@Walrus 🦭/acc When people talk about NFTs, they usually talk about the picture. The art, the community, the trading. But if you live close to the wiring, you start noticing a quieter question hiding underneath: where does the actual material live, and what happens to it when the mood changes? Walrus sits inside that question. Not as a brand story, but as a place where data is treated like something you might one day have to defend—under pressure, under scrutiny, or simply under the slow grind of time.

Walrus makes more sense if you stop thinking of storage as a neutral bucket and start thinking of it as a promise. A promise that an NFT’s media, an AI dataset, or a game archive will still be reachable when a server disappears, when a contract dispute happens, or when a team changes hands. At mainnet, Walrus described itself as a decentralized storage network built to change how applications engage with data, including the ability for data owners to keep control and even delete what they stored. That last part matters more than people realize. Ownership without the ability to reverse a mistake is just a different kind of trap, and a lot of creators have already learned that lesson the hard way.

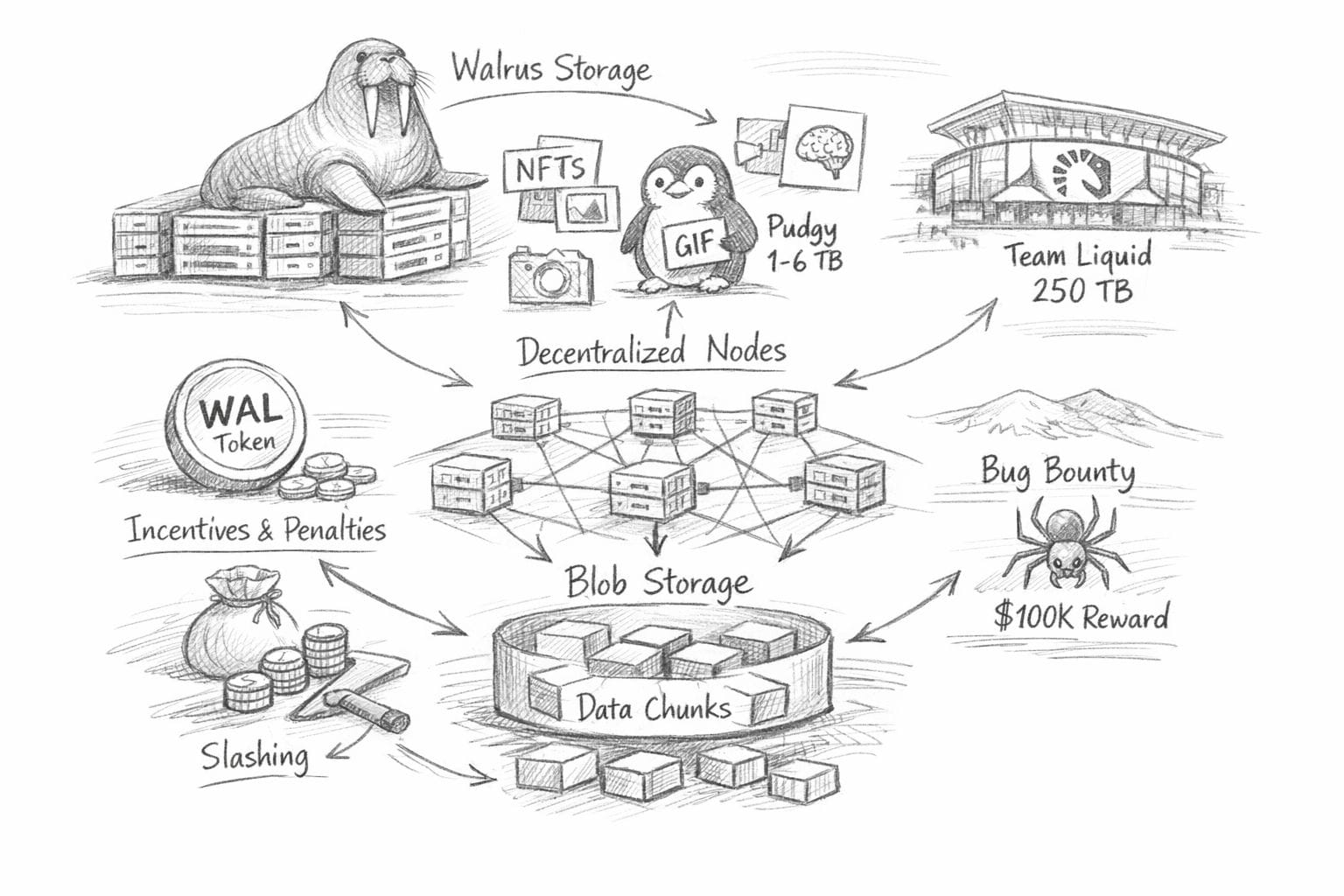

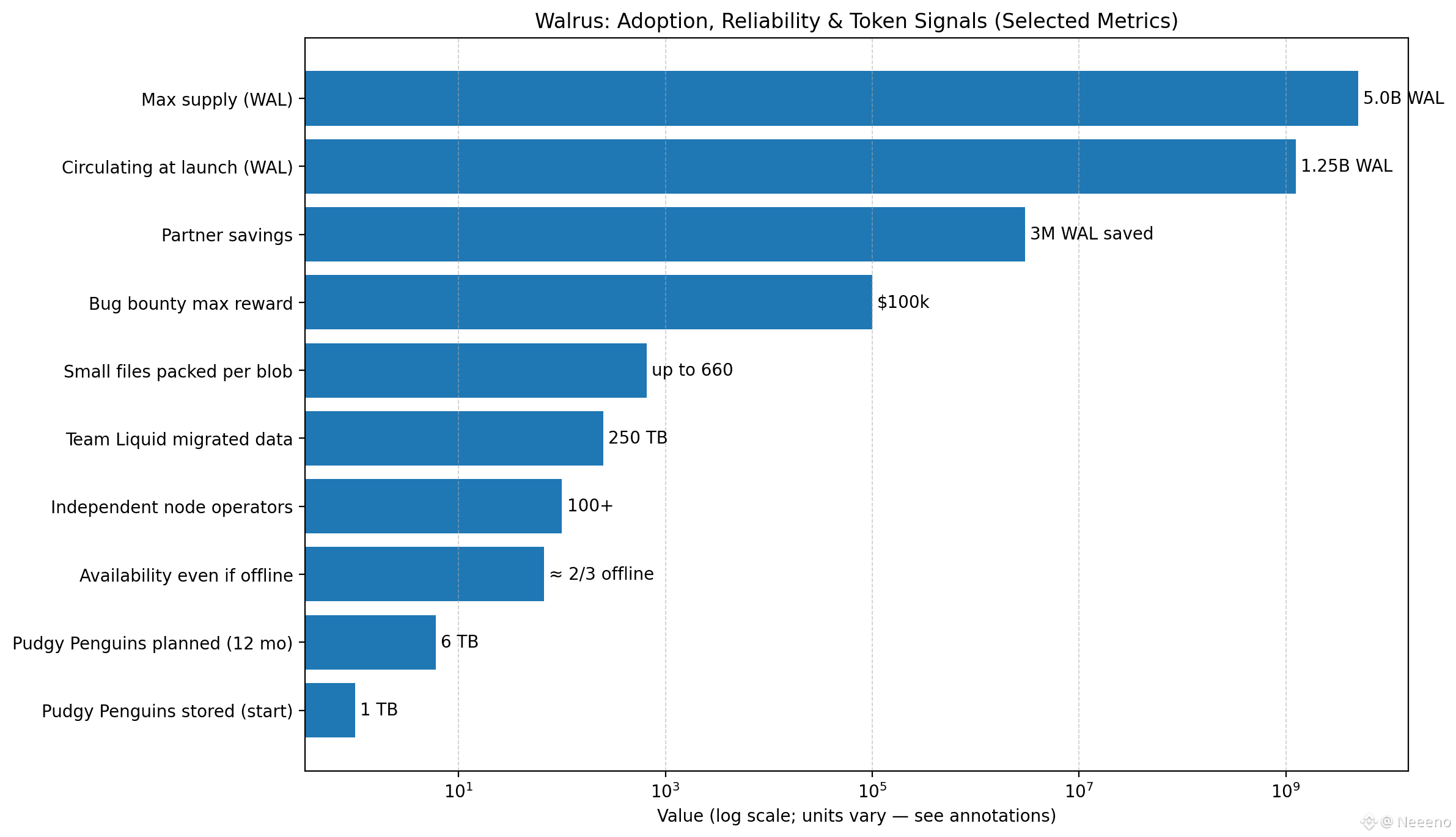

The real emotional burden in Web3 isn’t novelty; it’s permanence. Creators want permanence when it protects them, and flexibility when it scares them. Walrus tries to hold both without pretending the tension isn’t real. It’s why “efficient blob storage” isn’t only about cost. It’s about reducing the background fear that your work is one outage