Author: Bennett Ma

In the face of the complexity of smart contract applications, we should abandon the simplistic thinking of 'code is law' and instead adopt a more nuanced and pragmatic perspective of 'scenario analysis.' Only in this way can we clearly define rights and responsibilities and manage benefits and risks while embracing technological innovation.

Introduction

The concept of 'Smart Contract' was initially described merely as a digital protocol capable of executing automatically. However, when the concept was implemented in practice, people found that this code, which could run automatically, could serve not only as a 'contract' but also as rules for organizational governance, a channel for asset transfer, and even a tool for illegal activities.

Although smart contracts are not used as "contracts" in many scenarios, they are generally referred to as "smart contracts." This shows that "smart contract" is not a legal concept, but rather a technological concept with different application scenarios. Different scenarios correspond to different social relationships, and these social relationships, once confirmed by law, become legal relationships. Even slight differences in the scenario can lead to different social and legal relationships.

Based on this, this article aims to explore the legal characterization of smart contracts in different application scenarios. Although it is difficult to cover all situations, it still hopes to help readers gain a simple understanding of the relevant legal issues.

Why is it necessary to clarify the legal characterization of smart contracts? — Characterization determines fate.

To understand the importance of clarifying the legal nature of smart contracts, nothing is more important than examining real-world legal conflicts.

Tornado Cash is a decentralized, non-custodial mixing protocol deployed on Ethereum. At its core is a series of immutable smart contracts that allow users to deposit cryptocurrencies into "pools" built from these contracts for mixing, thereby concealing the source and flow of transactions.

Because the agreement has been used to launder more than $7 billion since its creation in 2019, in August 2022, the U.S. Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), pursuant to an executive order, added Tornado Cash to its sanctions list. A key point to note is that the executive order stipulates that the sanctions must target "property" owned or controlled by a "legal entity."

In addition, in August 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice also filed criminal charges against the co-founders of Tornado Cash, accusing them of conspiracy to launder money, conspiracy to violate sanctions, and conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transfer business.

These two actions address several key legal disputes:

Is a "smart contract" itself a legal "entity," or "property," or simply a "contract" or "code"?

Are "smart contracts" and the huge pools of funds they manage considered "property" that can be sanctioned?

In terms of criminal liability, what should "smart contracts" be considered, and how will their legal nature affect the legal liability of the founders?

turn out:

Regarding sanctions, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in November 2024 that OFAC's sanctions exceeded its authority. The court's core argument was that "smart contracts" are merely "neutral, autonomous technological tools" rather than legal entities, and these "immutable smart contracts" cannot be owned or controlled by any individual or entity, nor can anyone prevent others from using them. Therefore, they do not meet the traditional legal definition of "property," and OFAC had no right to include them in its sanctions.

However, regarding developer responsibility, the technological victory does not mean developers can rest easy. Smart contracts are considered "a core tool and component of an unlicensed money transfer service," and smart contracts, along with the developers' actions, are classified as "the operation of an illegal financial business." Therefore, in a criminal trial at the end of 2024, founder Roman Storm was convicted of "operating an unlicensed money transfer business."

The Tornado Cash case clearly demonstrates that the legal characterization of smart contracts can directly determine the course of a case and the fate of the parties involved. The code itself may be neutral, but those who create and deploy the code, and the parties involved, may be held responsible for its actual impact and consequences.

This suggests that carefully assessing the legal nature of "smart contracts" in light of specific scenarios is no longer an option, but a necessary requirement for maintaining transaction security and identifying legal risks.

The legal nature of smart contracts – the scenario determines the nature.

The legal nature of smart contracts depends on the specific scenarios in which they are deployed and operated.

Different scenarios reflect or construct different social relationships, and the law evaluates them differently, thus corresponding to different rights, obligations and responsibilities.

Below, I will demonstrate some typical application scenarios:

(a) The legal nature of smart contracts when used to construct contracts

When discussing the legal nature of smart contracts, the most frequently asked questions are: Can they be legally recognized and enforced? Do they possess the legal force of a contract?

When the word "contract" is mentioned, many people first think of "agreement." Indeed, using smart contracts to trade digital collectibles is an agreement; using them to participate in voting decisions of decentralized autonomous organizations is also an agreement. However, not all "agreements" can constitute a "contract" in a legal sense.

"Consensus" is a relatively broad concept, similar in meaning to "agreement," but neither of them can be directly equated with "contract." From a legal perspective, a contract is a subordinate concept to "consensus" or "agreement." The core characteristic of a contract is that it has the guarantee of legal enforceability. Although a resolution is also a product of consensus, the law often only "confirms" its procedural validity and does not necessarily grant it the guarantee of compulsory enforcement.

