Permanent data sounds like safety until you realize permanence is also a liability.

Permanent data sounds like safety until you realize permanence is also a liability.

In Web3, permanence is marketed as a feature. “Stored forever.” “Immutable.” “Censorship-resistant.” The idea is seductive: if data can’t be erased, it can’t be lost, manipulated, or rewritten.

But permanence doesn’t just preserve truth.

It preserves mistakes, obligations, and risk.

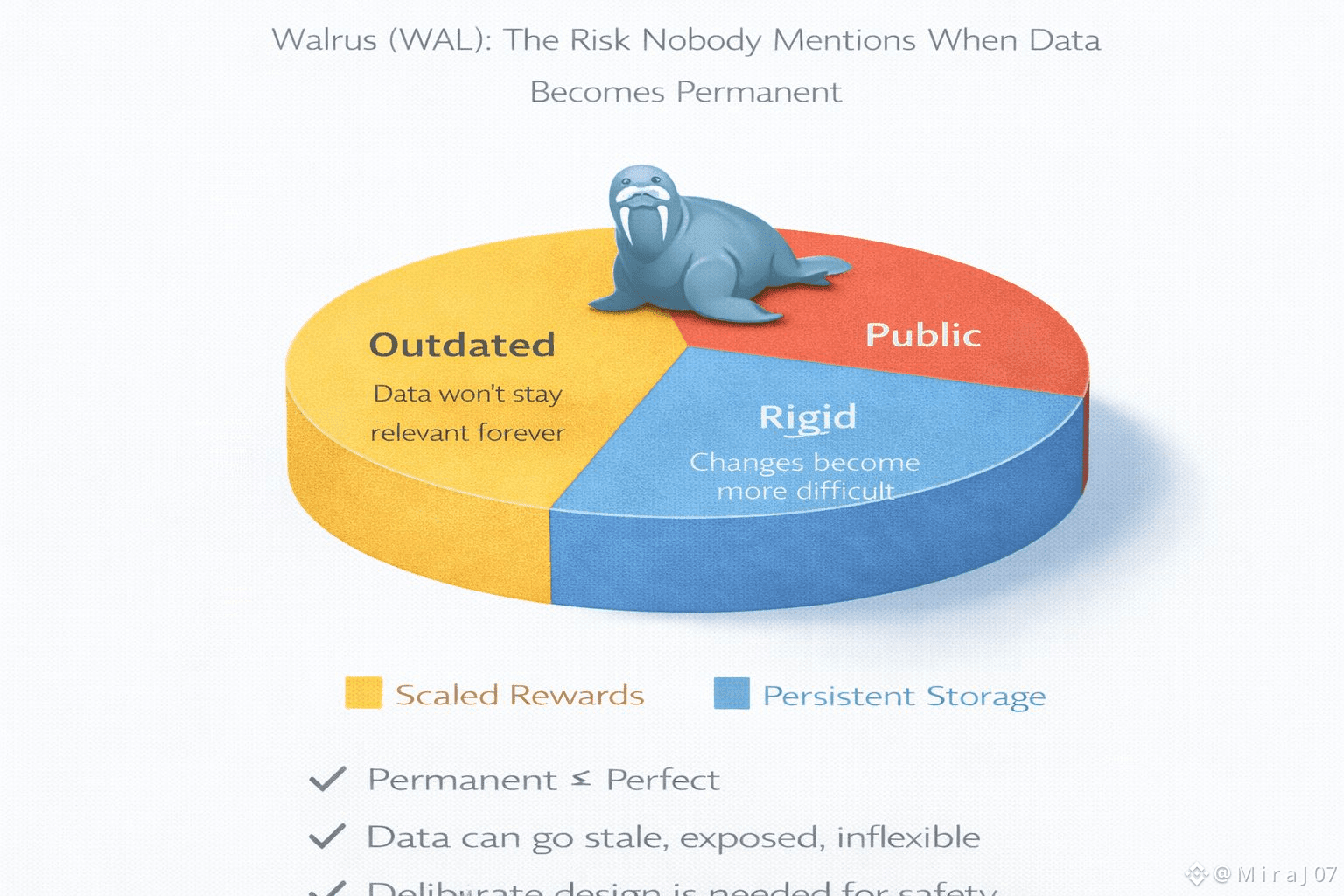

That is the risk nobody mentions when data becomes permanent and it’s the correct lens for evaluating Walrus (WAL).

