When people talk about quantum encryption in blockchain circles, the discussion usually stays at a high level. It is framed as a future threat, something to worry about later when quantum computers become practical. For most projects, it sits in the category of “important, but not urgent” From the outside, that sounds reasonable. From an engineering point of view, it is often where problems quietly begin.

In long-lived systems, security failures rarely come from being unaware of a risk. They come from assuming that the risk can be handled with a clean upgrade when the time comes. Anyone who has worked on infrastructure that runs for years knows how unrealistic that assumption is. By the time a system is widely used, its cryptography is no longer a single component. It is woven into identity, transaction validation, key management, governance, and operational processes. Changing it is not a switch. It is a coordinated evolution.

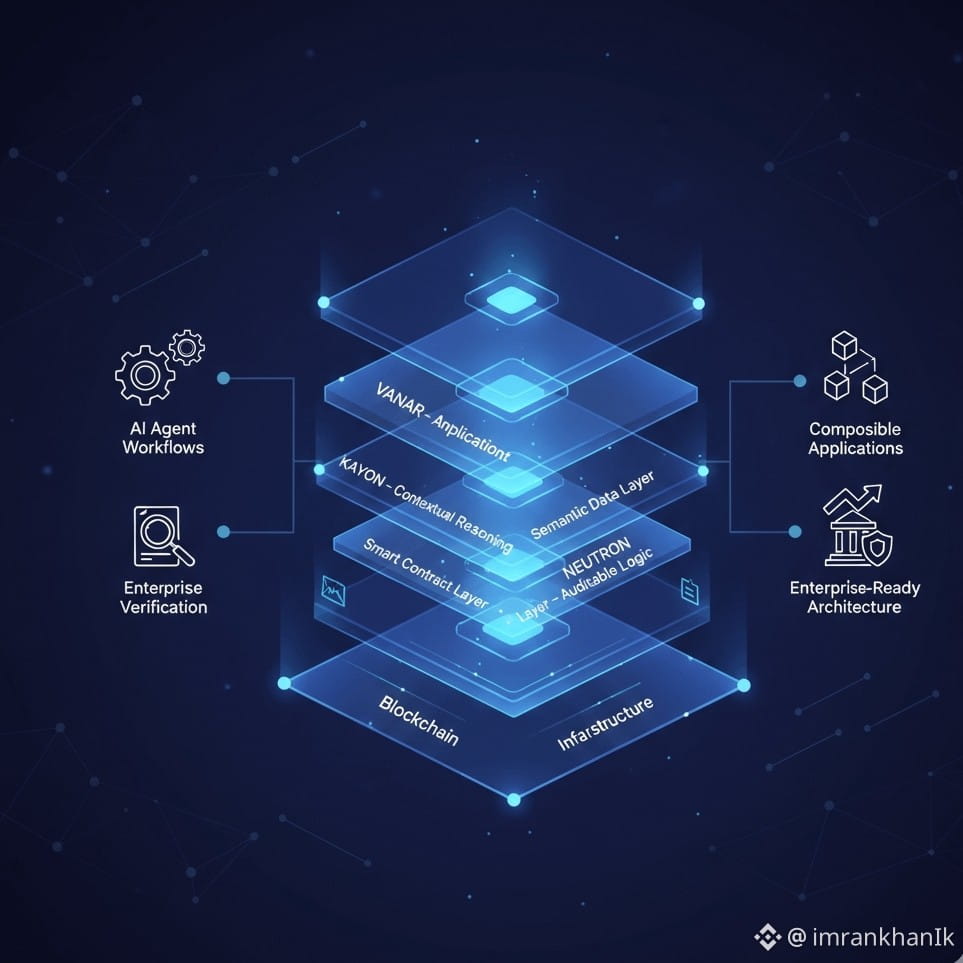

This is why the post-quantum question matters for Vanar and VANRY even before quantum computers are practical. The real issue is not whether a specific algorithm is quantum-resistant. It is whether the underlying infrastructure can adapt to new security assumptions without breaking trust or stability. That is a systems problem, not a cryptographic one.

In practice, blockchains operate under constant partial failure. Nodes upgrade at different times. Applications depend on specific behaviors. External integrations assume certain guarantees. During any major change, mixed environments are unavoidable. A network that cannot tolerate this reality becomes fragile. Many early blockchain designs did not prioritize this kind of adaptability because they were optimized for a narrower use case.

From a systems engineering perspective, early architectural decisions tend to compound. Choices about how keys are generated, how identities are represented, and how consensus enforces rules become deeply embedded over time. Retrofitting new security models later often means adding layers on top of old assumptions. Each layer solves a problem, but the overall system becomes harder to reason about and more difficult to maintain.

What stands out in Vanar’s approach is the emphasis on long-term operation rather than short-term demonstration. Instead of assuming that today's cryptographic standards will last indefinitely, the architecture leans toward modularity and predictable behavior. That does not remove future complexity, but it creates space to manage it. In systems terms, it lowers the cost of change.

Designing with post-quantum considerations in mind does not mean deploying cutting-edge cryptography prematurely. In fact, doing so can introduce its own risks. The more practical goal is cryptographic agility. That means building clear boundaries where algorithms can be updated, keys can be rotated, and rules can evolve without forcing a full redesign of the network. For VANRY, which is intended to support long-term application and data flows, this kind of stability matters more than headline performance.

There are real tradeoffs involved. Architectures that prioritize durability and upgrade paths often move more deliberately. They may appear less aggressive in the short term. But experience with large systems suggests that this restraint often pays off. When external conditions change, whether due to new security threats or regulatory shifts, systems designed for longevity tend to adapt with less disruption.

Retrofitted systems face a different challenge. Adding quantum-resistant mechanisms later can increase computational overhead, expand key sizes, and introduce new coordination problems. If a network was already operating near its limits, these changes can expose weaknesses that were previously hidden. This does not mean retrofitting cannot work, but it tends to be costly and operationally risky.

By contrast, platforms like Vanar that treat security as an evolving process are better positioned to absorb these shifts. Clear governance mechanisms, predictable upgrade processes, and conservative assumptions about long-term operation all contribute to resilience. These qualities are rarely exciting, but they are what keep systems functioning years after initial deployment.

Market narratives often lag behind this reality. Short-term performance and new features are easy to market. Quiet resilience is harder to quantify. Yet, when infrastructure underpins real economic and data activity, reliability matters more than novelty.

In the context of the post-quantum era, the central question for Vanar and VANRY is not when quantum computers arrive. It is whether the system can change its security foundations without eroding trust. Systems that can do that tend to last. Those that cannot are often remembered as technically impressive, but operationally fragile.