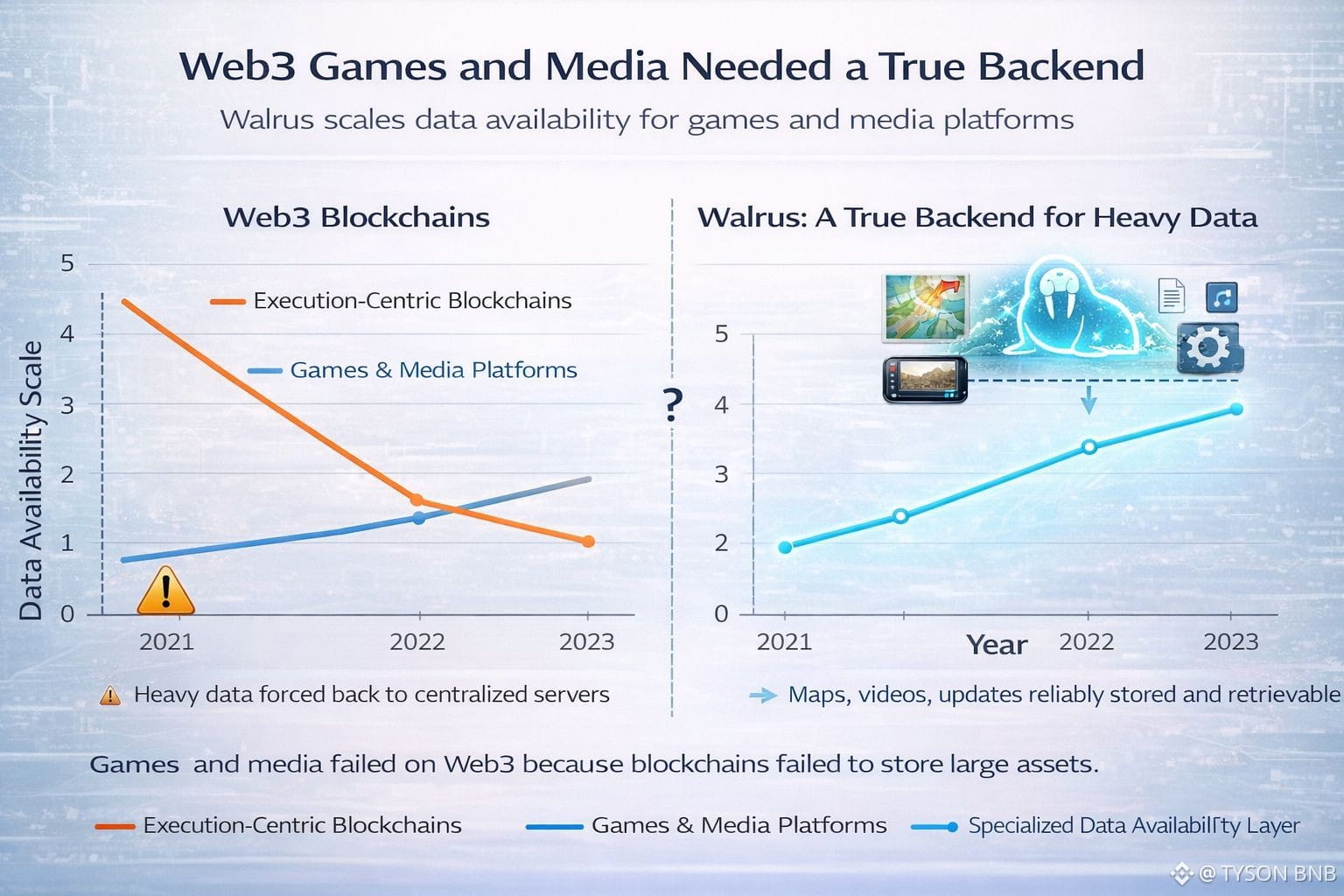

Web3 games and media platforms didn’t struggle because of creativity, funding, or ambition. They struggled because blockchains were never designed to carry the weight of what these experiences actually produce. High-resolution assets, constantly updated game states, user-generated content, cinematic files, live media libraries all of this data was too big, too dynamic, and too persistent for execution-centric chains. So developers improvised. Centralized servers crept back in. “Hybrid” architectures became normal. Decentralization stopped at the UI. Walrus enters this story not as another storage option, but as a structural correction: a backend that finally treats data as the main character, not an inconvenience.

Web3 games and media platforms didn’t struggle because of creativity, funding, or ambition. They struggled because blockchains were never designed to carry the weight of what these experiences actually produce. High-resolution assets, constantly updated game states, user-generated content, cinematic files, live media libraries all of this data was too big, too dynamic, and too persistent for execution-centric chains. So developers improvised. Centralized servers crept back in. “Hybrid” architectures became normal. Decentralization stopped at the UI. Walrus enters this story not as another storage option, but as a structural correction: a backend that finally treats data as the main character, not an inconvenience.

