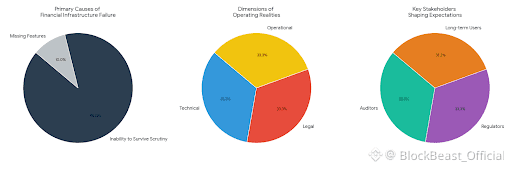

When looking at a project like Walrus through the lens of someone accustomed to regulated financial infrastructure, the first thing that stands out is not novelty but posture. The protocol does not appear to be designed to impress quickly or to collapse multiple ambitions into a single, sweeping promise. Instead, it reflects a cautious attempt to reconcile decentralized systems with the realities of operating under scrutiny—technical, legal, and operational. That posture matters more than it might seem. Most failures in financial infrastructure are not caused by missing features, but by an inability to survive contact with auditors, regulators, or long-term users whose expectations are shaped by boring but unforgiving standards.

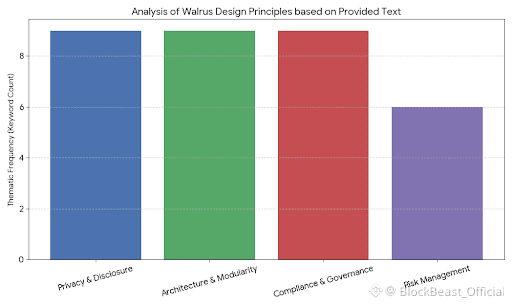

Walrus’ emphasis on privacy is a useful place to start, precisely because it avoids absolutism. In regulated environments, privacy is never binary. Institutions do not ask whether data is hidden or revealed; they ask under what conditions, to whom, and with what evidentiary guarantees. The design choice to support private transactions while still enabling governance participation, staking, and interaction with dApps suggests an understanding of privacy as conditional and contextual. Selective disclosure, the ability to produce records when required, and the preservation of audit trails are not concessions to regulation—they are prerequisites for any system that expects to be used beyond a narrow, ideologically aligned user base. Absolute opacity tends to collapse under its own weight once real money, real users, and real liabilities are involved.

The decision to build on Sui, and to leverage erasure coding and blob storage for decentralized data distribution, also reads as an attempt to address operational constraints rather than chase architectural purity. Separating concerns—storage from execution, data availability from transaction logic—reduces systemic risk. It limits the blast radius of failures and makes it easier to reason about performance, costs, and upgrade paths. From a compliance perspective, this modularity is not an abstract virtue. It allows components to be assessed, audited, and potentially isolated if regulatory requirements change. Systems that entangle everything into a single layer often discover too late that they have also entangled their risk.

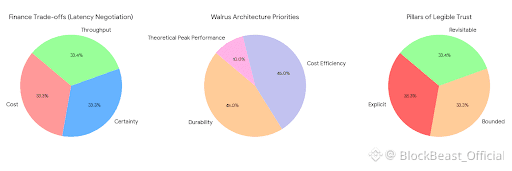

There is also a notable lack of insistence on immediacy. Settlement latency, particularly when large files or complex transactions are involved, is treated as a constraint to be managed rather than a flaw to be denied. In traditional finance, latency is negotiated constantly—between cost, certainty, and throughput. Real systems accept that faster is not always better if it undermines predictability or increases operational fragility. Walrus’ architecture appears to accept similar trade-offs, favoring durability and cost efficiency over theoretical peak performance. This is not glamorous, but it is recognizable to anyone who has had to explain system behavior to risk committees or regulators.

Bridges and migrations, especially in a multi-chain environment, introduce trust assumptions that cannot be hand-waved away. A protocol that acknowledges these assumptions implicitly—by limiting their scope and by avoiding unnecessary complexity—signals a more mature understanding of how failures actually propagate. No bridge is trustless in the way marketing materials often imply. What matters is whether the trust is explicit, bounded, and revisitable. Conservative engineering, in this sense, is less about eliminating risk than about making it legible.

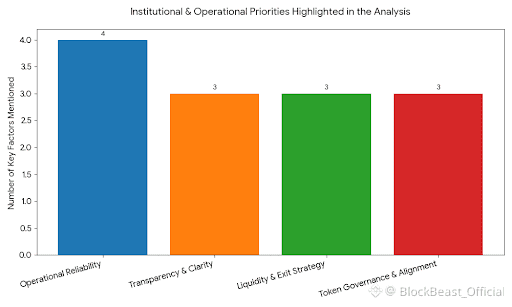

Operational details often reveal more about intent than whitepapers do. Node upgrade processes, documentation clarity, and tooling maturity are not secondary concerns when systems move from experimentation to production. Financial institutions do not tolerate ambiguity in upgrade schedules or unclear failure modes. If a protocol cannot explain how it changes over time, it will not be allowed to hold meaningful value. Walrus’ focus on predictable infrastructure behavior and developer compatibility suggests an awareness that longevity is earned through repetition and reliability, not through constant reinvention.

Token design, viewed from an institutional standpoint, is rarely about upside narratives. Liquidity, exit flexibility, and the ability to unwind positions without distorting markets matter far more than incentive diagrams. A token that primarily functions as a coordination and access mechanism—governance participation, staking alignment, and usage within the protocol—fits more comfortably into existing compliance frameworks than one framed as an abstract claim on future growth. Institutions need to know not just how to enter a position, but how to leave it without triggering legal, accounting, or reputational issues. Designs that acknowledge this reality tend to age better.

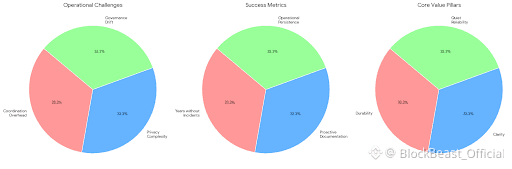

None of this implies that Walrus is without limitations. Distributed storage at scale introduces coordination overhead. Privacy mechanisms increase complexity and can complicate user experience. Governance systems can drift or stagnate. These are not weaknesses unique to this project; they are the cost of operating in the real world rather than in theoretical models. What matters is whether these constraints are surfaced honestly and managed deliberately.

In that sense, Walrus resembles infrastructure built with the expectation of being examined closely and used for longer than a market cycle. It does not promise to transform finance or replace existing systems overnight. Instead, it seems oriented toward coexistence—providing decentralized, privacy-aware tooling that can survive audits, regulatory questions, and the slow erosion that follows operational neglect. In regulated environments, success is rarely loud. It is measured in years without incidents, in documentation that answers questions before they are asked, and in systems that continue to function after enthusiasm has moved elsewhere. Durability, clarity, and quiet reliability are not inspiring metrics, but they are the ones that endure.