences that as “a routine epoch change.” They experience it as a service that suddenly got unreliable. And because Walrus is designed for storing large blobs, the user impact can be very tangible: an app that can’t fetch media quickly feels broken, even if the underlying protocol is still technically meeting its guarantees.

This is where Walrus’ technical design should shape your operational habits. The paper emphasizes efficient recovery under churn and the goal of uninterrupted availability during committee transitions. That’s not just a nice claim. It’s a hint about what to watch. A well-run reconfiguration window is one where your monitoring and incident triggers map to the protocol’s promises: availability during the handoff, consistency of reads, and predictable performance as shard responsibility shifts. If those signals aren’t visible, people end up guessing—and guessing is what turns a minor wobble into a full-blown incident.

There’s another Walrus-specific nuance that makes planning feel more urgent today than five years ago: the protocol is trying to make decentralized storage economically and operationally viable at scale, not just possible. That shows up in its focus on erasure coding and recovery efficiency, and in how it coordinates nodes across epochs. If Walrus succeeds, it changes what builders expect from decentralized storage. The bar rises from “eventually available” to “boringly available.” And the way you get boring is by taking the epoch boundary seriously—treating it as a first-class event in the life of the network.

When I think about what makes reconfiguration planning work in practice, it comes down to a quiet kind of discipline. You avoid stacking optional changes on top of an epoch transition because the transition already has enough moving parts. You rotate on-call so knowledge isn’t trapped in one tired person. You write the “what users will notice” message ahead of time, not because you’re pessimistic, but because clarity is hardest to produce when you need it most. None of that is glamorous. But it aligns with the point Walrus is making: decentralization is dynamic. Committees change. Shards move. The system stays available anyway—if we respect the moment where it has to do the most work.