One of the biggest bottlenecks in decentralized systems isn’t innovation.

It’s fear.

Teams hesitate to try new incentive models, economic parameters, or structural changes because mistakes are expensive and often irreversible. A bad experiment can corrupt data, confuse users, or permanently distort outcomes. As a result, many protocols evolve cautiously—or not at all.

Walrus quietly changes that by giving builders a place to experiment with consequences without polluting reality.

Experiments Usually Fail for the Wrong Reasons

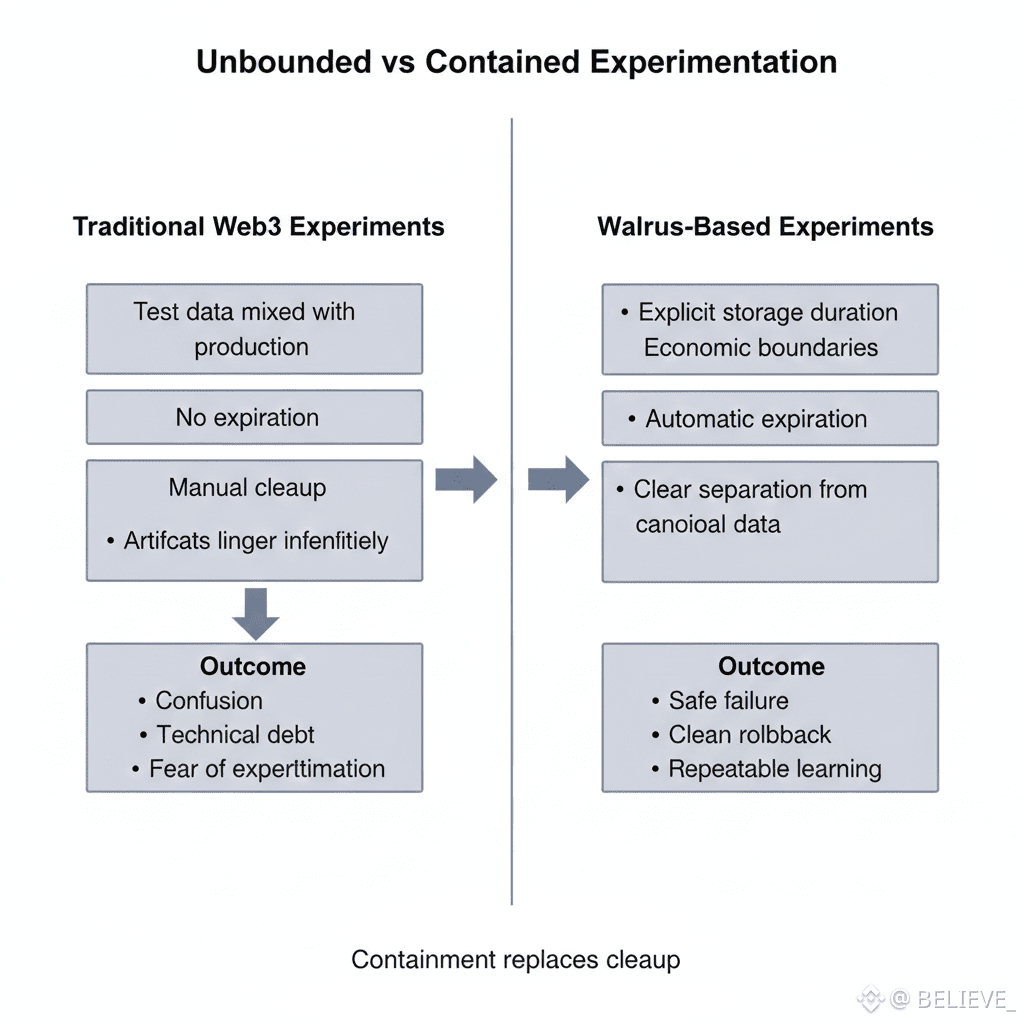

When experiments go wrong in Web3, it’s rarely because the idea was flawed. It’s because the environment was uncontrolled.

Data mixes with production state. Temporary artifacts linger forever. Test outputs get mistaken for canonical records. Cleanup is manual and often incomplete.

Walrus introduces a discipline that most experimentation lacks: explicit boundaries.

When data is stored with a defined duration and economic scope, experiments can be isolated by design. Outputs exist only as long as they’re funded. When the test ends, the artifacts naturally disappear unless someone deliberately keeps them alive.

That’s not deletion.

That’s containment.

---

Sandboxes That Behave Like the Real System

A common problem with test environments is that they don’t behave like production. Incentives are fake. Costs are abstract. Failures don’t matter.

Walrus eliminates that gap.

Experiments conducted on Walrus use the same mechanics as production: real availability guarantees, real funding decisions, real expiration. The difference isn’t realism—it’s intent. Everyone involved knows the data is provisional.

This creates a rare middle ground between simulation and deployment. Teams can test ideas under realistic conditions without committing to permanence.

Economic Experiments Without Long-Term Fallout

Many protocol changes are economic in nature: fee structures, reward curves, access thresholds, storage strategies. Testing these safely is hard because economic artifacts tend to stick around.

Walrus lets economic experiments leave footprints that fade.

A DAO can test a new incentive model by publishing datasets, metrics, or outputs that support the experiment. Participants can inspect results. Analysts can evaluate behavior. But when the trial ends, the data doesn’t haunt future decisions unless it’s intentionally preserved.

History becomes optional, not compulsory.