away from becoming a broken link, or one vendor decision away from becoming inaccessible. Walrus has emphasized that its network runs through over 100 independent node operators, and that the storage model is designed so data stays available even if up to two-thirds of nodes go offline. You can feel the difference between a system that assumes calm conditions and one that keeps asking, “What if things go wrong?”

NFTs are where this becomes personal fast. A collector doesn’t just buy an image; they buy a belief that the image will remain the same image tomorrow. The moment provenance feels shaky, the market turns anxious, and anxiety always finds a technical weakness to blame.

Walrus is starting to handle real media work, not just ideas on paper. In April 2025, Pudgy Penguins connected Walrus to store and manage files like stickers and GIFs. They began with 1TB and plan to grow to 6TB over the next year.

Those numbers are small compared to enterprise archives, but psychologically they’re big: they represent a brand choosing to move its daily creative operations onto infrastructure that can be verified, not just trusted

And then you see the scale jump, and it stops being a “crypto thing.” In January 2026, Team Liquid migrated 250TB of match footage and brand content to Walrus, described as the largest single dataset entrusted to the protocol so far. � That’s not a marketing milestone; it’s an operational one. It’s the kind of decision people make after living through broken drives, messy permissions, internal silos, and the dull panic of losing something you can’t recreate. Walrus frames that move as eliminating single points of failure and turning archives into onchain-compatible assets without needing to migrate again as use cases evolve. In plain terms: fewer future emergencies.

AI provenance is where Walrus starts to feel almost inevitable, because AI exposes how fragile our data culture really is. Walrus recently put the problem bluntly: bad data derails AI projects, and it spills outward into industries that depend on records they can’t verify. The piece cites a claim that 87% of AI projects fail before reaching production due to data quality problems, and it points to examples like bias in training data forcing major efforts to be scrapped. Whether you’re building an AI model or auditing one, the human issue is the same: when the decision matters, “trust me” is not a proof. Walrus’s stance is that data should come with a trail you can show to other people, not just a story you tell yourself.

That’s why “provenance” on Walrus isn’t framed as a nice-to-have. It’s framed as a way to reduce conflict. When teams disagree about what dataset was used, which file version is “the real one,” or whether a record was altered after the fact, those disagreements don’t stay technical. They become legal, financial, and reputational. Walrus talks about files having verifiable identifiers and histories you can point to, which becomes especially important when regulators—or business partners—ask why an automated system made a choice. If you’ve ever been in the room when blame starts bouncing between teams, you understand why this matters: verifiability isn’t just security; it’s emotional safety for organizations that can’t afford ambiguity.

