When I first started exploring decentralized storage, one concern kept coming back to me: what happens to data over decades? In traditional systems, hardware fails, magnetic disks degrade, and even SSDs can silently lose bits. This “bit rot” isn’t a theoretical problem—it’s real, and when you are storing critical data, it can’t be ignored...

Walrus tackles this issue with a combination of design principles and practical mechanisms that are embedded into the protocol from day one. Unlike conventional cloud storage, which often assumes hardware reliability and periodic backups, Walrus treats every piece of data as fragile and ephemeral unless actively maintained.

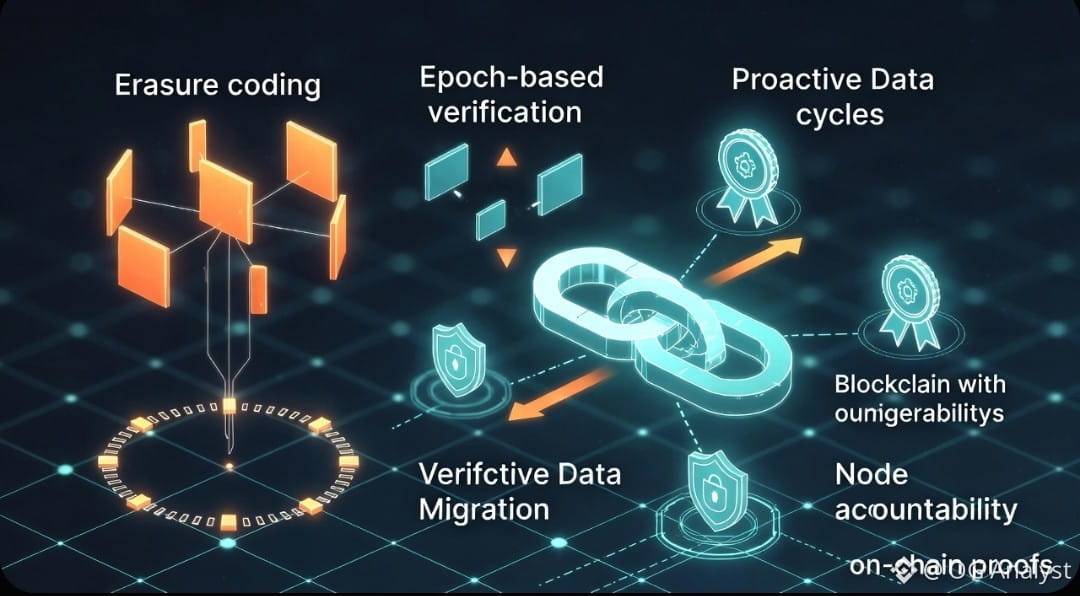

Redundancy Through Erasure Coding

At the core of Walrus’s approach is Red Stuff, an advanced erasure coding scheme. Unlike simple replication, erasure coding splits data into multiple slivers and encodes them across differently sized dimensions. Each sliver is stored on different nodes, providing resilience against node failures and bit-level degradation.

From my perspective, the beauty of this system is twofold:

1. It reduces storage overhead compared to full replication.

2. It allows efficient reconstruction if any part of the data becomes corrupted.

When a sliver starts to degrade, Walrus doesn’t wait for catastrophic failure. It actively reconstructs lost or corrupted parts using the remaining healthy slivers. This reconstruction is continuous and automatic, rather than reactive, meaning the network self-heals long before you notice a problem.

Epoch-Based Verification

Another key strategy is epoch-based verification. Walrus operates in defined epochs, during which nodes are challenged to prove availability and integrity of their stored slivers.

I find this approach particularly elegant because it creates a rhythm of ongoing verification rather than relying on occasional audits. Nodes submit proofs of availability, which act as cryptographic evidence that the data they store remains intact.

If a sliver fails to meet the proof requirements, the system flags it for repair. This ensures that bit rot is caught early, even in a highly decentralized environment where nodes may go offline temporarily or experience local hardware errors.

Proactive Data Migration

Dealing with long-term degradation isn’t just about repairing corrupted slivers—it’s also about staying ahead of technological decay. Hard drives, SSDs, and even future storage media have limited lifespans. Walrus incorporates proactive migration strategies, moving slivers from older or unreliable nodes to healthier ones.

From a practical standpoint, this is like maintaining a living archive: data isn’t just stored; it’s actively nurtured. The migration process is transparent to users, and the network handles it automatically, ensuring that long-term storage commitments remain viable.

Balancing Cost and Reliability

One question I often consider is how the system balances cost with redundancy. High levels of replication or frequent integrity checks can be expensive. Walrus addresses this by allowing configurable redundancy parameters.

For datasets that must last decades, you might choose higher redundancy and more frequent verification cycles. For less critical data, lower redundancy might suffice. WAL payments are tied to these choices, aligning economic incentives with the reliability guarantees users require.

Node Accountability

Maintaining data integrity over time isn’t just a technical problem—it’s a social one. Walrus incentivizes nodes to remain honest through staking and reward mechanisms. Nodes that fail to maintain slivers risk losing staked WAL or having their reputation diminished.

This accountability layer ensures that long-term degradation is not just a theoretical concern. Nodes have a real incentive to participate in self-healing and proactive maintenance, because their economic returns depend on it.

Integration With On-Chain Proofs

From my perspective, one of the most innovative aspects of Walrus is how it leverages the underlying blockchain—Sui—to anchor proofs of data integrity. Each reconstruction, verification, and availability proof is ultimately tied to an on-chain commitment.

This means that even if nodes change over time, the historical integrity of the data is cryptographically verifiable. Future auditors or applications can confidently assert that the stored data has never been silently corrupted or lost.

Human Reflection on Data Longevity

Thinking about data longevity makes me realize how fragile digital content can be without deliberate design. In my experience, most storage systems assume convenience over durability. Walrus flips that assumption. It treats each bit as an asset that requires care, and the combination of erasure coding, epoch verification, and proactive migration feels more like maintaining a living collection than storing files.

I also appreciate the transparency. As a user or developer, I know exactly what mechanisms protect my data, how often integrity is checked, and how economic incentives align with these protections. There are no hidden assumptions. Everything is deliberate and visible.

Conclusion

Walrus’s strategy for combating long-term data degradation is holistic. It combines redundant encoding, epoch-based verification, proactive migration, and node accountability to ensure that your data remains accessible and uncorrupted, even decades into the future.

By designing the system to detect and repair bit rot proactively, Walrus avoids the silent failures that plague conventional storage. And by tying these mechanisms to on-chain proofs and WAL incentives, it ensures that technical guarantees and economic realities are aligned.

For anyone who cares about the durability of digital assets—research data, compliance records, or critical application datasets—Walrus’s approach is thoughtful, practical, and, above all, trustworthy. It’s a system built not just to store data, but to preserve truth over time, in a way that reflects the realities of hardware, decentralization, and long-term stewardship.