Plasma. The word hung in the air like something I should have known better, something I'd learned in high school biology and promptly forgotten because it seemed irrelevant to actual living. But watching that small wound seal itself, seeing my daughter's body knit itself back together with no conscious input from either of us, I felt the strangeness of it. Something inside her—something she'd never chosen, never controlled, never even known existed—had just saved her from bleeding out on a suburban playground.

That's when I started paying attention to plasma. Not as a concept, but as the quiet miracle it actually is.

The Conductor You'll Never Meet

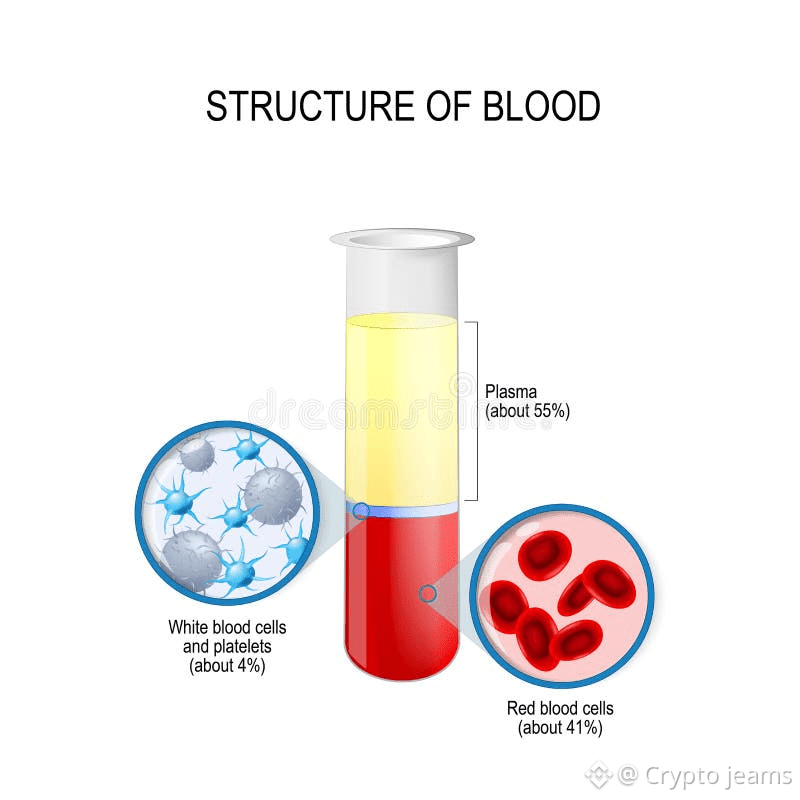

Right now, as you read this, you're conducting an orchestra you can't hear. Five liters of pale gold liquid are circulating through your body, carrying approximately 10,000 different substances to exactly where they need to be. Nutrients from your last meal. Hormones from your thyroid. Antibodies hunting for invaders. Waste products heading toward your kidneys for disposal. Messages between organs that have never directly touched.

Plasma is the conductor of this massive, silent symphony, except—and this is the strange part—there's no conductor's score. No master plan. Just trillions of molecules dissolved in water, finding their destinations through pure chemistry, like messages in bottles that somehow always reach the right shore.

Your conscious mind has nothing to do with any of this. You cannot decide to send glucose to your brain or antibodies to a cut. You cannot choose which waste products your kidneys filter out. The plasma circulating through you right now is operating on instructions written billions of years ago, refined through evolutionary trial and error that killed off every organism whose plasma didn't quite get the chemistry right.

You are alive because your plasma is conducting a symphony you'll never consciously hear. And it has been doing this, perfectly, every second since before you were born.

The Liquid Memory of Everything You've Survived

Here's something that haunts me beautifully: your plasma remembers things you've forgotten.

That chickenpox you had at age six? Your plasma still carries antibodies against it, sentinels standing watch decades later against an enemy that never returned. The food poisoning from that sketchy taco truck in college? Antibodies. The flu shot you got three years ago and barely thought about? Antibodies. Every pathogen you've ever encountered, defeated, and consciously forgotten has left permanent representatives in your plasma, ready to respond if that particular threat ever reappears.

Your immune system has been keeping a journal in your plasma since the day you were born, writing entries you'll never read in a chemical language you don't speak. It's a complete history of every battle your body has fought and won, archived in proteins floating through your bloodstream.

This means you're carrying around a molecular autobiography more detailed than your actual memories. You might not remember that cold you had in second grade, but your plasma does. You might not remember every vaccination, every infection, every microscopic invasion your body has repelled, but your plasma is a library of all of it.

There's something profound in this: the realization that you are more than what you consciously remember. Your body keeps its own history, independent of your mind, and plasma is the medium where that history lives.

