In the imagination of many, once targeted by the U.S. SEC, regulatory orders are like universally applicable 'nuclear weapons': no matter where the project is registered, it ultimately has to go back to New York or Washington to 'explain the issues'. The reality is far from that simple.

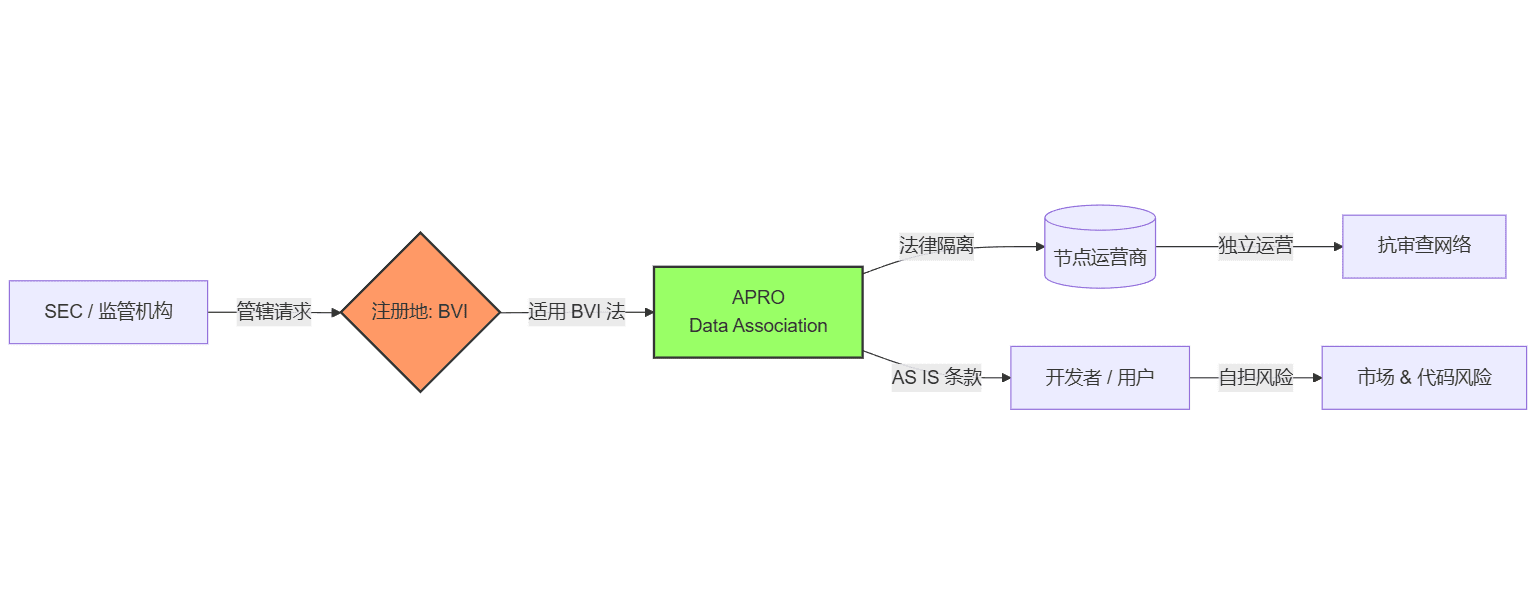

In the current regulatory environment, if a U.S. agency attempts to investigate a certain oracle or data service agreement on the grounds of 'unregistered securities', the first step often faced is not the smart contract itself, but rather the legal entity behind it and the choice of its registration location. The APRO Data Association clearly states its registered office as 'registered office at [BVI]' in its official privacy policy (docs.apro.com), and stipulates in the terms of use that the interpretation and execution of this website and related services are governed by the laws of the British Virgin Islands (BVI), with any non-arbitration disputes exclusively under the jurisdiction of BVI courts (docs.apro.com).

This means a very critical thing:

When regulators want to 'reach out', they must first cross the legal boundary of BVI in procedural terms, rather than inherently viewing APRO as a US domestic financial institution.