The core tension in Web3 gaming and media has always been this: execution wants to be fast and minimal, while content wants to be rich and long-lived. Games are not just transactions; they are worlds. Media platforms are not just ownership ledgers; they are archives of culture. Traditional blockchains compress everything into small, deterministic state updates, which works beautifully for finance and terribly for experiences. Walrus breaks this deadlock by separating data availability from execution entirely. It does not ask the chain to understand or execute game logic. It asks something simpler and more important: can this data be stored, verified, and retrieved reliably, without trusting a centralized host?

For game developers, this changes the architecture from the ground up. Instead of pushing assets into IPFS with fragile pinning assumptions or falling back to Web2 CDNs, Walrus offers a network explicitly designed for large binary objects. Game textures, maps, audio, replays, and patches can live in a decentralized environment that does not collapse under scale. The blockchain handles ownership, logic, and state transitions elsewhere, while Walrus ensures the world itself remains accessible. The game stops being half-decentralized by necessity and becomes fully modular by design.

Media platforms face a similar but even more acute problem. Video, music, and interactive media are not static files; they are living libraries that grow over time. Centralized platforms control not just distribution, but permanence. Content can be demonetized, removed, or silently altered. Walrus redefines this relationship by anchoring media availability in a decentralized layer that does not care about popularity, policy shifts, or platform incentives. Once data is stored, its availability is guaranteed by cryptographic commitments and economic incentives, not corporate discretion.

What makes Walrus very suitable for these scenarios is that it does not require every participant to store all the data. The network achieves durability, not by replicating universally, but through erasure coding and distributed responsibility. This is really important in the context of games and media, which are typically huge in terms of data volume. A system that calls for all nodes to store all data is definitely not scalable. Walrus understands this and thus, it allows specialization without sacrificing trust.

Moreover, the architects have been granted a great deal of liberty thanks to their choice of design. Knowing that the assets will not depend on a single platform for their existence, developers can craft creations which survive studios, publishers, or even the game client that was initially used. A character skin, a cinematic cutscene, or a user, generated map could each be a strong component in a shared ecosystem. Through mods, forks, and reinterpretations, artists can express their ideas more freely, as those practices have been made technically possible instead of being legally or infrastructurally prohibited. Walrus does not just store data; it preserves creative possibility.

Another overlooked advantage is versioning and history. Games and media evolve. Updates roll out. Assets change. In centralized systems, old versions disappear unless explicitly archived. Walrus allows historical data to remain accessible, enabling time-travel within digital worlds. Players can revisit old versions of a game environment. Media researchers can analyze how content evolved. This continuity aligns far better with how culture actually behaves layered, iterative, and persistent than the disposable logic of Web2 backends.

Performance issues become a major point of debate around decentralized storage, especially if it involves games or other types of highly interactive experiences. Walrus handles this challenge not by denying the importance of latency but by accommodating realistic access patterns in its design. For instance, games and media platforms perfectly combine caching, streaming, and prefetching and at the same time, consider Walrus as the ultimate data source. Moreover, the decentralized backend is not required to serve every byte to every user in real time; it only needs to make sure that the data is present and can be gotten when required. This difference, though subtle, is of great importance. It gives an opportunity for performance enhancements while at the same time retaining control.

More than that, on a financial level, Walrus makes the alignment of incentives much cleaner than turning to these kind ofwear solutions in a piecemeal fashion. Instead of playing the speculate or being rewarded for short, term usage spikes, storage providers get paid for the service of availability. This brings about a more stable cost structure for the developer, who can now think and prepare for the storage economics of a predictable nature rather than the volatile infrastructure bills shock. For media platforms, this stability is essential. Cultural archives cannot depend on quarterly revenue cycles or shifting platform priorities. They need infrastructure that is boring, reliable, and indifferent to trends.

There is a deeper philosophical implication here as well. Web3 games and media often talk about “ownership,” but ownership without persistence is hollow. If the asset exists only as long as a server is maintained, control is illusory. Walrus restores meaning to ownership by ensuring that the underlying data does not vanish when incentives change. Ownership becomes something more than a token pointer; it becomes a relationship to an object that actually exists in a resilient system.

From a system design perspective, Walrus encourages cleaner boundaries. Execution layers focus on logic and consensus. Application layers focus on experience. Walrus focuses on data. Each layer does what it is best at, and none are overloaded with responsibilities they were never meant to carry. The modularity of this is reminiscent of how effective software systems on a large scale are developed outside the crypto world. It represents a sign of growth rather than of division.

Ultimately, Walrus as a backend is less about decentralization as ideology and more about decentralization as ergonomics. It makes building rich, data-heavy experiences easier, not harder. It removes the constant tension between ambition and feasibility that has haunted Web3 games and media since their inception. Instead of asking developers to compromise on scale or permanence, Walrus gives them a place where the heavy parts of their vision can live.

In a space obsessed with execution speed and financial primitives, Walrus quietly solves the unglamorous problem that actually defines user experience: where does everything go, and will it still be there tomorrow? For Web3 games and media platforms trying to move beyond experiments and into lasting worlds, that question is not secondary. It is foundational.