In simple terms, we can use a concise framework to determine whether a smart contract constitutes a "contract": Contract = Consent + Legality

Consensus refers to the agreement of the parties involved, and usually requires two or more parties. The execution of smart contracts often reflects a pre-defined common intention.

Legality has two meanings:

The law recognizes such agreements as contracts: not all agreements are considered contracts. For example, internal decisions executed using smart contracts are generally not classified as contracts, but rather as organizational governance actions.

The agreed-upon content must not violate laws and regulations: this includes not infringing on specific prohibitions (such as money laundering, fraud, concealment of crimes, or financial regulatory policies), nor violating legal principles such as public order and good morals. The former is relatively clear to determine, while the latter requires specific analysis in conjunction with judicial practice and regional legal culture.

This framework can help us make an initial judgment on whether a specific smart contract application can be identified as a contract, and the source of its enforceability, when facing a specific smart contract application.

For example, we can apply this determination method to analyze the following situations:

Situations that may constitute a contract:

If both parties enter into a digital collectibles sales contract through digital signatures, and the contract is legally valid and reflects their true intentions, then the contract is legally binding.

If new terms are added to an existing written contract in the form of a smart contract, and such terms are legal in themselves, they can be considered part of the contract.

If a smart contract is used merely as a tool to fulfill existing contractual obligations, and it still embodies mutual agreement and is legal in content, it may also be considered a contract (if it conflicts with a written contract, the issue of priority of validity needs to be determined separately).

Situations that do not constitute a contract:

Money laundering using a coin mixer by a single person does not constitute "consensus" because there is no counterparty involved.

If the two parties use smart contracts to conduct virtual currency transactions, and these transactions are used for illegal activities such as money laundering or gambling, the contracts will not be valid due to the illegality of the content.

In a DAO, governance actions such as voting and profit distribution are executed through smart contracts. Such agreements are usually recognized as internal organizational decisions rather than contracts.

It is important to note that the legality of smart contracts and the legality of the virtual currencies involved are two different issues. Even if virtual currencies are recognized as having property attributes, smart contracts may still be deemed invalid if they violate public order and good morals or financial regulations.

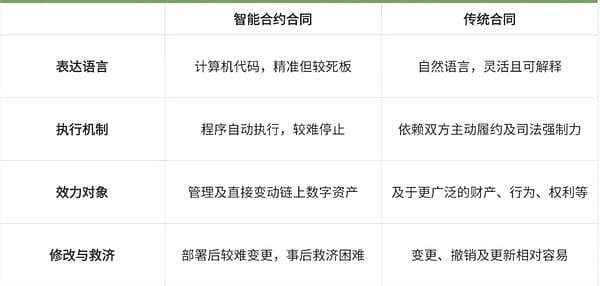

Furthermore, although some smart contracts can be classified as contracts, they still possess a number of characteristics that differ from traditional contracts, such as:

These characteristics profoundly affect the rights, risks, and remedies of the parties involved.

Taking the risk burden when smart contracts have technical flaws as an example, its determination requires a layered consideration:

For both parties to the contract, risk allocation requires a comprehensive review of multiple factors, including the specific design of the contract terms, the execution mechanism of the smart contract, the parties' understanding of the relevant technologies, the depth of their participation in the process, and the due diligence obligations they should fulfill.

For programmers, the key to determining liability usually lies in whether the service was provided for a fee:

If the code writer acts as a third party providing paid services, their legal status is analogous to that of a product provider, and they are liable for code defects. However, whether the scope of liability should be limited to the service fee or extended to the transaction price involved in the contract is currently unclear and lacks a unified standard in judicial practice.

If the code originates from an open-source project or is provided free of charge, the likelihood of the writer bearing legal responsibility is relatively low.

(II) The legal nature of smart contracts when used to build decentralized autonomous organizations

Smart contracts are widely used in decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), and their role is mainly reflected in three aspects:

1. Define organizational rules—agree on governance mechanisms, member rights and responsibilities, and decision-making processes;

2. Forming collective decisions—gathering the will of members and making specific decisions;

3. Ensure automatic execution – implement rules and decisions through code.

From a legal perspective, different functions correspond to different legal natures:

If the contract is primarily used to define organizational rules, it may be regarded as an organizational charter, partnership agreement, or self-governing regulation, and its specific characterization depends on the content of the contract itself, which in turn shapes the legal attributes of the DAO.

If a contract is used to form a collective decision, it is usually considered a decision-making act and is binding on the organization and relevant participating members.