Permanence changes the question from “can we store it?” to “can we live with it?”

Short-lived data can be treated casually. If it’s wrong, you replace it. If it’s outdated, you ignore it. If it’s embarrassing, you delete it.

Permanent data removes those escape routes.

When data becomes permanent, the system must answer:

What happens when this data is wrong?

What happens when it becomes evidence?

What happens when it becomes illegal in one jurisdiction?

What happens when it becomes harmful to the user who created it?

What happens when someone demands it be removed and it can’t be?

Permanence turns storage into governance.

The hidden risk is not permanence it’s permanent responsibility without a responsible party.

In centralized systems, permanence is paired with custody:

an organization owns the risk,

policies define retention,

legal frameworks assign liability.

In decentralized systems, permanence can exist without custody. That’s the danger:

data persists,

but responsibility diffuses,

accountability evaporates,

enforcement becomes unclear.

So the data is permanent, but the obligation to handle its consequences is not.

That mismatch is the real risk.

Permanent data becomes permanent evidence.

Most data is stored as information. Over time, some of it becomes evidence:

governance decisions are challenged,

financial history is audited,

provenance is questioned,

disputes demand proof.

Permanence makes evidence harder to erase but it also makes errors harder to correct. If incorrect data is stored permanently, the system must decide:

who can contest it,

how correction is recorded,

how users distinguish truth from artifact.

Permanent evidence without correction pathways creates a credibility trap.

Permanence makes “availability drift” more expensive.

When data is temporary, usability decay is tolerable. When data is permanent, usability decay becomes catastrophic.

Because permanent data is often accessed rarely until it matters most. If retrieval becomes slow, inconsistent, or expensive years later, permanence becomes a cruel illusion:

the data exists,

but it is unusable,

and it cannot be replaced.

This is why permanence demands stronger incentives, not weaker ones.

Walrus treats long-horizon usability as a core constraint.

Walrus designs permanence as a governed obligation, not a marketing claim.

Walrus does not treat permanence as “forever storage.” It treats it as:

a long-term commitment,

an enforceable responsibility,

a risk surface that grows with time.

That means designing for:

early visibility of degradation,

incentives that bind even when demand is low,

repair that remains economically rational,

accountability that doesn’t vanish into “the network.”

In this model, permanence isn’t just about keeping data alive. It’s about keeping data defensible.

As Web3 matures, permanent data becomes unavoidable.

Storage now supports:

financial proofs and settlement artifacts,

governance legitimacy and voting history,

application state and recovery snapshots,

compliance and audit trails,

AI datasets and provenance.

These datasets are valuable precisely because they persist. But their permanence also means:

they will be scrutinized later,

they will be disputed,

they will be interpreted under new rules,

they will outlive the teams that created them.

Systems that treat permanence as a simple feature are storing future liabilities.

Walrus aligns with maturity by treating permanence as a long-horizon governance problem.

I stopped celebrating permanence as an automatic good.

Because permanence without accountability is not safety it’s trapped risk.

I started asking:

Who is obligated to maintain usability years later?

Who is pressured to act when incentives weaken?

How is wrong data contested without erasing history?

What does “forever” mean when attention disappears?

Those questions define whether permanent storage is a strength or a slow-moving disaster.

Permanent data is not just hard to delete it’s hard to forgive.

When mistakes are permanent, users don’t get do-overs. When obligations are permanent, systems don’t get excuses. When evidence is permanent, disputes don’t fade.

That’s why permanence demands the strictest design discipline in Web3 infrastructure.

Walrus earns relevance by treating permanence as a liability to be governed, not a slogan to be marketed.

Permanence is only a feature when responsibility is just as permanent.