The Federal Reserve's December 2025 interest rate decision was less a "rate cut" and more a "policy declaration" setting the tone for global markets over the next 1-2 years. The meeting not only lowered the federal funds rate by 25 basis points, but also, through a significantly divided vote, the resumption of short-term Treasury bond purchases, and the dot plot indicating "one rate cut each in 2026 and 2027," clarified the core direction of "slow-paced easing + liquidity restoration." This direction directly ruled out the possibility of "massive stimulus" and locked in the core characteristic of the market outlook—a departure from a broad-based rally, entering a structural market that only recognizes "certainty."

The core of the resolution: all signals point to "slow" and "steady".

To understand the logic behind the market outlook, we must first clarify the three key hard facts of the December decision, which together form the basis of all subsequent analysis:

First, while the interest rate cut was implemented, significant disagreements remained, and the pace of easing was strictly constrained. The Federal Reserve ultimately lowered the interest rate from 3.75%-4.00% to 3.50%-3.75% by a vote of 9 to 3.50%. Market reports indicate that the dissenting votes included those advocating for a larger rate cut as well as those hoping to hold rates steady. This disagreement is far from minor; it demonstrates a significant internal debate within the Fed regarding the "scale of easing," effectively eliminating the possibility of aggressive rate cuts.

Second, resuming short-term bond purchases is about "repairing the pipeline," not "flooding the market with liquidity." The implementation guidelines accompanying this resolution emphasize that sufficient reserves will be maintained through necessary open market operations such as short-term Treasury bond purchases and repurchase agreements. Chairman Powell repeatedly stressed in the press conference that these operations are "reserve management operations," completely different from the quantitative easing (QE) during the pandemic—QE was to stimulate the economy, while this bond purchase is to repair the liquidity transmission mechanism of the banking system, ensuring that funds flow smoothly to the real economy.

