@Lorenzo Protocol If you’ve spent any time in crypto lately, you’ve probably noticed a quiet shift in what people argue about. It’s less “when moon” and more “who’s paying for this, and for how long.” That change helps explain why a halving-style cut to BANK token emissions, floated for 2026, keeps resurfacing in BanklessDAO conversations. In a softer market, inflation stops being a line in a spreadsheet and becomes a feeling. It shows up as budget anxiety, contributor turnover, and the uncomfortable realization that a token budget is not the same thing as a sustainable business model. Picking 2026 is part of the point: it’s far enough away to plan, but close enough that next season’s decisions can’t pretend it’s a “future” problem.

BANK is the governance token associated with BanklessDAO, and major trackers still anchor it to a 1 billion total supply figure. But the lived reality is messier than the “fixed supply” suggests. Circulating supply estimates vary by source, and reported day-to-day trading volume can be extremely small. When liquidity is thin, emissions don’t need to be dramatic to change behavior. A steady stream of rewards can turn into steady selling, not because people are cynical, but because rent, taxes, and time are denominated in fiat. The gap between “token compensation” and “real-world costs” is where a lot of quiet disillusionment is born.

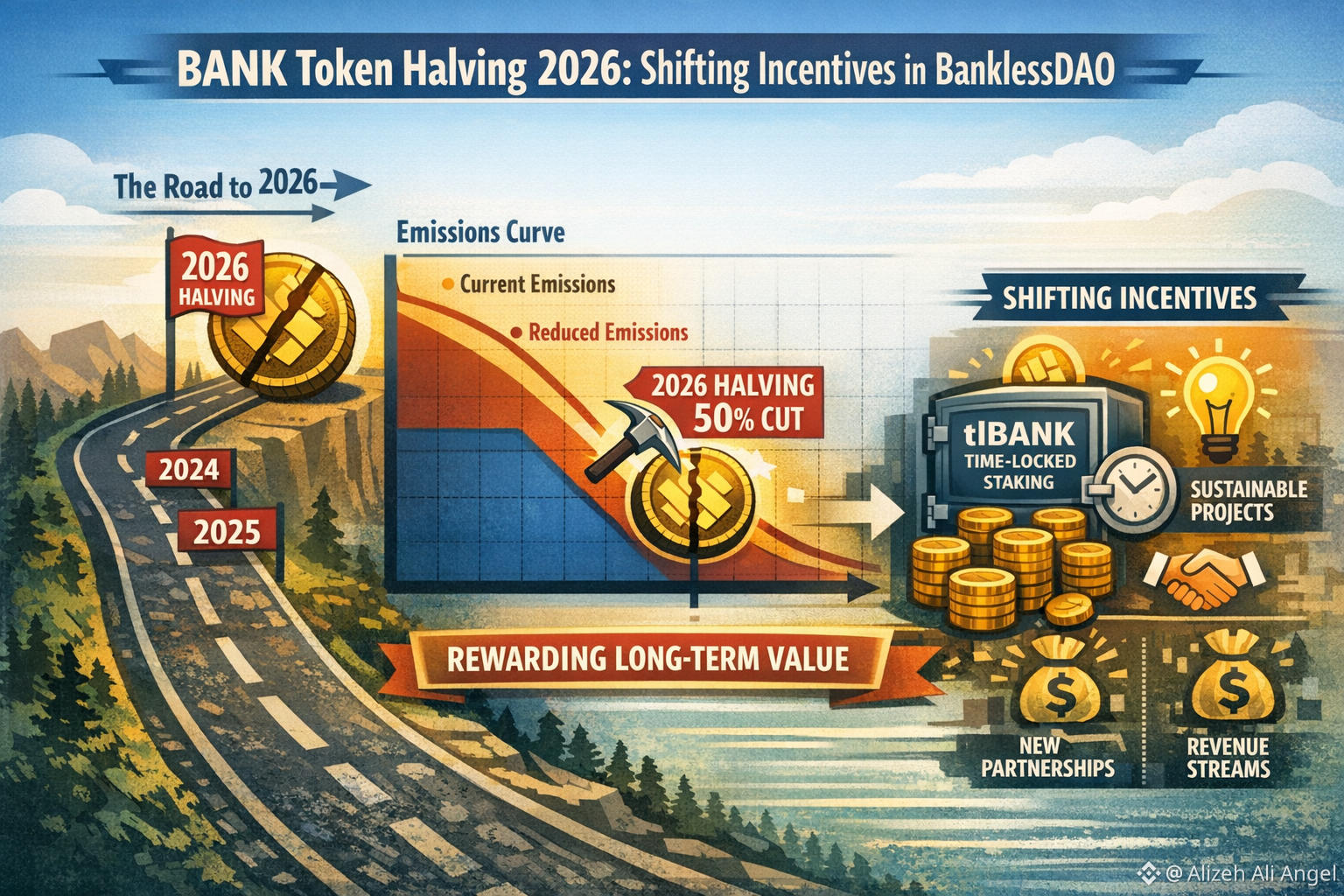

The reason “halving” is trending now is that it’s showing up beyond Bitcoin as a live experiment in incentive design. Bittensor’s TAO is entering its first halving window, with coverage noting daily emissions dropping from roughly 7,200 to 3,600 TAO. Even ecosystems without literal halving are arguing about the same tradeoff. Solana’s SIMD-228 vote, which would have reduced token emissions, failed, and reporting emphasized that emissions would remain unchanged. What’s new is not the math; it’s the cultural mood. Communities are less willing to subsidize participation forever, and more interested in whether incentives create lasting value.

BanklessDAO has its own reasons to be sensitive here. The project’s founding materials emphasized vesting, long-term alignment, and the idea that a token could coordinate a community around media and education rather than short-term speculation. In other words, BANK was supposed to be an ownership-and-governance primitive, not a faucet you leave running forever. But contributor-heavy DAOs almost inevitably drift into using emissions like payroll, because it’s the easiest lever to pull when you need momentum and you don’t want to charge people. That drift isn’t immoral; it’s just convenient, and convenience is powerful.