If a contract is merely used as a tool for automatic execution, it may not possess independent legal attributes and is instead considered a technical means of fulfilling organizational functions. Even so, it will still be subject to laws, regulations, or internal organizational agreements. For example, it may need to maintain consistency with existing bylaws, disclose relevant functions, and be subject to liability for errors in execution, potentially resulting in developers or members being held responsible.

In practice, the same smart contract may serve one or more functions, and its specific characterization should be determined by combining the actual functions and usage scenarios.

(III) The legal nature of smart contracts when used for illegal operations such as money laundering

The application of smart contracts in illegal and criminal activities is not uncommon, with various complex models emerging in the money laundering field alone. In such cases, the core controversy often lies not in the legal nature of the smart contract itself, but in the fact that if it is used for illegal purposes, the relevant developers, users, and even node participants may face criminal liability or administrative penalties.

Taking the Tornado Cash case mentioned earlier as an example: Although the U.S. Treasury Department's sanctions have been declared invalid, its developer, Roman Storm, is still embroiled in legal disputes. Storm is charged with three counts: conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transfer business, conspiracy to launder money, and conspiracy to violate U.S. sanctions against North Korea. On August 6, 2025, a jury in the Manhattan Federal Court in New York found him guilty of "conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transfer business," which carries a maximum sentence of five years in prison.

Although the post-trial motions filed by Storm's defense lawyers and prosecutors are still pending, this case has clearly demonstrated that, given the still ambiguous legal nature of smart contracts, judicial practice places far more demands on code developers than simply "maintaining technological neutrality" or "avoiding becoming the actual controller."

(iv) Smart contracts as objects of intellectual property protection

In today's society, it is a general consensus that intellectual property rights are protected by law. However, practitioners still need to conduct specific analyses based on the form of the smart contract, its innovative content, and the intent of protection to determine whether the smart contract is protected by intellectual property rights and what kind of intellectual property rights it can be protected under (such as copyright, patent, trade secret).

1. The "Text" and Copyright of Smart Contracts

For most programmers, writing smart contract code is mainly to achieve a certain function, and they may not be pursuing groundbreaking innovations, but this does not mean that their intellectual property cannot be protected.

Copyright provides a protection path for smart contracts. Although the term "work" may easily evoke images of books, paintings, etc., it actually protects the expression of intellectual achievements that meet the requirements of a "work," rather than the underlying technical ideas or functional logic, and does not have special requirements on the "technical" level of the code.

Therefore, if the code representation of a smart contract satisfies the requirements of originality, intellectual property, and tangible representation, it may be classified as a "work" and protected by copyright.

Originality: The code is created independently by the developer, reflecting their personalized choices, arrangement, and expression, rather than a simple copy of public domain code or general functionality.

Intellectual: Code is the result of developers using professional knowledge and logical thinking to design and write code. It is a direct product of intellectual activity, rather than a mechanical or purely functional arrangement.

Tangible representation: Code is fixed in textual form and can be perceived, copied, and disseminated. It is important to note that copyright protection is limited to the textual expression of the code itself and does not extend to the technical solutions, algorithmic ideas, or functional logic it embodies.

If a smart contract is recognized as a work under copyright law, the rights holder automatically enjoys a series of moral and economic rights over its code text, including the right of publication, the right of attribution, the right of modification, the right of reproduction, and the right of communication to the public via information networks.

Copyright is automatically generated when a work is completed. Although it does not require administrative registration to take effect, registering copyright or using reliable timestamps or other technical means of evidence can effectively strengthen the proof of ownership in the event of a dispute.

2. The "Technology" and Patents of Smart Contracts

If a smart contract not only contains code but also implements a technological solution with innovative value, it may be classified as a "patent" and can be protected by applying for patent rights.

Unlike copyright, which arises automatically, patent rights require application, examination, and authorization to be obtained. A smart contract's technical solution has the basis for patent application if it simultaneously meets the following three criteria:

Novelty: This technical solution is not existing technology and has not been publicly disclosed or used.

Creativity: Compared with existing technologies, this solution has outstanding substantive features and significant progress.

Practicality: It can be manufactured or used and can produce positive technical effects.

Patents are divided into three categories: invention, utility model, and design, each with different scopes of protection and application strategies. The core of the patent system lies in "disclosure in exchange for protection," meaning that applicants fully disclose their technical content to the public in exchange for exclusive rights to implement the technology for a certain period. This implies more difficult technology disclosure and a more rigorous examination process, but it may also result in a longer protection period and stronger commercial exclusivity.

Whether to apply for a patent for smart contract-related technologies requires a comprehensive assessment of factors such as the technology lifecycle, market competition, and trade secret protection. Given the highly specialized nature of patent applications, the complexity of the process, and their far-reaching impact, it is generally recommended that patent attorneys assist with the planning and execution of the process.