Under this structure, US regulators can certainly express opinions, issue inquiries, and even cooperate with other jurisdictions, but they no longer have a direct button to 'shut down' a certain agreement entity. BVI's company law and data protection framework provide a relatively clear and predictable legal environment for data-type agreements like APRO: it is defined as a technology and information service provider, rather than a traditional securities issuer or asset custodian. (Cloudwards)

From the perspective of Web3, this 'offshore safe haven' is not simply an escape from regulation, but is a layer of legal buffer actively designed under the reality of multiple legal jurisdictions:

On one hand, by using BVI's company + jurisdiction clauses, it minimizes the direct conflict risk of the agreement with any single sovereign regulation;

On the other hand, it retains the space to connect with international compliance frameworks like FATF, not locking itself in a gray area.

For developers and heavy users, this legal firewall brings a kind of 'predictability': agreements will not be suddenly shut down due to fluctuations in regulatory sentiment from a certain country, but rather have a clear set of procedures and boundaries within which they can negotiate and adjust.

1. The place of registration is itself a part of agreement design.

Traditional Web2 companies often follow a simple logic: where people are, they register their companies; where the business focus is, they obtain licenses under that regulatory framework. Web3 agreements are different—they inherently operate across countries, chains, and time zones, and the choice of registration location has become part of the architectural decision.

APRO's combination is roughly these layers:

Agreement layer: decentralized oracle network, operated by distributed nodes (node operators);

Entity layer: APRO Data Association, as the 'data and website operating entity', registered in BVI; (docs.apro.com)

Legal text layer: Terms of Use and Privacy Policy strictly limit the role to 'information service provider', emphasizing 'provided as is (AS IS), without any warranties'. (docs.apro.com)

The strategic implication of this split is:

Code and nodes operate in 'cyberspace', making it difficult to be simply directed to the jurisdiction of a certain country;

The registered entity is placed in a legal jurisdiction (BVI) that is relatively friendly to data services and foundation-type organizations, and the applicable law is written dead in BVI through governance clauses. (docs.apro.com)

Therefore, when we talk about 'APRO choosing BVI for jurisdiction arbitrage', we are not saying it hides in the shadows of the law, but rather:

It is using 'place of registration + choice of legal jurisdiction + limitation of liability' to give the agreement itself a more flexible legal shell.

2. Liability isolation: retreating from 'financial intermediary' to 'information infrastructure'.

If an oracle is legally recognized as a 'financial intermediary' (for example, performing functions such as investment advice, asset custody, and profit promises), it will naturally be drawn into the local securities, investment advisory, or custody regulatory system, bearing heavy and vague responsibilities.

APRO takes another direction:

In documentation and structure, it firmly nails itself down to the role of 'technical infrastructure / data service'.

The key point is:

The regulatory pathway first points to the BVI registered entity C, rather than all on-chain nodes D;

The terms explicitly state through 'No Warranty' and 'Limitation of Liability': the website and information are provided 'as is' and are not responsible for any investment results (docs.apro.com);

Users and developers are required to agree to the Terms of Use before using, essentially signing a legal confirmation that 'you are responsible for your own actions'.

In other words, this structure constantly emphasizes one thing:

APRO is a road, not a driver; how the road is used is the owner's choice.

3. The 'soft firewall' at the terms level: AS IS, limitation of liability, and jurisdiction clauses.

If you take a closer look at APRO's Terms of Use and Privacy Policy, you'll find three very 'lawyerly' designs: (docs.apro.com)

AS IS statement

The website and services do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, merchantability, or suitability for a particular purpose;

All content is subject to change at any time, and the parties to the agreement are not responsible for losses caused by the use of information.

Limitation of Liability

Even if losses occur, the liability of APRO and its affiliates is limited to a very narrow range of amounts;

Liability for indirect losses, profit losses, data losses, and other broad types of damages is exempted or limited.