But systems don’t stay honest because the whitepaper says so. They stay honest because the incentives punish laziness and reward care, especially when nobody is watching. Walrus is explicit that its storage economy is powered by the WAL token and built around rewards and penalties for reliability. WAL is also designed with a specific shape: a max supply of 5,000,000,000 and an initial circulating supply of 1,250,000,000 at launch, with 43% allocated to a community reserve, 10% to user distribution, 10% to subsidies, 30% to core contributors, and 7% to investors. Even the release schedule tells a story about time horizons: the community reserve includes 690M available at launch with a linear unlock until March 2033, and the investor portion unlocks 12 months from mainnet launch.That’s a long way of saying Walrus is trying to make “staying” more rational than “grabbing.”

The economics become most interesting when you look at the parts that feel slightly annoying—because those are usually the parts that stop the system from getting gamed. Walrus describes penalties on short-term stake shifts, partly burned and partly distributed to long-term stakers, because sudden stake movements force expensive data migration across storage nodes.It also describes slashing for low-performing nodes once enabled, with a portion burned, to push stakers toward operators who actually do the work.These aren’t glamorous mechanisms. They’re the protocol admitting that people will try to optimize for themselves, and that the network has to turn “doing the right thing” into the least painful path.

In 2025, Walrus also leaned into practicality: improving the way small files are handled and reducing overhead for teams that don’t want to babysit storage workflows. In its year-in-review, Walrus said it shipped a native approach that groups up to 660 small files into a single unit, saving partners more than 3 million WAL, and it also introduced a smoother upload path so client apps don’t have to manage distributing data across hundreds of nodes—especially helpful for mobile connections that aren’t perfect. Those details sound mundane until you’ve watched a project fail because the last mile was too fragile. Reliability is often just “the boring part that didn’t break.

And because security is not a claim—it’s a posture—Walrus put money behind scrutiny. Its bug bounty program offers rewards up to $100,000 for vulnerabilities that could impact security, reliability, or economic integrity, with clear examples around data deletion, bypassing payments, or compromising availability proofs.That’s a signal to builders and institutions that Walrus expects real adversarial pressure, not just friendly testing. If you’re storing irreplaceable media or sensitive AI training data, you want a protocol that assumes it will be attacked, not one that hopes it won’t.

WAL’s role in all this is not abstract. It’s how Walrus turns storage from a one-time action into an ongoing service that has to be paid for across time. Walrus describes storage fees paid upfront and then distributed over time to operators and stakers as compensation for keeping data safe, alongside subsidies intended to lower early user costs while keeping operators economically viable.That matters because storage isn’t like a transaction that happens and disappears. Storage is a responsibility that keeps accumulating, epoch after epoch, even when nobody is paying attention anymore.

You can feel Walrus’s worldview most clearly in the way it talks about decentralization as a moving target, not a box you check.

.

In January 2026, it argued that a network stays decentralized only if it’s designed to stay that way. It described rules that encourage spreading stake across many participants, pay more to those who perform well, discourage fast “in-and-out” stake moves, and let the community steer major settings together. The point is straightforward: once control gathers in a small group, censorship and instability can quietly return. If creators and users are meant to be safe here, that safety has to hold up when the stakes get higher.

The title you gave—NFTs, AI provenance, and Web3, powered by efficient blob storage—sounds like three worlds. Walrus treats them like one world with one shared weakness: we keep building value on top of data we can’t reliably verify, control, or preserve. When things are calm, that weakness feels theoretical. When markets get volatile, when partnerships break, when regulators ask questions, or when an archive matters years later, it becomes painfully real. Walrus is trying to be the kind of infrastructure that doesn’t ask for attention. It asks for responsibility: a network of operators who can’t hide bad performance, a token economy that rewards patience over opportunism, and a data layer designed for the day you most need it, not the day you’re most excited.

Quiet infrastructure is rarely celebrated, and honestly it shouldn’t be. If Walrus does its job well, most users will never think about it. They’ll just notice that the NFT still resolves, the dataset still matches what was promised, the archive is still there, and the story can still be proven when someone challenges it. That’s not glamour. That’s reliability. And in a world where attention comes cheap and trust does not, reliability is the most respectful thing a system can offer.