This is where tlBANK, the DAO’s time-locked BANK concept, becomes more than a side quest. BanklessDAO has framed tlBANK as a way to freeze liquidity, stretch out sells, and strengthen long-term value alignment across projects and contributors. The same rollup also points to real implementation work, including choosing Hedgey Finance to facilitate locking and redemption. That matters because a 2026 halving, by itself, is just a cut. Pair it with a lock-and-align tool and it becomes a re-weighting of incentives: fewer tokens in motion, but more reasons to stay, vote, and think in seasons instead of weeks.

If implemented well, a 2026 halving could force prioritization in a way that feels almost old-fashioned. With less new BANK to hand out, projects have to justify themselves in plain language. What are we building, for whom, and what changes in the world if we succeed? Scarcity nudges creativity too. DAOs start looking harder at sponsorship revenue, product pricing, partnerships, and other boring-but-real sources of income. Less dilution can be healthier for holders, but the deeper win is cultural: you stop measuring success by how many tokens were emitted, and start measuring it by what actually shipped.

But I’m wary of the “halving fixes everything” story. Emissions are not only supply; they are compensation, motivation, and sometimes the main reason a talented person keeps showing up. Cut them too aggressively and you can hollow out the contributor base that makes a DAO worth coordinating. A fixed halving date can also create a cliff dynamic: people rush to extract value before the cut, then feel punished after it. Governance can get brittle in that atmosphere, and DAOs are famously slow at reversing decisions once they’ve become identity. The token won’t automatically become “healthier” just because it becomes scarcer; the work still has to be worth doing.

The best version of this proposal is boring in the right way. It treats halving as budgeting discipline and a chance to redesign incentives around outcomes, not just participation. If BanklessDAO can use 2026 to tighten issuance while protecting the unglamorous work that compounds over years, then the mechanism could reshape incentives in the one way that matters: by rewarding what survives the market’s mood swings in practice.