Governing Law and Jurisdiction

It is explicitly stated: these terms and disputes related to the website/services are governed by BVI law;

Non-arbitration disputes are exclusively under the jurisdiction of BVI courts, and users waive objections to that jurisdiction. (docs.apro.com)

These three pieces combine to form a 'soft firewall':

No commitment to 'profits' → reducing the risk of being treated as a securities issuer or investment advisor.

Limiting the scope of liability → even if disputes occur, it reduces compensation expectations.

Locking in applicable laws and courts → avoiding being forcibly drawn into other jurisdictions.

For the agreement, it is like adding several layers of 'fire barriers' in the real world, preventing potential legal fires from directly burning the core business.

4. The institutional advantages of BVI itself: a triple space of privacy, data, and finance.

BVI has long been viewed as an 'offshore financial center', not just because of the tax environment, but also due to its relatively stable and clear attitude towards entity establishment, privacy protection, and cross-border business.

The Data Protection Act, which came into effect in 2021, largely references the GDPR framework:

Emphasizing the legality, fairness, and transparency of personal data processing;

Requiring data controllers to take reasonable technical and organizational measures to protect privacy;

Applicable to businesses established in BVI but handling global user data. (Cloudwards)

For data service-type agreements like APRO, there are several practical benefits:

It can operate its privacy policy under a mature legal framework, rather than being in a completely 'extralegal' state;

At the same time, it avoids the high-intensity penetrating regulation of 'financial activities' in places like the US and EU—because APRO is a 'data and technology service provider' at the legal level, rather than a licensed financial institution.

This combination of 'privacy under the law, business not overly characterized' is very suitable for oracle, data feeding, indexing services, and other infrastructure-type agreements.

5. Comparison with the 'US local registration + geographical blocking' path.

Some competing agreements have chosen another path:

In US local registered entities;

Accepting direct constraints of local securities and financial regulatory frameworks;

Under pressure, saying 'no' to users in certain regions through geographical blocking (Geo-blocking).

The advantage of this path is:

It connects more closely with the US compliance system, facilitating cooperation with traditional institutions;

But the drawbacks are also very obvious:

The network is artificially 'sliced', and agreements present different forms in different regions;

Once the regulatory stance shifts sharply, the agreement may be forced to go offline or be revised quickly.

APRO's model of 'BVI + distributed nodes + B2D (for developers)' tries to avoid letting the entire network be 'locked down' by an administrative decision from a single country.

It directs more of the 'pressure from the physical world' toward a relatively neutral entity defined within the BVI legal jurisdiction—Data Association; while leaving the 'responsibilities of the code world' to nodes, contracts, and developers themselves.

This does not mean it can ignore regulation, but rather means:

It has secured a buffer period of 'negotiation space and time window' for itself.

6. Insights for participants: the legal framework is part of the agreement's security.

Many people evaluate a Web3 agreement by only looking at these:

Does the contract have an audit?

Does the oracle have a backup?

Is the node decentralized?

But cases like APRO remind us:

The legal framework is also a component of the agreement's 'security'.

Smart contract layer: protection against hackers, vulnerabilities, and economic attacks;

Legal framework layer: protection against subpoenas, forced delisting, and single-point regulatory risks.

BVI registration location, AS IS in Terms of Use, limitation of liability, and Governing Law—these seemingly 'boring legal footnotes' actually answer one question:

When the forces of the real world knock, can this agreement respond in an orderly manner rather than collapse instantly?

For developers, this means:

Consider security when writing contracts, and take legal jurisdiction into account when designing architecture;

For heavy users or investors, this means:

When looking at an agreement, in addition to the code and TVL, also consider which legal coordinate system it has placed itself in.

In the future, as regulation becomes increasingly detailed,

Only those agreements that have done architectural design in both the 'code layer' and 'legal layer' will have the opportunity to become truly long-term infrastructure, rather than short-lived speculative stages.

I am a boatmaker seeking a sword, an analyst who only looks at essence and does not chase noise. @APRO Oracle #APRO $AT