3. The "Information" and Trade Secrets of Smart Contracts

If the technical solutions or business information in a smart contract do not meet the protection conditions of patents or copyrights, or if the developer is unwilling to disclose its content, then it may be considered whether it falls under the category of "trade secrets".

A contract may be classified as a "trade secret" and protected as such if it meets the following criteria.

Confidentiality: The information is not disclosed or is not easily legally obtained by others.

Value: It can bring real or potential competitive advantages or economic benefits to the holder.

Confidentiality measures: The rights holder has adopted reasonable and continuous confidentiality measures, such as access control, encrypted storage, and signing confidentiality agreements.

The scope of protected trade secrets is broad, including technical and business information that is not publicly known, has commercial value, and for which the rights holder has taken appropriate confidentiality measures. Core algorithms, unique architectures, business logic, or undisclosed parameters in smart contracts can all be included in the category of trade secrets.

Protecting trade secrets does not rely on registration or review. The main legal means is to sign confidentiality agreements with internal employees, partners, etc., to restrict them from disclosing, using, or allowing others to use relevant information. Although this method does not require the technology to be disclosed, it relies heavily on continuous internal management and compliance supervision to maintain the confidentiality of information.

(v) The legal nature of smart contracts in litigation

Smart contracts, due to their transparent and immutable technical characteristics, are often regarded as an ideal form of electronic evidence. However, in legal practice, using them as evidence is more complex than traditional forms of evidence. This complexity mainly stems from the following technical characteristics:

1. Smart contracts are written in code. On the one hand, the professionalism and complexity of code significantly increase the cost of understanding and argumentation in litigation, requiring public authorities and parties to invest more resources in interpretation. On the other hand, code cannot fully and clearly express the true intentions of the parties as naturally as natural language, and the parties may also reach an agreement outside the contract. Therefore, smart contracts often cannot be used as the sole basis for a judgment and need to be corroborated by other evidence.

2. Smart contracts offer anonymity. In many cases, the identity of the entity operating through a smart contract is difficult to trace directly. Although powerful public authorities can overcome anonymity barriers through technological means in major criminal cases such as money laundering, identity verification remains a significant challenge in numerous civil or non-criminal disputes.

3. Smart contracts operate on a decentralized architecture. Their execution does not rely on real-time control from a single center, making it difficult to determine the responsible party in case of disputes—multiple parties, such as code writers, deployers, and node participants, may be involved, but there are no clear legal rules to delineate their responsibilities.

Therefore, although the evidentiary value of smart contracts has not been denied in law, and the issues of burden of proof allocation involved are still within the framework of traditional evidence rules, the special nature of their technical language and operating mechanism does indeed place higher professional demands on parties, judicial organs, and relevant professionals in judicial practice regarding the review and determination of smart contracts.

Compliance advice for participants

Given the complexity of the legal nature of smart contracts, we can at least do the following:

Be bold in protecting your rights and proactively comply with regulations: Industry development drives social change and inevitably generates many new legal issues. Whether it's a risk or an opportunity, practitioners must be proactive.

Clearly define the scenario and make precise definitions: In legal practice, especially in some important legal documents, the term "smart contract" should be avoided in general terms. Instead, the concept should be explained when necessary.

When used in transactions, comprehensive attention should be paid to legality, technical details, and remedies: both parties should at least pay attention to whether the transaction scenario is legal, as well as the security audit of the code, whether it accurately reflects the true intent, and the remedial measures and allocation of responsibilities in case of disputes afterward.

When used for specific functions, it is essential to consult relevant laws and regulations: Smart contracts have a wide range of applications, which may involve completely different branches of law. Especially when used in specific fields such as DAOs, finance, and asset issuance, it is crucial to check whether there are any special laws and regulations in that field or specific region to ensure proactive compliance.

Pay attention to jurisdiction and applicable law: Smart contracts are inherently transnational, but laws are territorial. Even disputes involving the same smart contract may be governed by different regulations in different regions. Considering these issues from the initial project design stage can greatly help reduce legal disputes. For example, participants can agree in advance on the applicable law and the court or arbitration institution with jurisdiction in the event of a dispute, thus clarifying transnational legal risks.

Conclusion

Real-world applications and legal practices are far more complex than what this article presents. Therefore, the author does not aim to "clarify" the relevant legal issues through this article, but rather hopes to popularize relevant legal knowledge and convey the following concepts:

Faced with the complexity of smart contract applications, we should abandon the simplistic thinking of "code is law" and instead adopt a more refined and pragmatic perspective of "scenario-based analysis." Only in this way can we clearly define rights and responsibilities, and manage benefits and risks while embracing technological innovation.