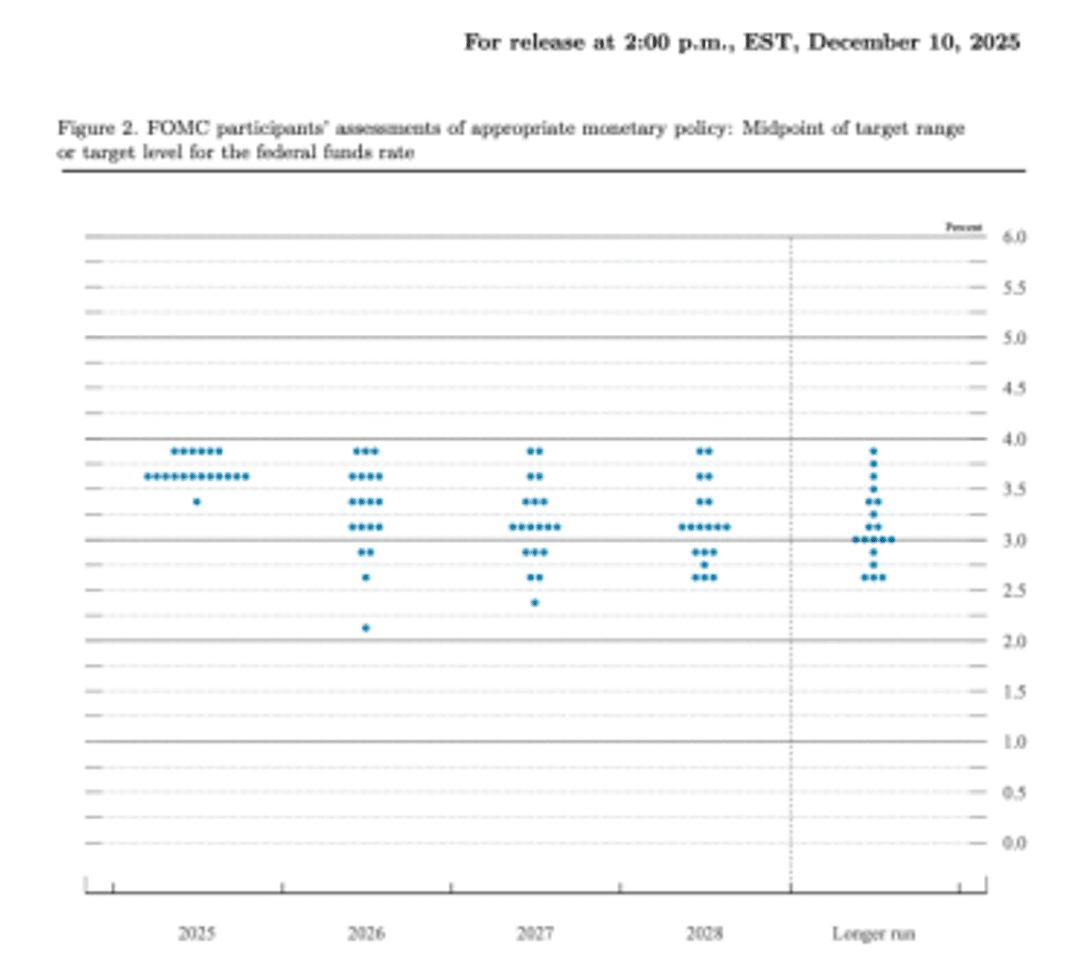

Third, the dot plot sets the tone for "ultra-slow rate cuts": a cumulative reduction of approximately 50 basis points by 2027. This is one of the most crucial signals. The currently released dot plot does indeed point to a further slight decline in the federal funds rate in 2026-2027, with a cumulative additional reduction of approximately 50 basis points throughout the year. The implied path and pace are significantly slower than previous relief-style rate cut cycles. Looking back at history, even the preventative rate cuts of 1995 achieved three consecutive reductions of 25 basis points each, a much faster pace than this. This means that over the next two years, funding costs will "decline slowly," rather than "plummet rapidly."

MSX Research Institute believes that the core of this decision is not "easing," but rather "controlled and moderate improvement": it aims to alleviate downward economic pressure while maintaining the inflation red line; it seeks to restore bank liquidity without triggering asset bubbles. This sense of balance is key to understanding the market outlook.

Why is a slow and gradual easing more likely to lead to a structural market trend?

The market rally of the past few years was essentially due to "funds having no other choice": during interest rate hike cycles, low-risk assets yielded poor returns, and a large amount of existing funds could only circulate idly in risky assets such as stocks and cryptocurrencies, creating the strange phenomenon of "banks lacking funds but the stock market soaring".

However, after the December decision, this logic completely changed. The core closed loop is "gradual interest rate cuts → moderate liquidity → funds have choices → asset differentiation." Given that inflation is still above the target and there is no new round of QE, gradual easing is more likely to correspond to a structural market trend rather than a full-blown bull market.

The first step, slow interest rate cuts, dictates that "liquidity can only improve moderately, without a massive influx of new funds." Historical data directly verifies this: if it's a relief-style interest rate cut (such as in 2008 and 2020), a sharp short-term interest rate cut combined with unlimited quantitative easing would cause a surge in liquidity, leading to a general rise in all assets—there's too much money, no need to be selective; however, if it's a preventative, slow interest rate cut (such as in 1995 and this time), the rate cuts are small and the intervals are long, resulting in only a "marginal improvement" in liquidity. There's no massive influx of new funds; it can only rely on the reallocation of existing funds.

The second step is that funds have shifted from "blindly chasing rising prices" to "being selective." After the Federal Reserve restored bank liquidity, funds have new destinations: on the one hand, with ample reserves, banks are able to lend, and funds can enter the real economy (such as loans for businesses to expand production and consumer loans); on the other hand, gradual interest rate cuts have caused the yields on government bonds and high-grade corporate bonds to decline slowly, making these low-risk assets attractive again. Simply put, in the past, funds "had no choice" and could only crowd into risky assets; in the future, funds "have choices" and will naturally no longer blindly chase all assets.

The third step in this differentiation is that "only certainty will attract capital." Given the Federal Reserve's slight upward revision of its 2026 real GDP growth forecast to slightly above 2%, indicating an increased probability of a soft landing, assets more likely to attract capital in the future fall into two categories: First, those with strong fundamentals, such as AI and semiconductors with clear industry narratives and profit growth, high-quality consumer stocks with stable cash flow, and a few high-dividend sectors and some REITs benefiting from declining interest rates and soft landing expectations. Second, low-risk assets, such as high-grade corporate bonds and short-term government bonds. Meanwhile, those low-quality stocks and small-cap cryptocurrencies lacking fundamental support and relying solely on liquidity speculation are more likely to experience valuation squeeze and a cooling of trading activity, lacking both new capital inflows and fundamental support.