The Part of You That Belongs to Everyone

My father needed plasma transfusions during his final year. Multiple myeloma had destroyed his bone marrow's ability to produce the proteins his plasma needed. His blood could no longer clot properly. His immune system couldn't manufacture antibodies. The chemical conversations his body needed to have with itself were failing, words missing from essential sentences.

So strangers gave him their words.

I sat with him during one transfusion, watching a bag of donated plasma drip into his arm. It looked like weak tea, almost boring in its ordinariness. But inside that bag were antibodies from someone who'd survived illnesses my father had never encountered. Clotting factors from a liver that worked perfectly. Albumin maintaining osmotic pressure that my father's failing body could no longer regulate.

"Four different donors," the nurse told us. "We pool it for safety and consistency."

Four people, living their normal lives, had sat in donation chairs and given away something they'd never miss. My father was receiving their accumulated immunity, their body's learned wisdom, their chemical history. For a few weeks, their plasma would flow through him, keeping him alive with borrowed proteins, secondhand antibodies, someone else's clotting factors.

The intimacy of it struck me then and hasn't left me since. We think of ourselves as discrete individuals, separate and bounded. But plasma makes liars of those boundaries. When you donate plasma, pieces of your history—the molecular record of everything you've survived—flow into strangers. When you receive it, someone else's learned immunity becomes yours.

We are more porous than we think. More connected. The same proteins that hold you together can hold someone else together. The antibodies your body manufactured against last winter's flu might save someone whose immune system can't make its own. The boundaries between us are real but permeable, and plasma is the proof.

The Thing About Thirst

I learned something embarrassing in my thirties: I'd been chronically dehydrated for years without realizing it. I thought I drank enough water. I didn't feel particularly thirsty. But the headaches I attributed to stress, the fatigue I blamed on poor sleep, the difficulty concentrating I assumed was just aging—all of it improved dramatically when I started drinking more water.

What I'd failed to understand is that plasma is 90% water, and when you're dehydrated, you're not just "low on water" in some vague sense. You're reducing the volume of the transport system that keeps every cell in your body alive.

Imagine a city where the roads start shrinking. Not closed—just narrower. Traffic still moves, but slower. Deliveries take longer. Garbage pickup falls behind. Communication gets delayed. Nothing catastrophically fails, but everything works slightly worse. The whole system degrades in ways that are hard to pinpoint because everything is connected to everything else.

That's your body on dehydration. Your plasma volume drops, which means less carrying capacity for nutrients, hormones, waste products, immune cells, clotting factors—everything. Your blood pressure decreases because there's literally less liquid to maintain pressure. Your heart rate increases to compensate. Your kidneys struggle to filter waste from a reduced volume of plasma. Your brain, which is 73% water, receives fewer nutrients and removes waste less efficiently.

All of this happens gradually enough that you don't notice the decline, only the baseline state of feeling slightly worse than you should.

The fix is absurdly simple: drink water. Boring, cheap, accessible water. Within hours, your plasma volume normalizes. The roads widen. Traffic flows. The city of your body resumes normal operations.

It's humbling, really, how much of our wellbeing depends on something so mundane.

What We Owe the River

I donate plasma now, every few weeks, at a center twenty minutes from my house. I sit in a reclining chair while a machine separates plasma from my blood cells, collects the plasma, and returns the cells. The whole process takes about an hour, during which I usually read or respond to emails or just watch the pale gold liquid flow out of me into a collection bag.

I don't do this out of altruism, exactly, though I hope it helps someone. I do it because understanding what plasma is—what it does, how it works, what it remembers, how it connects us—has changed how I think about being alive.

Every time I donate, I think about my father receiving plasma from strangers, and how those strangers saved him with something they barely noticed giving away. I think about my daughter's plasma clotting her chin wound without any instruction from her conscious mind. I think about the trillions of molecules currently dissolved in my plasma, carrying messages between parts of me that have never met, maintaining a conversation I'll never consciously hear.

Mostly, I think about how we are not the solid, separate, autonomous individuals we imagine ourselves to be. We are flows. Processes. Rivers running through temporary forms. And plasma—overlooked, underappreciated, working ceaselessly in the background—is the current that makes the river possible.

The nurse always tells me to drink extra water after donating. "Your body will regenerate the plasma in about 48 hours," she says, "but you need to give it the raw materials."

48 hours. Two days to completely replace what took years to develop, to recreate the molecular library of antibodies and proteins and chemical history that makes plasma mine and not just water with things dissolved in it.

This is the final thing plasma has taught me: that we are constantly rebuilding ourselves from borrowed materials. The water you drink becomes my plasma becomes someone else's transfusion becomes part of their history. The proteins my liver makes today might save a stranger next month. The antibodies I carry from childhood illnesses might protect someone else's child years from now.

We are not separate. We are not permanent. We are patterns maintained by constant flow, and plasma is the golden thread connecting us all.

Drink water. The river needs it. Someone downstream might need it more.