WAL Enforces Seriousness Without Lock-In

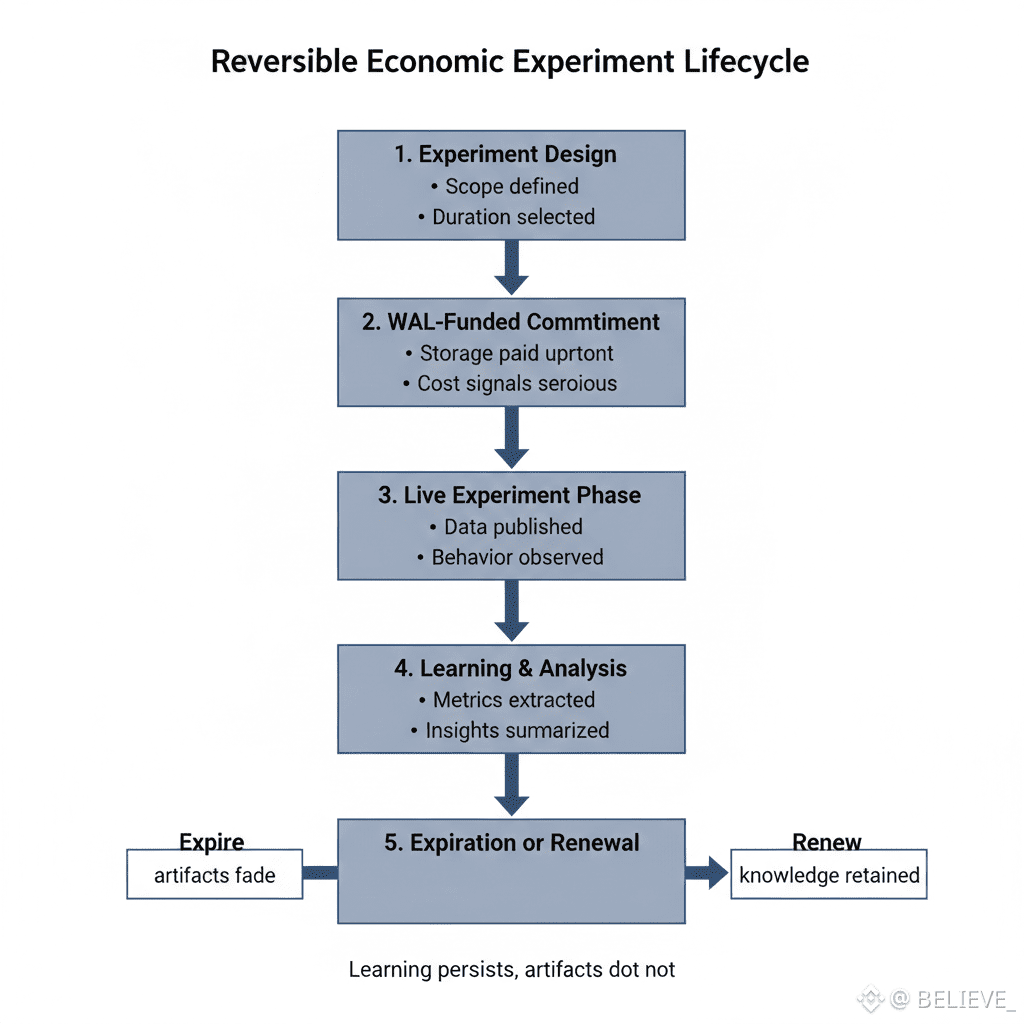

The presence of WAL introduces an important constraint: experiments aren’t free.

This is a feature, not a flaw.

Because storing experimental data costs something, teams are forced to scope experiments thoughtfully. You don’t archive every log forever. You choose what matters. You fund what you intend to analyze.

That cost filters noise. It discourages sloppy experimentation while still allowing meaningful trials. Crucially, it avoids the opposite problem: experiments that are “cheap” enough to ignore consequences.

Walrus creates experiments that people care about—without trapping them afterward.

Learning Without Accumulating Debt

One of the quiet failures of innovation is accumulation. Old experiments clutter systems. Forgotten trials confuse newcomers. Nobody knows which artifacts are canonical.

Walrus prevents this by making expiration the default outcome.

Unless someone decides a result is worth keeping, it fades. The system doesn’t accumulate evidence accidentally. It only retains what someone values enough to support.

This keeps learning lightweight. Insights can be summarized, conclusions extracted, and raw data allowed to expire without guilt.

The system learns, but it doesn’t hoard.

Safer Social Experiments

Not all experiments are technical.

Communities test coordination mechanisms, participation incentives, and contribution models. These social experiments often produce sensitive or controversial data.

Walrus allows these trials to be bounded in time. Data can be preserved long enough for reflection, then allowed to expire to avoid permanent reputational harm or misinterpretation.

This lowers the social risk of experimentation. Communities become more willing to try new structures when failure doesn’t leave permanent scars.

---

Reversible Exploration Encourages Bolder Design

The ability to walk away from an experiment matters.

When teams know that experimental artifacts won’t permanently define them, they take bigger risks. They explore ideas that might not survive long-term scrutiny but are worth testing.

Walrus doesn’t make systems reckless.

It makes them brave without being careless.

The cost of being wrong becomes manageable. The cost of never trying becomes obvious.

---

Why This Matters Long-Term

Decentralized systems often stagnate because they conflate experimentation with commitment. Every change feels final. Every dataset feels permanent.

Walrus separates the two.

It allows systems to explore widely while committing narrowly. Over time, this produces better outcomes—not because teams are smarter, but because they can afford to learn.

Innovation thrives where mistakes are survivable.

Final Thought

Progress requires experimentation.

Experimentation requires safety.

Safety requires boundaries.

Walrus provides those boundaries—not by locking systems down, but by letting experiments exist without demanding forever.

In a space obsessed with permanence,

Walrus reminds us that learning is temporary,

and that’s exactly what makes it powerful.