Here's a simple analogy: In the past, the market was like a "big pot of food," where as long as there was liquidity, all assets could get a share; in the future, the market will be like a "buffet," where funds will only pick what they think is "reliable," and those lacking in nutritional value will gradually be neglected.

Two key variables: They don't change the overall direction, only affect the pace.

Many people worry that the "approximately 50bp cut over the next two years" and the "change of Federal Reserve Chair" might alter the overall direction of the structural market trend. However, considering the policy logic and economic background, these two variables will only affect the market rhythm, not shake the core trend.

First, consider the "approximately 50 basis point cuts over the next two years": This is a "mild positive" for the market, but not a "broad-based rally trigger." The gradually decreasing cost of capital will provide some support for the valuations of tech and growth stocks—after all, these assets are more sensitive to the cost of capital. However, 25 basis points at a time is too small. Historically, a full-blown bull market requires at least a cumulative interest rate cut of 100 basis points, coupled with quantitative easing (QE). Therefore, this pace will only make the structural market more stable, not trigger a frenzy.

Let's look at the "Federal Reserve Chair transition": Under the current term arrangement, Powell's term as chair will expire in May 2026, at which point he will face the choice of either reappointment or re-election. Short-term fluctuations are possible, but as long as inflation has fallen but remains slightly above 2% and the economy continues its soft landing path, long-term policy will not shift. Regardless of their inclinations, current candidates support interest rate cuts; the disagreement lies only in the "pace" rather than the "direction." The constraints on direction come from three hard conditions: the inflation target, debt levels, and financial stability considerations, which will not fundamentally change due to a change in leadership. Even if a more radical candidate is elected, it will be difficult to implement massive stimulus—on the one hand, the Fed has a tradition of policy continuity; on the other hand, the current US core PCE is still above the 2% target, and aggressive rate cuts would trigger an inflation rebound; more importantly, the US government debt ratio has exceeded 120%, and significant easing would exacerbate debt risks. Therefore, the transition may cause short-term market volatility in 2026, but it will not change the overall direction of "slow easing and structural measures."

Some may ask, "If the economy suddenly enters a recession, will it be forced to aggressively cut interest rates?" MSX Research believes that, based on current data, the baseline scenario remains a soft landing. A significant recession is not currently the mainstream expectation, but it is still a tail risk that needs to be hedged. The Federal Reserve has just slightly raised its 2026 real GDP growth forecast to slightly above 2%, and although the unemployment rate has risen from its previous low, it remains at a historically low level, increasing the probability of a soft landing. Even if a slight recession occurs, considering the stickiness of inflation, the Federal Reserve will most likely cut interest rates "small and in stages," and will not repeat the mistakes of 2020.

In conclusion, the key to the future is "finding certainty," not "finding funding."

The real significance of the Fed's December decision is that it has clearly defined the boundaries for the market over the next 1-2 years: there will be no shortage of money, but there will also be no unlimited money; there will be no more continuous tightening, but there will also be no massive stimulus. The era of "money circulating aimlessly and driving up all assets" is over. The future market will not be tested on "whether it can find funds," but on "whether it can find certainty that makes funds feel secure."

For investors, instead of worrying about "when will the next interest rate cut come?" or "will the new chairman be more accommodative?", it's better to focus on the core logic: Which sectors offer clear industry dividends? Which assets have stable profit support? Which assets can truly absorb the funds flowing from the financial market to the real economy? Specifically, these certainties can be broken down into three categories: certain industry trends (AI, digitalization, energy transition, etc.); certain profits and dividends (leading companies with high cash flow visibility); and certain beneficiaries of interest rate paths (high-grade bonds, medium-term interest rate products). These sectors with certainty are the core winners in the future structural market trend.

Ultimately, the Fed's decision has served as a "risk education" lesson for the market: the frenzy fueled by liquidity speculation will eventually end, and only genuine value growth can weather economic cycles. This is the new market rule in the era of slow easing.